Sundaram Climate Institute (P) Limited

In the Press

2019

Volatility, thy name is onion: A deep-dive into water, markets and the great Indian onion story

Delhi air pollution crisis: Money, political will, clear data or steadfast public attention — what really matters?

Lok Sabha Election 2019: Compelling local narrative, targeted income scheme could make water a voting issue

Author Mridula Ramesh On How Climate Change Is Fatal for Women... Read More

Lok Sabha Election 2019: Voting on Delhi’s water crisis — the matter of time and scale

Why do voters care about provision over management of a resource like water? That was the question... Read More

Author Mridula Ramesh On How Climate Change Is Fatal for Women

Author Mridula Ramesh On How Climate Change Is Fatal for Women... Read More

Indus waters: For both India and Pakistan, the choice is between provision vs management

In our previous column, we saw how the Indus Waters Treaty... Read More

Lok Sabha Election 2019: What polls in India have to do with winning the country's water crisis

Many urbans Indians have far too little water — just over two buckets a day to drink, bathe, cook ... Read More

Indus Waters Treaty: Partition to Cold War and drought, how India lost hydro disciplining tool against Pak

What might have been had India not been partitioned? Had Jinnah not died? Had China not taken over Tibet? Read More

How the British transformed, subjugated the Punjab through canals — and left it vulnerable to external shocks

The British transformation of the Punjab — disruption and imbalance Read More

Amid calls for Indus' geopolitical weaponising, a reminder of how climate change has affected the river in the past

ecently, there has been a bit of a bother that Delhi is at the epicentre of a growing groundwater crisis. Like any bother... Read More

Interview with Mridula Ramesh

Mridula Ramesh is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, an organisation focused... Read More

World Water Day: When Will We Wake Up to the Groundwater Crisis?

Will Groundwater Crisis Become an Election Issue When We Run Out?

ecently, there has been a bit of a bother that Delhi is at the epicentre of a growing groundwater crisis. Like any bother... Read More

Marrying climate change and financial sustainability: The curious and troubling case of coal in India - II

Coal via the largesse that coal mining creates for special interests ... Read More

ZEE JLF 2019: Green Cause - Let’s talk climate

Described as the ‘greatest literary show on Earth’, the ZEE Jaipur Literature Festival ... Read More

With massive footfalls, stellar conversations, the ZEE Jaipur Literature Festival 2019 ends on a high note of substance and bonhomie #ZEEJLF

Jaipur: The twelfth edition of the ZEE Jaipur Literature Festival,the world’s largest literary ... Read More

12th Jaipur Literature Festival: Climate fiction rules the festival, as books on black holes, killer robots predict dystopian future

It is 2098. In China, Tao is handpainting pollen on to some fruit trees. Read More

Data, democracy and decision making: A look at climate change and India through the prism of past, present, future

#1: The world has warmed by about 1°C in the past century Read More

"Volatility, thy name is onion: A deep-dive into water, markets and the great Indian onion story"

Published : Dec 16,2019

At the heart of India's onion problem is the misalignment of risk and reward. In well-functioning financial markets, he/she who takes the greater risk, gets the greater reward. In onions, that is broken. The farmer takes the risk — of climate, of water, of market — yet shares very little of the reward.

-Indians consume onions every day: in curries, in salads, as accompaniments. Meaning, there is year-round demand.

-Supply, however, is seasonal.

-Onions come from primarily from three states (Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka) who, between them, provide two-thirds of the onion crop.

By the time you read this, a kg of onions may be selling at just Rs 80 to 100, as farmers take their not-fully-ripe crop into markets to take advantage of high prices. On 10 December this year, that same kg sold for Rs 250 in Chittoor in Andhra Pradesh and Madurai in Tamil Nadu. An article from The Hindu says,

‘The price of the third grade variety, which is on the verge of rotting, touched the Rs 200-mark.’

Rs 200 for a kg of almost-rotten onions — wow! Last year, around this time, the same kg sold for just a rupee at one of the main wholesale markets of India.

Seasonality

The problem begins with seasonality. Indians consume onions every day — in curries, in salads, as accompaniments. Meaning, there is year-round demand.

Supply, however, is seasonal. Onions come from primarily from three states — Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Karnataka — who, between them, provide two-thirds of India’s onion crop. Most of Maharashtra, the largest supplier of onions, follows the rabi, or winter, cycle for onions, where the harvests begin to hit the markets in April. Madhya Pradesh’s crop follows the same pattern. But wily Madhya Pradesh farmers are beginning to shift their crop to the kharif season where rainfall permits, to take advantage of higher prices in October and November.

Predictably, prices in India begin to crash in mid-March ahead of arrivals, and begin to rise again as storage is exhausted — stock either sold or rotten. Prices peak post-monsoon and fall when and if Karnataka’s kharif (summer) onions come to the rescue in December/January (see Figure 1).

So, why the crisis this year?

Poor prices. 2018.

In 2018, in the key onion growing markets of Lasalgaon, Pimpalgaon, and Solarpur, onion prices in September to November in 2018 were the lowest in five years. In December 2018, wholesale market prices at Lasalgaon, hit just Rs 1 per kg. This is when farmers decide which crop to sow. When growing onions costs about Rs 9-10 per kg, not growing onions was a no-brainer. Onion acreage in the winter season thus probably came down substantially as farmers planted a smaller rabi crop. Now, this rabi crop is stored from April to November, when the first onions from the summer crop begin to arrive in the markets. If all goes well, that is.

Weather anomalies. 2019.

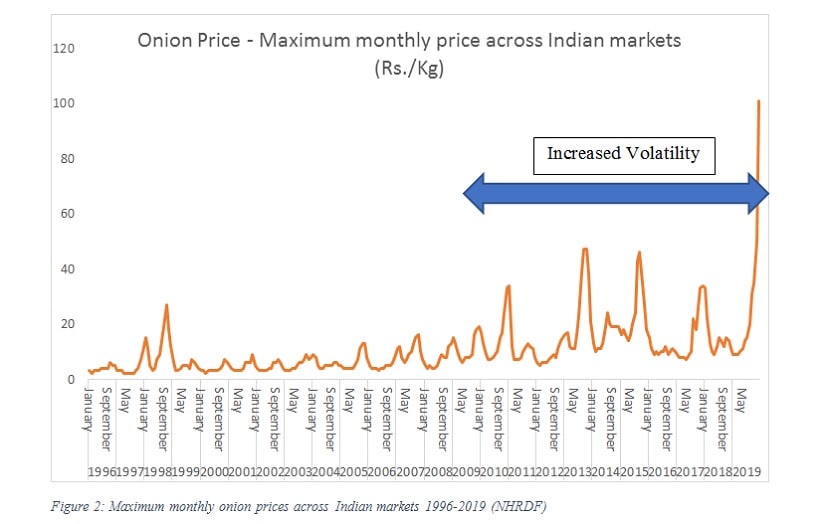

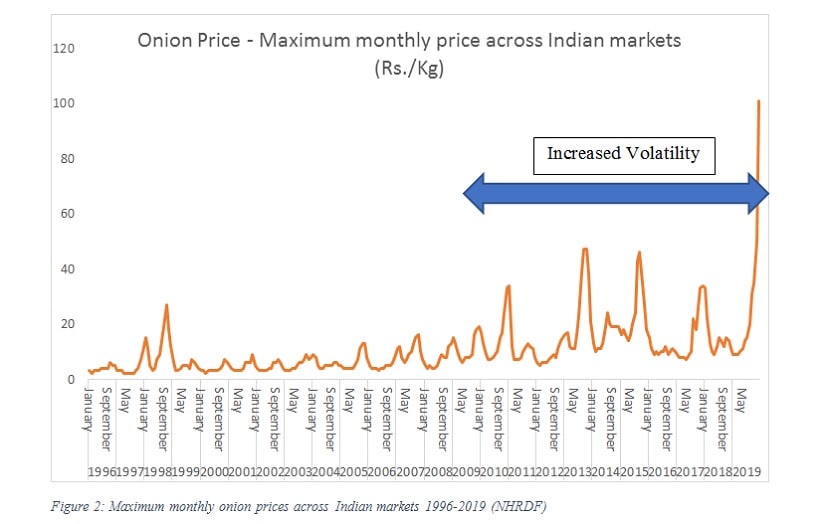

But things didn't go well. Consider the price of onions over the past two decades:

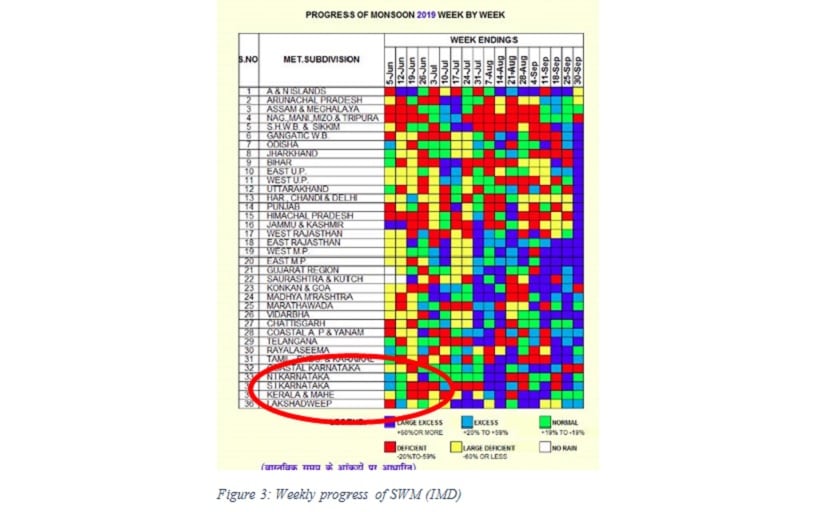

The increased volatility of this decade owes much to water — too much or too little. Onion farmers tend to be small, often managing less than two hectares. This is an important fact to keep in mind while solutioning. Small farmers tend to have low clout in local markets, get their credit from informal sources and do not have access to the best seeds, irrigation or growing practices. Which means, if rains come late, as they did this summer monsoon, these farmers do not have access to drip irrigation which would have protected them from such vagaries of the weather. Instead, these farmers delayed their sowing. This happened in some of the key summer growing districts of Karnataka this year (see Figure 2), which meant the needed price relief in November did not come.

