Sundaram Climate Institute (P) Limited

In the Press

2022

Mridula Ramesh:Delhi needs brave political action but don’t hold your breath

"Water Engineering and Wealth in the Age of Ponniyin Selvan."

Published : NOV 12, 2022

Learning lost: Actions like shutting schools come with a cost to kids from less privileged backgrounds

Learning lost: Actions like shutting schools come with a cost to kids from less privileged backgrounds

Does Delhi’s plan fix those? The Delhi government proposed spraying farms with free bio-decomposer to reduce stubble burning. Farmers burn stubble to quickly and cheaply clear their fields as the gap between paddy harvest and wheat sowing is only around 10-14 days. This year, because of an extended monsoon, that gap is even smaller. Farmers complain that the decomposer needs about three weeks to work and adds to their costs. So, Punjab reportedly adopted the decomposer on less than 1% of its paddy acreage. Neighbouring Haryana fared better by significantly decreasing its stubble burning by helping farmers access stubble management machinery (like balers), using the bio-decomposer and making burning financially less attractive. It was not nearly enough. On November 3, when Delhi’s pollution was hazardous, stubble burning accounted for a third of PM2.5 pollution.

Another item on the 15-point plan is deployment of 380 teams to ensure vehicles (especially older ones) don’t pollute, and help clear congestion. But with over 7 million active vehicles on the road, this will be hard to do. Electric mobility (EM) is heralded as a future messiah, but less than 10% of vehicles sold thus far in 2022 were electric. EM needs to scale up far more to make a dent on pollution. Could Delhi try something else? Mexico City, with air so foul that birds fell dead from the sky in 1992, cleaned up its air by improving its fuel quality and increasing public transport. While Delhi’s metro is a success, the capital needs better last-mile connectivity and bus network for shorter journeys. While Delhi appears to have reduced its congestion this year (as per the TomTom index), is that by banning vehicle entry and work/study-from-home orders? These actions have costs.

To control dust, Delhi turns to smog guns (and plans to increase tree cover). While smog guns are very visible, studies place the impact of controlling dust from construction by barriers or fogging at less than 1%. As for green cover, while the forest department says it has increased, several experts put this down to flawed methodology and point instead to 77,000 trees having been felled or transplanted in the past few years. Transplanting trees is a dusty business. Having industries switch to gaseous fuels is an effective method of countering pollution, except that industries play a bigger role in summer pollution rather than in the winter spike.

Other actions, like shutting schools, are cruel in their irony. When a home has no fancy air purifier, and the child has no gadget or data to connect to class, who bears the pain of shutting schools and who reaps the benefit? Banning waste burning, while effective, hurts the poorest, who have few other options for staying warm. Are we acting against only ‘weak’ polluters? Also, banning some things while letting others go (relatively) unpunished makes people less likely to follow rules overall.

Remember London, Los Angeles, Beijing, and Mexico City have each fought against air pollution and won. Their battles began with a good understanding and agreement on what caused the pollution and was clinched with public support (or brute power in China) for strong action against polluters. In India, I sympathise with our political leaders. Stopping farmers from burning stubble is, politically, a Herculean task, since thousands of crores are spent annually to subsidise a crop pattern that encourages it. It’s hard to reduce vehicular pollution by making more space for buses in roads, when that hurts powerful people who drive cars. Taking such actions means prioritising health for all over catering to narrow interests. It is a coming-of-age moment in democracies. One predictor of this turn is sustained public attention. But since public attention on pollution has flagged even as Delhi’s air quality improved from ‘hazardous’ to ‘very unhealthy’, don’t hold your breath for brave political action. Expect more deck chairs to be shuffled.

"Water Engineering and Wealth in the Age of Ponniyin Selvan."

Published : OCT 07, 2022

As I wrote earlier, ‘Tanks are brilliant. They work in two ways – one, they collect rainwater from whichever area they directly drain, and allow the rainwater a chance to percolate into the ground, rather than ‘runoff’. Second, a subset of tanks, called system tanks, or system ‘eris’ are connected to a network of other tanks and to the river through canals. These system tanks are the beneficiaries of surplus non-local rainfall.’ Veeranarayana Eri or Veeranam Lake as it called today is such a tank.