But the biggest blow came from flooding. The onion has a shallow root system and the crop is highly sensitive to flooding. The heavy rains and consequent flooding this year in key districts of Maharashtra and Karnataka, just as the onion crop was near to harvest sent prices upwards. By some accounts, a third of Maharashtra’s cultivated land fell prey to unseasonal flooding. A part of the stored winter onions fell prey to the rising waters or the damp as well, further lowering sellable stock.

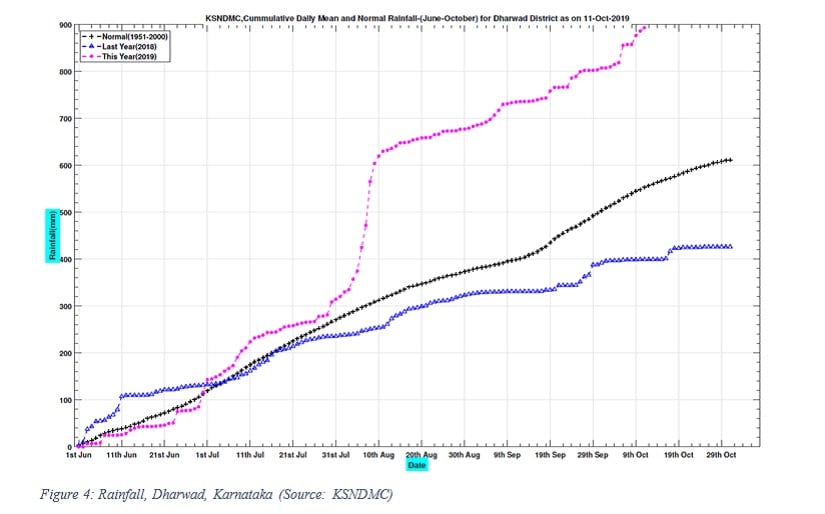

Consider the rainfall graph of Dharwad, an important district for summer onions in Karnataka. The abnormal rain in September and October probably lowered yields substantially. Constant rain and flooding makes harvest and transport of a perishable crop harder, putting an upward pressure on prices. As the climate warms, one of the more robust predictions is the rise of extreme events — high intensity rainfall — which often leads to flooding. Meaning this pattern is one we should prepare for.

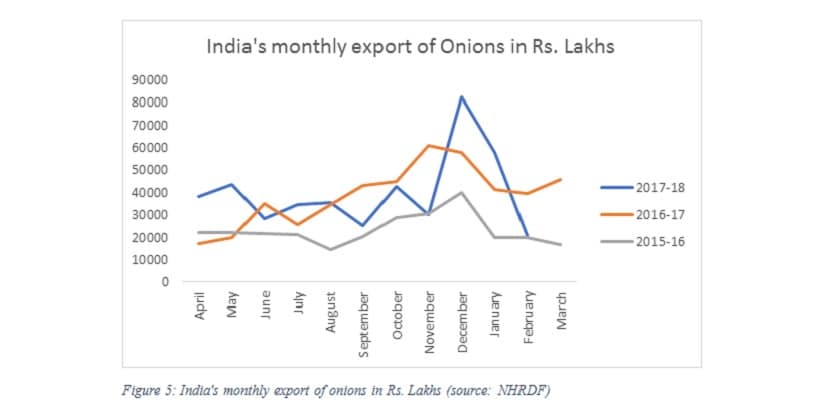

However, as prices rise, it’s a good time to trade. India exports about 7 percent of its crop, mainly in the months of November/December as the gap between rabi-storage and kharif-arrival wedges up prices (see Figure 4).

India is the second largest producer of onions in the world, producing nearly a quarter of the world’s crop. It’s also amongst the least productive, with a yield just 1/4th of America’s yield, and a fifth less than China. If India’s yields rose, and water-issues managed, farmers would be burning their crops because prices would be too low. So, our enemy, if you will, is volatility. That is what needs to be addressed.

How?

Intervene early

As a spinning mill, we buy cotton, which accounts for half our selling price. As such, understanding cotton crop development across the world from sowing intentions to harvest conditions is critical. There are several services available today for this. For a crop as important as onions are purported to be, it’s shameful that we do not have a transparent equivalent. Today, technologies such as drones, and the ubiquitous presence of mobile phones make it child’s play to understand farmer’s sowing intentions for the rabi and kharif crops, as well as early crop development. This will make it easy to book necessary imports or exports ahead of time and lessen volatility.

Better water management

Volatile water is a defining feature of climate change. It’s going to get worse, so we need figure out how to manage it better.

Too little: Adoption of drip irrigation can make short work of delayed rainfall. But drips require both a standing source of water, which is the stuff of dreams for the small onion-growing farmers. Besides, drips are expensive (thought subsidised), require labour and expertise to maintain, all of which are hard for small farmers. However, perhaps growing summer onions in places where a standing source of water (even groundwater) is a possibility that has been talked about — Punjab is one potential candidate. Onions take up far less water than paddy.

Too much: Flooding may well become a fact of onion-life. Planting on broad bed furrow (BBF) instead of traditional flat beds may reduce losses from flooding in kharif season. Greenhouses may help shield the crop from intense rainfall. “Today, greenhouses are too expensive for an inexpensive crop like onions”, says Karthik Jayaraman, co-founder of Waycool, an Agri supply chain company that sells about 800-900 tonnes of onions every month. But that may well change as the climate warms.

Better (cold) Storage<

A large part of India’s winter crop rots away. A warmer climate will only make the rotting worse. As Ashok Gulati and Harsh Wardhan write, ‘Storages at farm level suffer losses of about 20-25 percent, which can be brought down to 5-10 percent with modern cold storages. But cold stores will cost about Rs 1.5/kg/month. These stored onions can then be released during August through first half of October, before the kharif harvest starts arriving.’

Between April to August, cold storage would add Rs 7.5 to 10.5 per kg of onions. Urban housewives would gladly pay this premium rather than the far higher price they pay today. However, this suggestion assumes modern cold storages are accessible by farmers in adequate quantities. This is not true. Maharashtra’s winter crop alone was 4.5 times the total available cold storage (working or not) in 2017. India desperately needs accessible cold storage. Karthik says onions may work well in aerated cold storage — where onions would be stored at colder temperature, but would not retain moisture. But that requires modifying our available storage. In terms of investment, there can be few better places for money to go.

If we do all this well, we will curtail spikes. But what about too low prices?

Influencing crop choice

At the heart of this problem is the misalignment of risk and reward. In well-functioning financial markets, he who takes the greater risk, gets the greater reward. In onions, that is broken. The farmer takes the risk — of climate, of water, of market — yet shares very little of the reward. I wish that an MSP (Minimum support price) coupled with government procurement would work for onions. It might if we were talking Punjab, but we are not. Traders dominate the profit pool in onions — they extend credit to farmers, cornering the produce when arrivals come and prices fall, and benefit from price spikes. As such, an MSP would benefit them, not the farmer.

How else to align risk and reward? One way is via the Farmer Producer Organisations or Agritech startups that reduce layers in the supply chain and link small farmers with storage and credit and help India manage her surplus by engaging meaningfully and continually with global markets. There is emerging start-up interest here. Waycool or Ergos are two examples. Waycool helps farmers improve yield by following best practises and improves farmer cash flow by paying farmers cash when they invoice Waycool. Given that marginal cost of capital of the small farmer hovers upwards of 50 percent, that is a big deal. They also improve farmer income by trimming layers in the supply chain. Ergos works with cereals, where by adopting better storage practices, it brings down storage losses from 25 percent to less than 5 percent. They also help farmers access far cheaper formal credit by collateralising their stored crop for formal credit, bringing transparency that lenders sorely need. They also linking farmers to buyers.

Another is the Amul Model. The Farmer Producer Organisation of today may play many of the roles Amul played in helping out small dairy farmers with market access and steady demand. When yields rose, Amul helped absorb the excess through value added products like butter and dried milk powder, which has an added advantage of being easier to store.

Market access is necessary to align risk and reward. An MSP/government procurement scheme will not achieve that. FPOs and start-ups might, and thus hold one key to stabilising the volatility in onion prices.

The writer is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, cleantech angel investor and author of The Climate Solution — India's Climate Crisis and What We Can Do About It published by Hachette. Follow her work on her website; on Twitter; or write to her at cc@climaction.net.

"Delhi air pollution crisis: Money, political will, clear data or steadfast public attention — what really matters?"

Published : Nov 10,2019

India does not have hourly, source-apportioned data across cities and neighbourhoods in an accessible format, which obfuscates public understanding and dilutes political will. The kind of staccato concern we show on air pollution cannot compete with the sustained focus of lobbying efforts

But, the problem does not appear to be getting much better. There are two factors behind this that have little to do with politics or policy.>

Identifying Herbie – the data

To solve manufacturing issues, one often conducts a de-bottlenecking exercise. The Goal by E Goldratt speaks of a protagonist guiding a group of schoolboys on a hike. The boys are too slow. By observing the gap between the boys, the protagonist realises that the group can only move as fast as the slowest walker, Herbie. But, if he can make Herbie walk just a little faster (by distributing the weight of Herbie’s backpack with the other boys), the whole group speeds up. Essentially ‘Herbie’ represents the one process (or thing or person), whose performance improvement can have dramatic impact on the overall process.

What is the Herbie in solving the winter air pollution crisis?

To identify our Herbie, we need data. China had excellent, hourly, source-apportioned data for its cities and neighbourhoods. This, along with a different political reality, helped the country to significantly address its air pollution issue. India has overall PM 2.5 levels available by location, which gives us no idea of which source is driving the pollution. CEEW’s brief on emission inventories lays out the uncertainties in current efforts to understand the sources of the pollution. Such uncertainty can be hijacked by vested interests to ensure effective policy is delayed or diluted.

I cannot overstate the importance of accessible, clear robust data in enlisting public support, and thereby political support. China’s battle against air pollution received a great shot in the arm by the documentary Under the Dome, which made the pollution data accessible, and was viewed, by some accounts, a 100 million times within two days of its release. India does not have hourly, source-apportioned data across cities and neighbourhoods in an accessible format. Which means we all don’t publicly agree on who our Herbie is. This obfuscates public understanding and dilutes political will.

Dispersed pain, short attention spansEinstein put it well when he defined insanity as doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. We have a wonderfully choreographed cotillion in place:

October, silence in the media, paddy harvests begin. Fields begin to burn. October end: Diwali. October/November: Meteorological changes; winds die down, temperature falls, vertical mixing decreases. November/December: wheat planting continues; media attention peaks and shrills, ‘noted public figures’ begin to tweet, political bickering notches up, gas masks are donned, air purifier sales increase, knee-jerk policy (primarily of the seen-to-address variety) ensues, health deteriorates, flights delayed/cancelled, prayers for rain and wind increase. January: tapering begins.

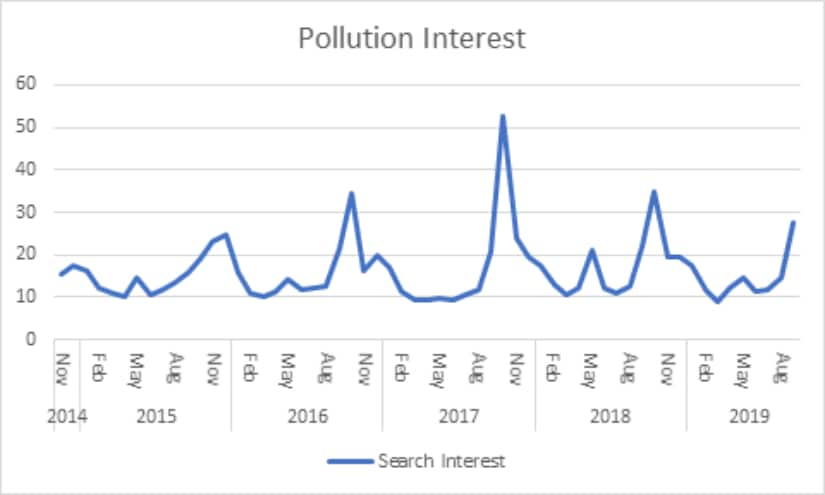

Put another way, the charade looks like this:

This is the Google trends report on air pollution in India with ramifications for political decision making. Tough decisions are hard because they have to overcome vested interests by continually exercising political will. The kind of staccato concern we show on air pollution cannot compete with the sustained focus of lobbying efforts.

There is enough funding available in the private sector, whose lives are affected by the pollution, to fund the infrastructure necessary to get the needed data. Sequencing is important here. Unless and until we fix data/public interest, it is highly unlikely that meaningful solutions will be found. What we will get is half-baked do-nothing policy. Or, in the words of my erstwhile colleague, ‘rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic’. Policy action (the realm of government) follows, not leads.

Even with the data we have, what is the Herbie?

It’s the money

Two causes stand out in the emission inventories: vehicular emissions, and the one responsible for the winter pollution spike — biomass burning. Let us deal with the latter today, and leave vehicular emissions for another time.

The financial embrace between the government and the farmer is complex. The farmer’s income is determined by procurement, the Minimum Support Price (MSP) scheme, fertiliser, electricity and interest subsidy, and, of course, skill. Access to these schemes is typically lop-sided with well-connected farmers walking away with a lion share of benefits. While that becomes important later, for now, let us understand that the farmer, much like the baker and the butcher of Adam Smith, is acting in his self-interest when he chooses to grow paddy and wheat.

Why?

Food subsidy

In 2018-19, the food procurement subsidy allocated to the Food Corporation of India (FCI) was Rs 140098 crores. Wheat and Rice account for 99 percent of the grain procured by FCI. Punjab and Haryana rank among the biggest beneficiaries of this subsidy – given that they supply 58 percent of the rice and 68 percent of the wheat procured by FCI. As a rough ballpark figure, 60 percent of the subsidy works out to Rs 84000 crores.

Great procurement – no market risk

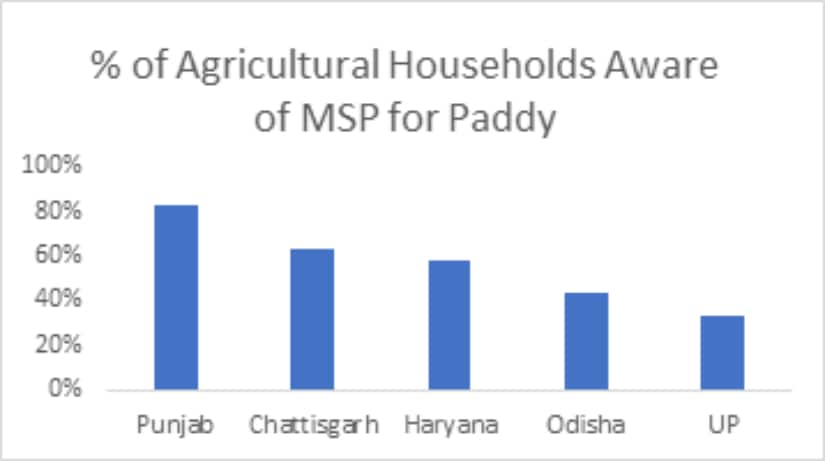

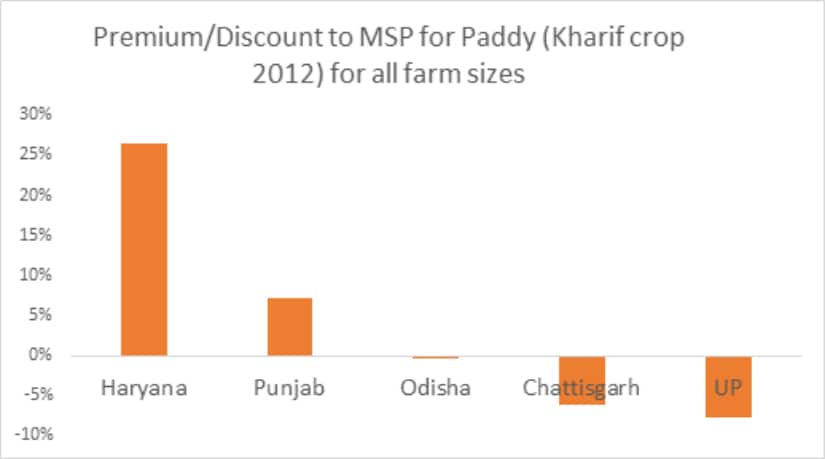

Ironically, paddy burning in Punjab and Haryana results from the local government in those states doing their job – extension, procurement and payment – very very well. Farmers are both aware of Minimum Support Price (MSP) and are able to sell their crop at that price – a rare thing in India (See Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Percentage of agricultural households aware of MSP for paddy, Kharif 2012; Source: Some aspects of farming in India, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation

Premium/Discount to MSP for Paddy, 2012; Source: Some aspects of farming in India, Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation; Note: The premium for the smallest farmers, ie those with < 0.5 Ha land seems abnormally high in Haryana, which distorts the overall premium for Haryana.

Haryana’s procurement is so damn good, that farmers from other states sneak in to sell their paddy at the Haryana mandis. For farmers in this state, there is little market risk or marketing effort required to offload their paddy and wheat – an important point to keep in mind as we lament about crop diversification.

Fertiliser subsidy

Punjab and Haryana’s share of the Rs 70,000+ fertiliser subsidy works out to over Rs 8000 crores. Moreover, the incentive to convert stubble to compost is dampened when free fertiliser is available.

Power subsidy and UDAY – all carrot, no stick

The 2018-19 power subsidy for farmers in Punjab is budgeted to cross Rs 6000 crores. Haryana’s equivalent was Rs 5933 crores in 2016-17. Not all of the subsidy flows to farmers growing wheat and paddy of course, but most does. There is an added nuance here: the Punjab government signed up for the UDAY scheme in 2016, whereby the Punjab state government would take over part of the debt of the state electricity board (resulting in cheaper financing), in return for operational efficiency. However, what happened is different. Punjab’s UDAY dashboard tells a disturbing story –cheaper bonds have been issued and both the Punjab state government and the Punjab state electricity board have financial breathing space. But, the other side of the MOU has not seen movement. The MOU states:

“Punjab DISCOM will endeavour to reduce AT&C losses from 16.66% in FY14-15 to 14% by FY18-19”.

In reality, AT&C losses have ballooned to over 30 percent! UDAY has lessened the pain of free electricity to the State, without the necessary operational tightening. All carrot, no stick.

Expertise and extension

Lastly, Punjab farmers in particular, are experts at growing paddy and wheat, thanks in part to great extension support from Punjab University, which results in substantially higher yields.

A one lakh crore subsidy

Putting all this together, in 2019, farmers from Punjab made a premium of Rs 10 per kilogram of paddy, substantially more than the premium of the average Indian farmer — Rs 5.8 per kilogram. The cost base here is A2+FL cost, which is fertiliser, pesticides, hired labour, seeds etc plus an imputed cost for family labour engaged.

A one lakh crore subsidy coupled with efficient procurement and skill ensures that the farmers of Punjab and Haryana will grow paddy and wheat while their water lasts.