Another example of ancient water engineering is the anai or check dam. While the Kallanai is the well known example of Chola water engineering (I’ve written of it and its fabulous engineering in my book), its more humble sister, the Sitranai has its own magnificence and tale to tell. Elegance is usually a testament to understanding, and the stark simplicity of the design of the Sitranai speaks eloquently both about the deep understanding ancient Tamil rulers possessed of river flows and a philosophy that made them work with the waters rather than trying to re-shape them.

Sitranai in full flow, (C) Mridula Ramesh

Sitranai in full flow, (C) Mridula Ramesh

The Sitranai (literally small check dam) is a gently semi-circular granite check dam built across the Vaigai near a village called Kuruvithurai, an hour’s drive from Madurai. My husband and I drove on a narrow well-paved road cleaving through rice fields and coconut farms, until we came to a dirt track veering towards the river – there was no signage. We turned right, and within a minute came to the Sitranai. It was twilight and the granite glowed a pale peach in the rays of the setting sun. The massive dam arced across the river, the water cascading down it sides. There were people bathing in the foaming cascades while small white birds hovered over the water, searching for fish.

The dam’s position (it has been cleverly built in a place where the river takes a sharp turn) and design help with both functionality and avoiding maintenance.

The cunning positioning and shape of the Sitranai – Google Earth

The cunning positioning and shape of the Sitranai – Google Earth

When I asked Dr Srinivas Veeravalli of IIT Delhi, who, along with his student, Dr Chitra Krishnan, has studied ancient water works, on how the dam worked, he told me, “When the river takes a bend a radial pressure gradient is set up to provide the required centripetal force. Near the bottom of the river the velocities are much lower, and the pressure gradient causes a radially inward secondary flow [which] carries silt towards the inner bank. (For completeness there is a radially outward secondary flow at the surface.) That is why the canal system is relatively free of silt. In a flood situation, since the anicut is built at an angle to the main flow, it allows the flow to pass over it at higher velocities (compared to a weir built straight across the river) and hence the depth of the river is relatively low, thereby reducing the damage.”

Simply put, ancient Tamil engineers exploited the natural water dynamics of the site to keep the canal system free of silt, manage seasonality and reduce wear and tear of the dam. In other words, they worked with water’s nature – very different from later British constructions, which were based on a far shallower (pun unintended) understanding of local hydrology and sediment mechanisms. The angle also means the force of the incoming water is lower as it strikes at angle rather than full on – meaning the dam is long lasting. The granite dame has stood the test of time – it was built in the 8th century or even earlier, as a 12th century inscription in a nearby temple says.

Sitranai at low flow time (C) SCI

To repeat, the dam understands and works with the seasonality of the Vaigai’s water: during low flow times, water is channelled by the dam into the tank system that supports irrigation around Madurai. During high flow, or floods, water passes over the dam into the main trunk of the river. That understanding of India’s water and a philosophy of trying to work with water (as opposed to trying to reshape it) led to the wealth of ancient Tamil kingdoms as showcased in Ponniyin Selvan. That understanding, and importantly that philosophy of working with nature is missing today, leading us to crisis.

"A fortnight after the Bengaluru Floods. Will it happen again? Yes, most likely."

Published : SEP 21, 2022

Let’s go deeper and ask (a) Is this bout of flooding unusual? (b) Who encroached – were all the motivations the same? (c) What was/should be done about it? (i) Should we Noida-tower the crap out of all encroachers – JCB-Justice, so to speak?, (ii) Or should this move through the court system follow due process, delay-be-damned and (iii) what about compensation – should the poor maid who lives in a shack next to a high rise tower be relocated to a far away neighbourhood and lose two (or more) hours to commute each way – more pertinently, even if she were relocated, would she stay relocated, or would she move back?

Lastly, what next? Quite a few questions, so let us begin:

Is this Flooding Unusual?

There is little hard data to show the level of impact – in terms of extent of property damage (comparable across floods etc), but we can check two parameters: (a) the level of rainfall, and (b) the search interest.