Money talks. The eloquence of this financial calculation manifests in the falling water table of the Punjab, and the smoky skies over North India. The Supreme Court has recently weighed in, saying the state and the local bodies should be held accountable for stubble fires, on the Polluter Pays principle.

Subsidy/fine/subsidy/pollution. What a mess.

What problem are we trying to solve?

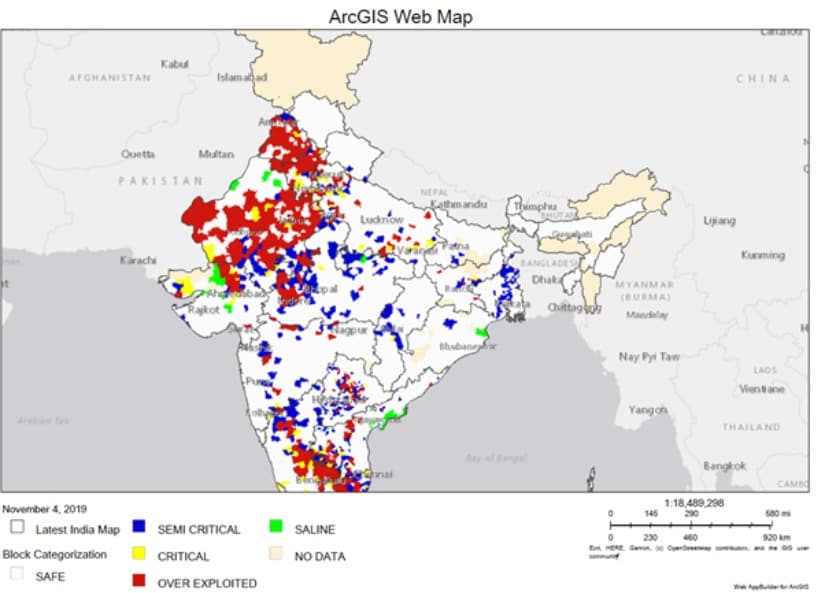

There is a larger point to made here, we will optimise what we focus on. If we want to optimise water use and soil health and lower pollution, we must change crop patterns. This is a map produced using WRI’s India water tool. The angry red of Punjab and Haryana, with little local rainfall, is almost entirely due their crop choice and irrigation practices incentivised by the MSP, procurement efficiency and practically free electricity.

If our problem statement was ‘How to reduce the impact of pollution from stubble burning’, the obvious starting point, or the Herbie, appears to be changing crop choice.

We could do that by removing subsidies, right?

While there have been rumours that the Rs 70,000 crore fertiliser subsidy might be tapered down, a recent government press release opened unequivocally:

<“There is no proposal to cut Fertilizers Subsidies.”>

Influencing crop choice by pricing electricity is also a non-starter. Punjab’s Chief Minister has been recently quoted as saying:

“his government was committed to the supply of quality power, in addition to 100% cost subsidy for agriculture and free power to various categories of consumers.”

the contribution of his state to the North Indian pollution crisis, he tweeted:

“Compensation by Central Govt to the farmers for stubble management is the only solution in the circumstances. I had written to PM @NarendraModi ji on 25th Sep & had written to him yesterday as well. The central govt has to step in and find a consensus to resolve the crisis.”

The central government could step in and say no more MSP. Or, for less of a shock, say MSP applies to only those farms that don’t burn (tackles pollution but not water). This expends political capital in a limited fashion, and may be far more effective than the solutions peddled today.

All these options are cheap in terms of ‘money’, but profligate in terms of political capital required. They don’t happen because the bottleneck resource is not money, it is political capital.

When we optimise political capital, the problem we are trying to solve is: ‘What is the politically cheapest solution seen to address air pollution caused by stubble burning.’

Very different problem statement. Accordingly, today’s solutions play about in the margins.

One of these is the Happy Seeder. The problem in paddy fields begins when the combine harvester harvests the rice but leaves a few inches of stalk standing. Farmers would burn the remaining stalks (stubble) to clear the fields for their wheat crop. The Happy Seeder cuts and lifts the standing stalks, spreads them over the entire field and plants the wheat seeds. It addresses the labour and the urgency issues in gathering the stubble. But it is an added cost in the eye of the farmer. The government gave a subsidy – an allocation of Rs 1151.8 crores (fully funded by the Centre) – towards machinery capital subsidy, awareness and setting up Farm Machinery Banks. Expensive, credible, and seen to address stubble burning. But, the subsidy given was a capital subsidy – which predictably increased the price of the machine (by some accounts almost doubled it). Smaller farmers did not find it accessible – Rs 70,000 (even with the subsidy) is a lot of money for a smaller farmer. Farmers also complain that using the machine is too expensive (the combine harvester needs an additional straw management system for the Happy Seeder to work well, which sucks up more diesel) and that they should be paid another subsidy to not burn.

Other solutions include alternate uses for straw including biogas, pellets for thermal plants or even cutlery. But the prerequisite for all of these is an efficient and cheap logistics network that can collect straw from thousands of farms in the span of two weeks. Not impossible, but not easy. At least, not until fertiliser subsidies lower the attractiveness of substitutes. Sameer Nagpal, who runs Sampurn Agriventure, the only biogas plant in India that works off paddy straw, cites several issues in caling up. One is that the economics of his biogas plant work only if he sells the compost it generates as a by-product. Organic compost is among the most expensive (and effective) fertilisers available. But farmers, traditionally fearing a new face, are wary of buying expensive black ‘stuff’ from a new entrant, and can, moreover, make the compost themselves.

The other is that the current power purchase rates offered by state electricity boards do not cover the costs. In late-2018, the Indian government introduced the SATAT, or the Sustainable Alternative Towards Affordable Transportation, initiative that looks at a decentralised model for biogas with committed offtake by a large petroleum company like IOC. The has made the economics of biogas more compelling, which is a positive sign. The bottleneck remains logistics, or the financial incentive for creating the logistics infrastructure. Something that today’s subsidy regime is clouding.

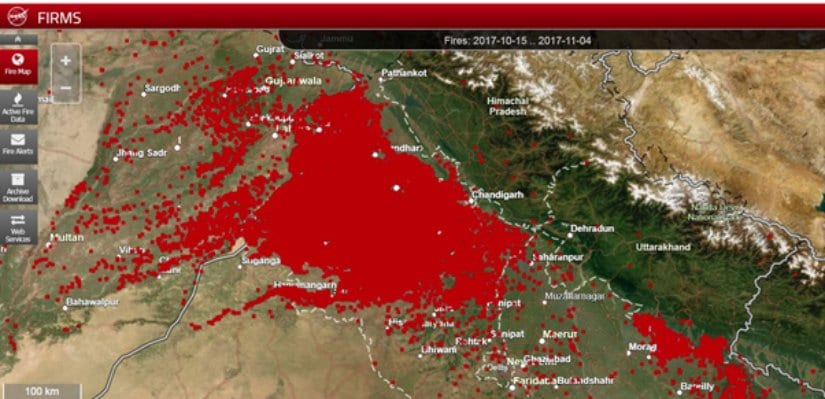

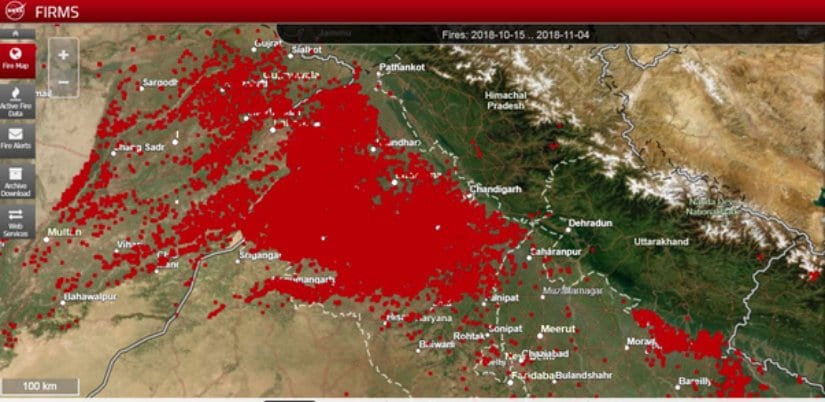

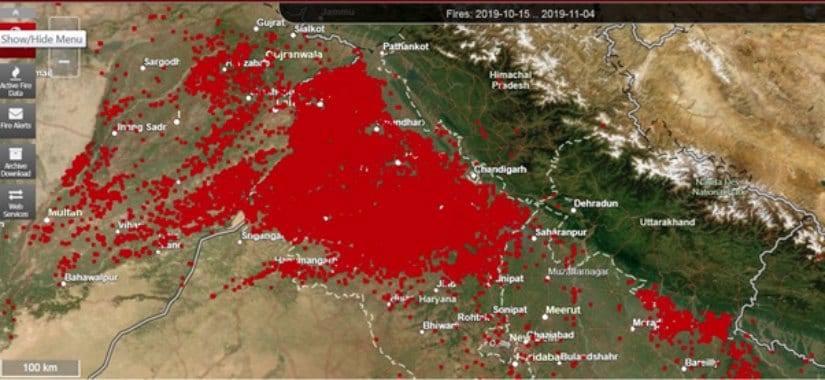

The impact of the peripheral measures in the time series of images from NASA FIRMS from 2017 to 2019 from 15 October to 4 November in each year*:

NASA Firms Image of 2017 fires between Oct 15 - Nov 4

NASA Firms Image of 2018 fires between Oct 15 - Nov 4

NASA Firms Image of 2019 fires between Oct 15 - Nov 4

Negligible reduction.

Let’s be clear: Only granular, frequent, source-apportioned, publicly-accessible data will reveal the true ‘Herbie’ to all constituents. This will (hopefully) engender the unwavering public attention, which will strengthen political will to take action on the true ‘Herbie’.

Everything else is waffling.

*We acknowledge the use of data and imagery from LANCE FIRMS operated by NASA's Earth Science Data and Information System (ESDIS) with funding provided by NASA Headquarters

The writer is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, cleantech angel investor and author of The Climate Solution — India's Climate Crisis and What We Can Do About It published by Hachette. Follow her work on her website; on Twitter; or write to her at cc@climaction.net.

Climate change created breeding ground for ISIS in Syria. India is making similar mistakes

Published : Jul 07, 2019

Climate change created breeding ground for ISIS in Syria. India is making similar mistakes

The ongoing tragic Syrian crisis provides a frightening case-in-point of what can happen as more countries face water shortages. This is particularly relevant for India, because India is committing many of the same mistakes that the Syrian government made.

Peter Gleick has written an excellent paper underscoring the connection between climate change and the Syrian crisis. Syria is a very dry country, receiving about 250 mm of rain per year. To provide some perspective, India receives more than four times that number. With so little rain, Syria relies heavily on water from other sources like the Euphrates river and groundwater.

The problem began as Syria’s population skyrocketed – from 4.5 million in 1960 to over 21 million in the next 50 years. This meant that even after extravagantly using their groundwater, there was less water to go around for each person.

The problem worsened when Turkey built the Ataturk dam across the Euphrates river in the early 1990s. Damming the Euphrates reduced the amount of water flowing into Syria by a third. Rising populations combined with falling water availability meant the amount of water available for each person shrank to less than 900 cubic metre of water per person per annum – well below what hydrologists define as scarcity.

This meant one thing: Syria had essentially no wiggle room when the climate began to change. And the climate did change. The frequency and severity of droughts in the Mediterranean region have increased in the past 30 years, in line with the effects of climate change. From 1900 to 2005, Syria experienced six major droughts. Five of these lasted just a season, while the sixth lasted for two seasons. The latest drought, however, changed all that. The severe five-year drought that began in 2006 has been called ‘the worst long- term drought and most severe set of crop failures since agricultural civilizations began in the Fertile Crescent many millennia ago’.

The drought by itself need not have translated into crop failures and food shortages. As we shall see later, Syria’s neighbour Israel also fell prey to the same drought. But while Israeli farmers thrived, Syrian farmers were decimated.

What happened? Government policy played a major role in architecting Syria’s problem, by encouraging poor crop choice – cotton and wheat, and propagating wasteful irrigation methods. Syrian farmers relied on extravagant flood irrigation and about half of their irrigation systems depended on groundwater. As the amount of rainfall decreased, farmers used their groundwater more and levels began to fall. As water levels fell, it became more expensive to draw out the water that remained until, finally, water wells began to run dry. In 2005, the Syrian government put a ban on drilling wells, but widespread corruption meant that the ban was not uniformly enforced.

There is a chilling quote in the Gleick paper that speaks of the authority’s relationship with the farmers who ‘are suffering and complain that they have had no help from the authorities who tell them what type of crops they have to plant, and have a monopoly on buying up what they produce.’ When poor water policy met with extreme climate change, the result was tragedy.

The UN sent staff to see how to help. The chosen representative, Abdullah bin Yehia’s note on what he found makes for disturbing reading: ‘The UN Interagency mission estimates that some 2,04,000 families (around one million people) in north-eastern Syria are food insecure…the needed assistance is far beyond the Government capacity and resources…many herders have incurred huge losses that they might not recover from for several seasons to come… Migration of rural population towards less water stressed urban areas was in 2007/2008 higher by 20–30 per cent than in the previous years due to impact of the drought, loss of livelihoods and water shortages.’

This cable by Yehia, calling the situation a ‘perfect storm’ was written in 2008. The report spoke of families who had lost everything, crop yields dropping to less than half of the long-term average, families selling livestock at a third of their fair price, diarrhoea, malnutrition, the works.

A report from WikiLeaks (Cable 08DAMASCUS847_a) says that the UN representative asked for about $20 million to assist roughly one million people for six months. That’s $3.4 per person, or about `200 per person per month. A bargain, one would think – but one met with relative indifference from the global community.

This indifference was the spark that ignited the tragedy into violence. Another release from WikiLeaks, of a despatch from the US Embassy in Damascus acknowledges the UN appeal and mentions that ‘this social destruction would lead to political instability, Yehia told us.’ The cable, however, then goes on to say that ‘given the generous funding the US currently provides to the Iraqi refugee community in Syria…we question whether limited USG resources should be directed toward this appeal.’

Millions fled to crowded urban centres such as Aleppo because there was no other place to go. ‘Farmers could survive one year, maybe two years, but after three years their resources were exhausted. They had no ability to do anything other than leave their lands,’ says Richard Seager, professor at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory. The people who lost their crops and farm animals left for the cities with next to nothing. All told, about 1.5 million people moved to cities and urban camps. Disillusionment because of lost livelihoods combined with large groups of unemployed young men congregated in crowded urban camps make for an incendiary mixture, that provided kindling for the Syrian uprising and later acted as ripe breeding grounds for ISIS.

Reading about this in 2018, it seems almost ludicrous for the seeker of relief to have been denied the $20 million request. The US government has spent more than a hundred times that amount fighting the ISIS in less than a year leading up to May 2015. By 2016, more than 4.8 million Syrians had fled their country, while the migration crisis was on everyone’s lips and votes. It became the bogeyman used by politicians to rile up their conservative support base. This is one ‘what might have been’ that policymakers around the world should be paying close attention to – the importance of one’s own actions while the climate warms.

In the next years, many parts of the world will become less liveable and, in extreme cases, inhospitable to human life. What does the world expect those living there to do? Keel over and die? That’s an unfair ask and is unlikely to get the desired response. Consider the following scenarios and questions.

First, large masses of people, travelling not in flimsy rubber dinghies in the dead of night but in armed ships in the light of day, would move to cooler countries. Some hot and dry countries possess nuclear arms. They cannot be stopped easily. Before you dismiss this as hogwash, consider for a moment that the north-west part of the Indian subcontinent could see water availability plummet and temperatures rise by 5°C in this century. Pakistan is India’s neighbour – sharing India’s fate geographically and climatologically. What do you think will happen here?

Bangladesh is slated to be one of the global hotspots affected by climate change. Rising seas, flooding, storms (coupled with unwise groundwater choices) will all contribute to yet another storm in India’s backyard.

South Asia is projected to see an internal migration of 35.7 million people on average by 2050, if we continue with business as usual. These migrants are projected to leave Bangladesh, the northern Indo- Gangetic plains, the corridor between Delhi and Lahore, and coastal regions such as Mumbai, Chennai and Dhaka. Where will they head to? In India, for instance, Bengaluru and interior Chennai are two ‘in-migration’ hotspots, but are these places capable of housing millions more?

"Chennai water crisis: Way ahead could encompass decentralised sewage treatment, solutions matching pain with gain"

Published : Jul 05, 2019

If by some miracle, the population shrank, our water bodies were restored, our economic model changed, and citizens voted for water management — the Chennai water crisis would vanish.

In casting our eye over ever-faraway sources of supply, we lose sight of what is in our midst: our proximate water bodies — the ones that remain.

However, while rejuvenating water bodies is great for translating seasonal rainfall into perennial water supply, we are ignoring a hyperlocal perennial source: sewage.

This is the final column in a four-part series on the Chennai water crisis. Read more from the series here.

***

If we could wave a wand that caused the population to shrink, restore our water bodies, change our economic model, and get our voters to vote for water management — the water crisis would vanish.

To wit, Chennai was early in the game in notifying groundwater legislation in 1987, via the Chennai Metropolitan Area Groundwater (Regulation) Act. To judge the toothlessness of the act, consider an extract from the Act:

“No person shall sink a well in the scheduled area unless he has obtained a permit in this behalf from the competent authority.

(2) Any person desiring to sink a well in the scheduled area shall apply to the competent authority for the grant of a permit for this purpose and shall not proceed with any activity connected with such sinking unless a permit has been granted by the competent authority.”

In 2002, the Act went on to say that one needed to get a license for drawing groundwater for non-potable purposes.

If it were not so tragic, the level of transgression is almost funny. The government perhaps realising this, repealed the Act in 2013, with one official being quoted as saying, requiring persons having over one HP pump set to register with the proposed Groundwater Authority, would have led to “public outcry.”

So what can we really do?

Chennai water crisis Way ahead could encompass decentralised sewage treatment solutions matching pain with gain

A man uses a hand-pump to fill up a container with drinking water as others wait in a queue on a street in Chennai. REUTERS

Local effort in rejuvenating water bodies

In casting our eye over ever-faraway sources of supply, we lose sight of what is in our midst: our proximate water bodies — the ones that remain.

My husband grew up near the Chitrakulam tank in Mylapore — a neighbourhood in Chennai. He remembers that in the mid-80s, the groundwater had dried up, and the hand pump in the neighbourhood did not work, leaving the residents at the tender mercies of tanker water. The tanker would arrive at any time, and the residents would have to rush at any hour to collect water for their daily needs. Sometimes the tanker would come only every other day. At that time, the tank was dry and filled with rubbish — so overgrown with weeds that the children could not even play cricket on it. There had been no theppam (tank festival) for many years. Then one local “maama”, as my husband puts it, took the initiative to get the tank cleaned. Others pitched in and soon, the atmosphere improved. The tank filled when the rains came. The local community began to speak of the historic significance of the temple and the temple tank, to cement the respect for the tank. Once the virtuous cycle set in, groundwater levels improved.

(Update: The tank is dry again, underscoring the importance of continuous community engagement.)

At a larger scale, the Chennai Smart City Limited, a special purpose vehicle established to execute smart city projects, is taking up tank rejuvenation on a war footing. Partnering with the Greater Chennai Corporation, civil society, resident association and CSR arms of corporates, they have taken up over 200 water bodies for rejuvenation. Of these, 12 have been completely rejuvenated, helping replenish groundwater levels in the respective localities, while work is in progress in another 73.

Chennai water crisis Way ahead could encompass decentralised sewage treatment solutions matching pain with gain

Before and After shots of a rejuvenated Omakulam. Image courtesy Chennai Smart City Limited.

I have a little more insight into the restoration of the Sembakkam lake, which is being coordinated by the Nature Conservancy. The importance of getting residents to buy into the effort, and most importantly of clearing the inlet and outlet channels in system tanks cannot be overemphasised. The difficulty of handling encroachment becomes easier if a motivated group adds their might to the task.

Rejuvenating water bodies is great for translating seasonal rainfall into perennial water supply. But we are ignoring a hyperlocal perennial source.

The glory of sewage

Funnily enough, what really excites me, is sewage.

Let me explain.

On the supply side, it’s important to realise that not all water uses need the same quality of water. Flushing and landscaping — together accounting for a third to half our demand — can be served quite easily with recycled sewage water.

One caveat: Please do not spend time and money, fruitlessly pumping sewage to a centralised sewage treatment facility from where the treated water is not of any use to persons who generated it. Rather, the model that cities like Chennai should consider is decentralised sewage treatment. Why?

Think of the trouble of pumping sewage to a centralised location – pipes could be broken; there could be an encroachment en route which ensures your sewage never reaches the treatment station; the centralised pumping station could have a maintenance problem. Then think, what happens to the treated sewage — who does it benefit?

Instead, think of a more local solution. In your apartment, under the car park could run a sewage treatment plant. One start-up does just this — build an underground STP with no operating expenditure. I have seen (and smelled) the treated water. Its quality visually beats my muddy bathing water in Chennai, and has been tested by IIT Madras to ensure it is safe for toilet/landscape use. Think. Your bore has begun to run dry. Tanker water is expensive and uncertain. What if significantly cheaper, readily available, reclaimed water (or ‘new water’, as Singapore calls it) could serve some part of your needs?

Apartments and offices across the country are discovering for them how wonderful a resource their own sewage is. If every bulk user (schools/apartments/hotels/offices) reused their treated sewage, they could cut their water purchases by more than a third. Payback times vary based on current water price paid and recycling technology used — but falls between months to a couple of years.

Almost as important as the treatment technology is the financial envelope surrounding the sewage treatment infrastructure. Apartment complexes may balk at the capital investment, which is why some start-ups are beginning to contemplate a “water-as-a-service” model for these, underwriting the capex, and then charging apartments on a per-litre of treated water, which is far more attractive in cash-flow terms for an apartment committee. We sometimes get caught up in the glory of technology while underemphasising the context of its use. This is the importance of local innovation — understanding the context of the customer — the importance of cash flow and lack of space in framing a solution.

Secondly on the supply side, rainwater harvesting helps. One professor from Velachery says, thanks to a combination of sewage treatment and rainwater harvesting, he has no water problems. But even in a state like Tamil Nadu, a pioneer in rainwater harvesting, many structures exist on paper only. In Madurai, in data from a thousand households, less than half had active rainwater harvesting structures. This data is corroborated in Chennai by studies from the Rain Centre.

Chennai water crisis Way ahead could encompass decentralised sewage treatment solutions matching pain with gain

Percentage of respondents, for the question — Do you have a functioning rainwater harvesting system? | Sundaram Climate Institute, 2018

While greening our urban spaces allows rainwater to replenish groundwater, in our own dwellings, we can check if the rainwater harvesting structures are working to help replenish our own bores.

Demand management

Now, for demand. As mentioned, for most of us, our understanding of how much water we use is poor. The poor, who wait in line, giving up sleep and leisure to fill pots of water, have a fine understanding of how much water they use and for what. But those of us used to water flowing when we open our taps, are habituated to not care how we use our water. This is now changing. A granular understanding is key in managing demand; my house in Madurai, for instance, has 15 water meters — in a single house. That’s what helps us understand where we can optimise usage, and truly helps in locating and arresting leaks.

Here again, the Chennai Smart City is helping install meters at bulk heads. Raj Cherubal, CEO of this SPV, says, “What you can’t measure, you can’t manage. We need metering of bulk heads, commercial building and water lorries — which are some of the smart city related projects.”

On a smaller scale, another start-up helps bulk users measure and reduce their usage through sensors and analytics. By charging on a per litre basis, the company has aligned its interests with saving water and made the proposition financially palatable for apartments.

A changing scenario

At some level, the current almost-predictable crisis comes about because we think water is plentiful. It is not. Earlier in this series, we asked why Israel behaved differently from India — leaning on management and innovation, while India depended on provision.

For one, in Israel, all water is the property of the government. Israel is a dry land, much of it desert. A company or a person or a farmer does not have the right to the groundwater under his or her land. Which means that for every person, water is a limited resource with a price. This encourages management, which, in turn, begets innovation.

In India, while the government might have acted, each of us assumed the ground below us held enough water for always. We now know that is not true. Perhaps, we too now will begin to manage and innovate.

One way in which the government can help is to frame policy that encourages bulk users to manage their water. Zero discharge is not feasible — even if bulk users treated and reused some part of their sewage, they will need some ‘fresh’ water for drinking and cooking needs (not everyone can go the T-Zed way), and there will be excess treated sewage, over and above, what is reused by the bulk user. One great way to use this treated sewage is to emulate what Bengaluru has done with the Jakkur lake.

This ties in neatly with what is needed: rejuvenate a local tank, get bulk users to treat their sewage, and feed in the treated sewage after tertiary treatment into the local tank. The government will need to facilitate this by helping lay pipelines for the transport of treated sewage to a local tank and by ensuring tertiary treatment at the tank. By keeping it local, we tie in incentives — after all, neighbours will not tolerate insufficiently treated sewage flowing into their tank. And the waters in the tank will help replenish local groundwater levels that will benefit all. This moves responsibility and onus from the government to ourselves; it makes the government’s role facilitative — the key mental shift we may need to make to get ourselves out of the crisis.

The writer is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, cleantech angel investor and author of The Climate Solution — India's Climate Crisis and What We Can Do About It published by Hachette. Follow her work on her website; on Twitter; or write to her at cc@climaction.net.

Chennai water crisis: How 'great' teamwork, muddy data enabled poor management and engineered a disaster

Published : Jul 04, 2019

Chennai is overdrawing its ground water 1.85 times. The false sense of plenty is one possible reason why we have managed our water so poorly. But the second possible explanation for poor management is the lack of a good incentive mechanism — either for our politicians or our bureaucracy.

Chennai water crisis: How 'great' teamwork, muddy data enabled poor management and engineered a disaster

Chennai is overdrawing its ground water 1.85 times

This false sense of plenty — because we cannot perceive just how much water there is underground — is one possible reason why we have managed our water so poorly

But the second possible explanation for poor management is the lack of a good incentive mechanism — either for our politicians or our bureaucracy

This is the third in a four-part series on the Chennai water crisis. Read more from the series here.

***

Why does anyone manage any resource poorly?

One answer is that they think it is not a scarce resource. The other is that one believes they can get away with it — i.e., there will be no consequence — either positive for good performance or negative for bad performance.

Take water for instance. There is a hue and cry today because the uncertainty of availability pinches the bottom line or takes away more sleep than you had bargained for. But thus far, as long as ground water aquifers kept feeding the borewells, most of us were okay with the bargain, Recall: Chennai is overdrawing its ground water 1.85 times! This false sense of plenty — because we cannot perceive just how much water there is underground — is one possible reason why we have managed our water so poorly. If that is indeed the case, going forward, as groundwater runs scarce, we might manage water better.

But the second possible explanation for poor management is the lack of a good incentive mechanism, either for our politicians or our bureaucracy. Let us see why by taking one very visible sign of mismanagement: encroachment.

Enabling Encroachment — Teamwork Helps

If we had wanted to engineer a crisis, we could not have done a better job. Deficiencies in public infrastructure make India’s cities smaller than they should be, meaning urban water bodies are very attractive as land parcels. As a city grows, new neighbourhoods on the peripheries often lean into water bodies and do not have municipal water connections. That takes time. What the residents in these new neighbourhoods usually do is to sink a borewell, and begin to draw water from below the ground. You turn on the motor, and your sump fills. You cannot see the water, and after years of reliable use, you think it permanent, and therefore do not need to pressure the corporation for a commission. Your builder might have leaned on a water body and built where he was strictly not supposed to. It might even be awkward to ask for a water connection. After all, there is so much water available underground. Until one day, it runs out, and your life turns upside down. Chennai water crisis How great teamwork muddy data enabled poor management and engineered a disaster

A woman uses a hand pump to fill up a container with drinking water in Chennai. REUTERS

A 2017 CAG report says that of some 1,554 water bodies in Chennai, less than a third were surveyed. In those, 36,814 encroachments were identified, of which 10,764 encroachments were evicted — resulting in a pitiful 170 water bodies being restored to their original capacity. Importantly, no encroachments were cleared in 2014-15, or 15-16, the last two years covered in the report. Some of the encroachment, states the CAG report, are by local bodies themselves, often for disposal of solid waste or for accommodating slum dwellers evicted from some other part of the city.

The report goes on to say:

“To an audit enquiry, the executive officer, Peerkankaranai Town Panchayat, replied that as occupants of all illegal colonies inside water bodies in the Town Panchayat were issued with Patta by Revenue Authorities, taxes were collected and basic amenities like roads, streetlights and water supply were provided.”

Encroachers, rather than being evicted, were being encouraged!

Clearing encroachments has no obvious upside for the person(s) doing the clearing. The evictees will protest, go to court, stall the proceedings, take away time you don’t have on court attendance, lobby powerful interests, make your life hell. It’s unlikely that you will get either more money, or more power by evicting them. Leave them be… After all, everyone is doing it.

And when everyone does it, it doesn’t seem quite so wrong.

Take the example of Pallikaranai. Wetlands are literally the kidneys of a landscape as they filter contaminants and soak up water and replenish groundwater aquifers. Pallikaranai is the main wetland of Chennai. Back in 2003, the chief economist of one of India’s largest real estate consultancy firms declared Pallikaranai to be a prime investment destination, where “prices could double in nearly five to five-and-a-half years’ time”.

Developers and investors were quick to jump on what seemed a ‘too-good-to-miss’ opportunity, and the wetland was slowly eaten away (See Figure 3 below). The icing on this unpalatable cake is that there is an enormous landfill cited on Pallikaranai. That’s really like a toxin-loaded syringe released into the filtered blood supply coming out of your kidneys. Chennai water crisis How great teamwork muddy data enabled poor management and engineered a disaster

Figure 1: Pallikaranai Google Earth images from 1986, 1996 and 2019

This has been going on for decades. The advertisements for these developments have been proudly and flamboyantly carried in the same newspapers where opinion columns bemoan the water crisis today. Thousands bought flats and take jobs in the developments that have come up on the feed plains of these wetlands. It’s been one heck of a team effort — which means it requires a team effort to reverse.

A Problem of Data

Of course, the state of data doesn’t help.

For instance, in what is definitely a critical juncture in Chennai’s water story, it is unbelievable that we do not have a firm handle on just how much water we are using. Second, when looking at the level of metering, estimates range from 20 percent of water consumed being measured, primarily of bulk customers, to over 60 percent. Even the share of different supply sources is not too certain. When large scale protests have not broken out at a time that a city’s main reservoirs are empty, it shows quite clearly that there are other sources coming into play. Experts opine that the level of metering is far lower, and understanding where demand is coming from is a big problem.

To give you a contrast, in my factory, we have a hundred water meters to understand precisely where, when and how we use water. This allows us to reduce demand in a cost-effective fashion. Moreover, when the data is so uncertain, it reduces the motivation to act. To give a medical analogy: contrast your doctor saying, “You will die in six months if you don’t stop smoking” to one doctor saying, “I’m not sure,

maybe you will live for 20 years even if you smoke,” while another says, “You could live for five years or two months, I’m not sure”. Very different calls to action.The Hit to Supply

The problem is that encroachment reduces water supply.

For instance, Chennai gets only a miniscule fraction of the 15 TMC it is due from the Krishna waters, at least in part due to encroachment and illegal tapping.

Next, consider this set of images over two decades of the Porur Tank.

Chennai water crisis How great teamwork muddy data enabled poor management and engineered a disaster

Figure 2: Porur Lake; images from Google Earth

The image top left is from 2000, courtesy Google Earth. The one on the bottom left is taken in 2010 — you can see how the city has begun eating away at the greenery surrounding the lake. Many Indian cities have a system of cascading tanks, where the surplus from one, flows downstream. Encroachments cutting connecting channels reduces the effectiveness of the entire system. Moreover, by replacing green with concrete we hit percolation — i.e., the flow of rainwater into the ground, rather than into a stream and thence to the sea. Lastly, local land use change — especially cutting forests — has shown to impact local rainfall. Studies put the contribution of forests to terrestrial rainfall (rain over land) at 40 percent. That’s huge. Encroachments also hurt flood resilience — the rivers and the tanks help suck in some of the excess. Chennaiites are crying because there is no water now. Come November/December, they will be cringing because there is too much.

India, with a peculiarly seasonal water supply, cannot afford to continue to decimate her storage mechanisms.

Let’s Not Forget the Climate

Now, add climate change. It has become somewhat fashionable to load all woes on climate change. It’s useful too — it absolves us from even taking the mental responsibility for a problem. In this case, there are, in my mind, two ways by which climate change does exacerbate this crisis. First, when it gets hotter, and the incidence of heatwaves rises, one needs more water to cool down. Thus, demand rises. Also, the fraction of water that evaporates goes up, reducing supply. Second, the number of rain days comes down as the planet warms — this means the fraction of rainfall that “runs off” increases, especially when we reduce the amount of space that can soak up the run off. This cuts supply, and makes us flood-prone (something Mumbai residents can empathise with just now).

In financial terms, global warming upsets both our water balance sheet and income statement, increasing our vulnerability. Perhaps that’s a good thing — we may just need this kind of warning to clean up the system.

Next: What can be done.

The writer is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, cleantech angel investor and author of The Climate Solution — India's Climate Crisis and What We Can Do About It published by Hachette. Follow her work on her website; on Twitter; or write to her at cc@climaction.net.

Chennai water crisis: Why provision, while alluring, couldn't slake a growing city's thirst

Published : Jul 03, 2019

Quenching Chennai’s thirst by leaning solely on provision is like trying to fill the fabled yaksha’s seventh pot of gold. Mridula Ramesh

Chennai water crisis: Why provision, while alluring, couldn't slake a growing city's thirst

To blame the lack of rainfall alone for Chennai's water woes is wrong As the city's population exploded, newers ways of provisioning for its water demands were put into motion But there was little focus on management of existing water resources The story of trying to satiate Chennai's thirst for water has much in common with a folk take about a barber who was given seven pots of gold by a yaksha

This is the second in a four-part series on the Chennai water crisis. Read more from the series here.

***நீர்இன்று அமையாது உலகெனின் யார்யார்க்கும், வான்இன்று அமையாது ஒழுக்கு.

This couplet from the Thirukkural was written by a resident of Chennai 2,000 years ago. It means: Without water, no person — however important — can function. Thus, without the clouds and rain, order cannot be maintained.

The Northeast monsoon in important to Tamil Nadu.

“The northeast monsoon (NEM) season of October to December (OND) is the chief rainy season for this subdivision with 48 percent (438.2 mm) of its annual rainfall realised during this season,” says the Indian Meteorological Department.

But in 2018, the Northeast monsoon was a failure — bringing 24 percent less rain into Tamil Nadu than it was projected to. Chennai was amongst the worst hit, getting just 353 mm, or less than half of the 790 mm it was supposed to get.

As the months rolled by, life for Chennaiites did not get better. Between 1 March to 31 May 2019, called the pre-monsoon season, Chennai got no rain. In normal times, it should get about 58.5 mm on average. The heat did not help either — we are in the midst of a mild El Nino, bringing with it the possibility of higher temperatures and less rainfall during the Southwest monsoon.

But to blame the rainfall alone is wrong.

Providing for Chennai’s thirst vs adapting demand to existing water resources

For millennia, people of Chennai have relied on tanks, shallow wells and its three seasonal rivers — the Adyar, the Cooum and the Kosasthalaiyar — for their water. Much like other regions with scanty local rainfall fed by seasonal rivers, there was a system of cascading tanks that provided much-needed storage to stretch out the water through the year.

Let us focus on one of the rivers, the Cooum. Anyone who drives past the Cooum today knows the smell of sewage that penetrates even the most tightly closed windows.

Chennai water crisis Why provision while alluring couldnt slake a growing citys thirst

A man walks through the dried-up Puzhal reservoir, on the outskirts in Chennai. REUTERS

The Cooum river originates from Thiruvallur, and receiving surplus waters from the Kosasthalaiyar and Palar, meanders through Chennai before emptying in the Bay of Bengal, draining about 505 square km enroute. Its origins are enshrined in legend (read the fascinating stories here). The Skanda Purana speaks of how once Shiva, the God of Destruction, forgot to worship Ganesha, the God of new beginnings, before setting out to destroy three asuras (demons in Hindu lore). Ganesha was Shiva’s son, but rules are rules, and such a breach meant a break in the axle of Shiva’s chariot. To balance himself, Shiva planted his bow to the ground, and the ancient underground Palar (the surface waters of which rise in the Nandi Hills near Bengaluru) rushed up to wash his feet. These waters became the Cooum. Such was the power of the river, that even sins that could not be cleansed by the Ganga would be washed away by a dip in this river.

That was then. Today, one would be ill advised to take a dip in the Cooum, which serves as a glorified sewer for Chennai.

The slow death of the Cooum began in 1872 when a weir was constructed by William Fraser across the Kosasthalaiyar to divert its waters to Cholavaram and thence to the Red Hills lake — eventually to reach the Kilpauk water works. But the Cooum sustained itself by the waters of the Kosasthalaiyar, so this diversion stuck a body blow. The reason for the weir and the subsequent water works at Kilpauk was rooted in providing drinking water for the rapidly growing Chennai metropolis. It was the first rung on the ladder of the provision approach, rooted in a command-and-control philosophy, as opposed to the adaptation approach, such as a system of cascading tanks embodies.

The problem with the provision approach, as we shall see, is that while it did keep pace with the demand trajectory, in part because it placed no bounds on demand. Remember, in earlier times, one lived by a river, or took out water from a well. Any water used needed arduous work, which impressed its own stamp of value on water. Water laboriously begotten was thus judiciously used for bathing, washing and cleaning. There were likely not many profligate showers, no flushing toilets or wasteful washing. But as Chennaites grew wealthier and experienced water at their doorsteps, they became more relaxed about their water use. Demand really took off, however, when the population exploded.

In the 20th century, like many other cities in India, Chennai’s population skyrocketed.

Chennai water crisis Why provision while alluring couldnt slake a growing citys thirst

Chennai water crisis Why provision while alluring couldnt slake a growing citys thirst

Figure 1: Chennai Population, Census of India

A higher urban population means higher year-round demand. This is a problem considering India’s (and Chennai’s) highly seasonal rainfall. This kind of rain needs the percolation infrastructure and storage to allow it to be used through the year. Leonardo Di Caprio’s statement that only rain can save Chennai is not strictly true — rain, coupled with adequate storage mechanisms and demand management can. But what this high perennial demand does is that is increases the value of sources that supply water during the lean, cruel summer months; i.e., the desalination plants and groundwater. When the Southwest monsoons are good, sources like the Veeranam lake become somewhat reliable. (Aside: in such a situation, it is peculiar that we are underusing one local, perennial source. We will come back to this later.)

Not only did population grow, but importantly in water management terms, population density grew as well, from about 7,000 people per square km to over 26,000 people living in that square km. Each of these people needs water to drink, wash and use in their toilets, which meant the water management authority had to provide larger quantities of water at any given time.

Chennai water crisis Why provision while alluring couldnt slake a growing citys thirst

Figure 2: Chennai Population Density, Census of India

To keep pace, Chennai tried to augment supply, or increase provision. It did so by constructing the Poondi reservoir in 1944, by increasing the height of the lake bunds — Cholavaram, Red Hills and Poondi in 1972 — increasing the total storage to 6296 mcft.

The Metrowater website states,

“The system was then designed for a supply of 115 lpcd [litres per person per day] for an estimated population of 0.66 million expected in 1961.”

But water demand of the city outstripped the planner’s anticipation. In 1962, irrigation rights of the three tanks were purchased and their entire supply was earmarked for the city’s drinking water. But that was not enough.

Then, Chennai succumbed to the lure of the borewell. The Metrowater website says,

“Based on the UNDP studies carried out during 1966 to 1969, ground water aquifer was identified at Tamaraipakkam, Panjetty and Minjur in the Araniar-Kosathalaiyar Basin (AK Basin) located north of Chennai. These three Well fields were developed for abstracting water at an estimated yield of 125 MLD.”

When this too failed to quench Chennai’s thirst, the government continued to climb up the provision ladder, by signing an accord with the Andhra Pradesh Government on 18 April 1983 for drawing 15 TMC of Krishna water to Chennai City. Interestingly, even in the design, a fifth (3 TMC) of the water was expected to be lost to evaporation! Who cared — after all, provision was the focus, not management.

Meanwhile, at least on paper, with Chembarambakkam’s water, the on-paper storage capacity of Chennai’s lakes rose to 11,527 mcft in the 1990s.

But a future water plan showed a looming gap, and drinking water crises continued to erupt frequently. New sources needed to be identified. In 1996, Chennai Metrowater and the World Bank conducted an assessment of various alternatives for supplying additional bulk water to the city. The cheapest alternative appeared to be the groundwater from the AK aquifer. Farmers with rights to water in the aquifer were quite happy to sell their water share to Metrowater.

Yet still, Chennai’s thirst refused to be satiated. Chennai then turned its thirsty eyes to the Kaveri waters, through the Veeranam Lake. This was an old idea: the foundation stone for the Veeranam project was laid by erstwhile chief minister Annadurai in 1967. The Veeranam Lake lies about 236 km from Chennai at the tail end of the Kaveri system — the lake is fed by a canal off the Coleroon, which in turn gets its water from the Kaveri. To illustrate the pecking order of this water supply: Tamil Nadu has to get its water share of the Kaveri, then the Coleroon has to get its water share, then the farmers dependent on the Coleroon have to get their water share, then the farmers dependent on the Vadavar channel (which feeds the Veeranam Lake) have to get their water share, after which drinking water can be supplied to Chennai. But no one ever said that imagination and spin are constraints of provision! In times of plenty, this will work. But does one ever complain during times of plenty?

But even the waters of the Kaveri could not sate Chennai’s thirst. Chennai turned to the sea. The sea was an inexhaustible but expensive source that could be tapped through desalination. The first of Chennai’s desalination came online in 2010, with second coming online in 2013. It is reported to cost Rs 1.36 crores every day in just O&M costs to procure this desalinated water. Chennai has just laid the foundation stone for another desalination plant. Chennai water crisis Why provision while alluring couldnt slake a growing citys thirst

People sit around a tower for measuring water depth in the dried-up Puzhal reservoir, on the outskirts in Chennai. REUTERS

As 2019’s shortage intensifies, new sources of provision are explored or at least announced — including the possibility of transporting 10 million litres of water per day by rail from Jolarpet, eliciting an instant threat of reprisal from a rival political party.

Readers maybe noticing a complete absence of focus on management. Contrast Chennai’s history with Israel (with roughly comparable populations). Why did Israel focus on management and innovation when Chennai continued to rely on provision? This is an important question, and one we will return to later.

Until now, we have spoken only of official water supply. But as the city expanded outwards, its water supply steadily reached underground. There are few estimates of just how much water private borewells extract in Chennai, but it is vast, and it is unregulated. To wit, the Central Ground Water Board had declared in 2017 that Chennai had overdrawn its ground water 1.85 times! That means for every litre of ground water available, Chennai was withdrawing almost two litres. We have discovered for ourselves just how sustainable that is.

With all this provision, in the summer of 2019, Chennai is experiencing 50 shades of Day Zero.

There was once a cheerful barber, who, though poor, was content in his life. One day, when crossing a wood on his way home, he heard a yaksha’s (celestial being) voice say, ‘O barber, when you go home you will find seven pots of gold. If you don’t want them, return them to me as you found them’. The barber rushed home and found there were indeed seven pots. Six of them were filled to the brim with gold coins. But the seventh was half empty. Disappointed, he determined that he would fill the pot. He worked harder at first, putting his extra earning into the pot. But it remained half full. He scrimped on his expenses, he sold his wife’s jewellery, he even got into debt. But the seventh pot remained stubbornly half full. And the barber’s cheerful demeanour vanished.

The king, noticing this, asked him if the barber, by any chance, had a yaksha offer him seven pots of gold? The barber was amazed. He first stared at the king and then nodded sadly. The king, smiling, said, ‘I too was offered the seven pots of the gold, and it took me a war to realise the seventh pot would never be filled. Return the pots and be happy as you are.’

Quenching Chennai’s thirst by leaning solely on provision is like trying to fill the yaksha’s seventh pot of gold.

When provision is so inadequate, why do we lean on it so much? One possible explanation is that it works well in a democracy, especially one with diverse voter interests and short voter timeframes. For a politician, provision is tangible proof that he is doing something for voter interests. It also can serve as a rent-provision mechanism. Management is slower, less glamourous, more decentralised. Importantly,

impatient voters have often not rewarded sound water management. For more on this, read this, this, this and this.

But for any road out of this crisis is through the valley of management, which is where we go to next.

The writer is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, cleantech angel investor and author of The Climate Solution — India's Climate Crisis and What We Can Do About It published by Hachette. Follow her work on her website; on Twitter; or write to her at cc@climaction.net.

Chennai water crisis: Citizens' Day Zero experiences impacted by locality, income and consumption

Published : Jul 02, 2019

In the Chennai water crisis, there are 50 shades of (Day) Zero: your personal crisis depends on where you live, how rich you are and how much you consume

Chennai water crisis: Citizens' Day Zero experiences impacted by locality, income and consumption

What is puzzling is the sheer variety of crisis experiences — some are unaffected, while others have seen lives completely disrupted.

This diversity acts as an impediment to meaningful action — for every person protesting with empty pots, there is someone completely untouched.

To understand this diversity of experience, it’s useful to think of the crisis along three dimensions: geographic, economic, and quantity consumed.

This is the first in a four-part series on the Chennai water crisis. Read more from the series here.

Apprehension was my primary emotion when I landed in Chennai on the night of 18 June 2019, for the BBC declared that, Chennai — India’s sixth largest city — had pretty much run out water.

“Veetila thanni irrukka (Is there water in the house)?” I asked my driver.

“Mmm. Irrukku (Yes, there is),” was his reply.

“Unga veetila thanni varuda (Is water coming at your house)?” I asked again.

“Ippothaikku varudu (For now, yes),” he replied.

Hmmm. Was it really a crisis?

But then he added, “My daughter has been asked to take four bottles of water to school. Her water bottles weigh more than her books. Her school has run out of water.”

Okay. Maybe it was a crisis.

The next morning, I stared at the ever-so-slightly brown bathing water in the bucket. Not the most cheering of sights. As the morning unfolded, Chennai appeared to be running as always, on the surface. The traffic was high near Madhya Kailash, and the trees in Mylapore, Alwarpet, RA Puram, Adyar looked as luscious as ever. But under the surface, was a hydrological crisis brewing?

What is puzzling is the sheer variety of crisis experiences — some are unaffected, while others have seen lives completely disrupted. This diversity acts as an impediment to meaningful action — for every person protesting with empty pots, there is someone completely untouched. To understand this diversity of experience, it’s useful to think of the crisis along three dimensions: geographic, economic, and quantity consumed.

Geography

A couple of women who stayed at Teynampet said they had no running water.

“The lorry comes at all hours — there is no fixed time. We come to work. If it comes at night, we can collect it and store it, but if it comes in the day, we can’t do it. In that case, we use the hand pump at night. It takes about 10 minutes to fill a thavalai (a small pot holding about 10 litres) using a hand pump. Sometimes this water is not so good for drinking, or not enough. If we need more water, we buy.”

How much did that cost?

“It varies. About one rupee per thavalai.”

Not bad. That’s about 10 paise per litre — a lot cheaper than the 30 paise to 1 rupee per litre paid by many residents in Madurai as per the survey we were doing at Sundaram Climate Institute. The water, however, had a steeper, intangible cost — the women lost more than an hour of sleep/leisure time per day to collect the water — either in jostling for space in front of the tanker, or in waiting for the hand pump to load up their water. Lost sleep/foregone leisure translates to lost productivity.

“There is so little water that I can wash only one piece of clothing at a time,” said one woman. The women saved the water from washing dishes and bathing to use for flushing. Chennai water crisis Citizens Day Zero experiences impacted by locality income and consumption

The diversity of experiences related to the Chennai water crisis acts as an impediment to meaningful action — for every person protesting with empty pots, there is someone completely untouched. REUTERS

Some central neighbourhoods of Chennai were bone dry, with water almost the only thing on people’s minds, tongues and pockets.

“Thanni irrukka (Do you have water)?” was a great conversation-starter, where shared misery made friends of strangers.