Level of Rainfall

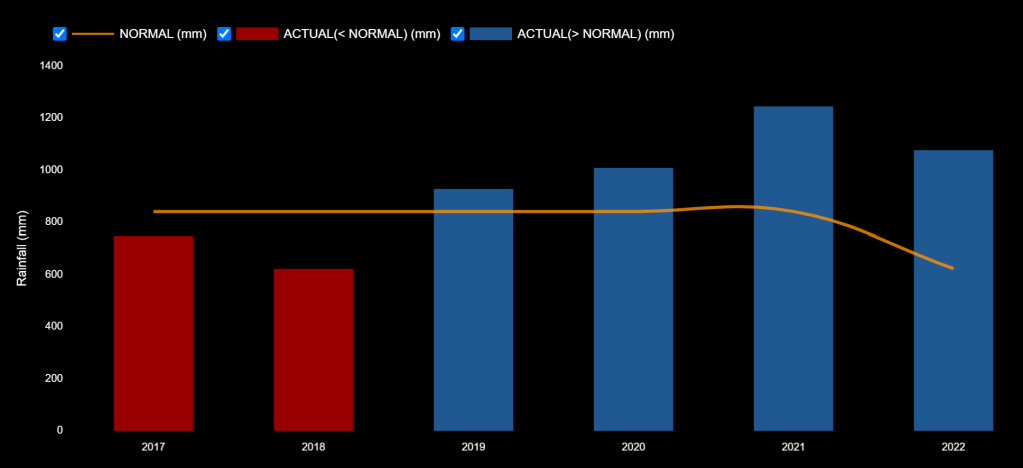

High Rainfall events in Bengaluru District, source: WRIS

High Rainfall events in Bengaluru District, source: WRIS

Looking at the chart above, flooding appears to be quite an annual thing for Bengaluru. Bellandur has flooded (and foamed and caught fire) in the past, as has northern Bengaluru, when some lakes overflowed after heavy rainfall in November 2021. The only thing that makes this episode stand apart is the clustering of flooding within a period of 45 days.

But close readers will point out that this a flawed graph. Rainfall varies quite a bit across a city, and the actual rainfall over a particular neighbourhood, like Mahadevapura, could have been unusually high this time round. Bengaluru had received 131.6 mm of rain on September 5th as per IMD officials (I was unable to find this on an IMD website) – this is more than double the district figure shown in the graph above. But the local data (e.g., rainfall over Mahadevapura over time) was not available easily, nor indeed a time series of such data which would help prioritize which encroachments to clear first. Oh well. Moving on.

But as September high rainfall days in Bengaluru go, Sep 05th was far from the highest…

Source:IMD

Source:IMD

If the rainfall and flooding were not unusual why has this particular flooding event garnered so much global attention?

Level of Search Interest

Using Google Trend data as a proxy, we see that the attention received by the Sep 05 flood event dwarfed any other flood event in Bengaluru’s 5-year past.

Data from Google Trends; Note the region selected is India. The data looks essentially the same if one chooses Karnataka.

Why this flood-fetish? Was this simply schadenfreude? The billionaires who always remained dry and warm, while others had to trudge through the muck had the murky brown water overtake their swanky living rooms and wreck their expensive cars?

Or was there something else? In India, sooner or later, everything comes down to politics. The local elections are around the corner, and the state elections are coming up next year, could this be the reason for the unusually high interest?

The ruling party, BJP’s state general secretary was quoted as saying:

There will be no change in our electoral prospects. See constituency-wise, other than Mahadevapura and Bommanahalli which were largely affected, there was no major impact of rains and floods in other constituencies. did our MLAs in these two constituencies Arvind Limbavali or Satish Reddy create this problem? It (rains) was nature’s fury,” he said, ” the government is working to restore things and no one should politicise it…Let them (Congress) say how much they had cleared during their tenure, we will see how much we did in three years. Ramalinga Reddy himself has admitted they could not do much on clearing encroachments. Who was behind encroachments, gave permissions- whether from the Congress or BJP- let the truth come out. We are ready to debate it factually.”

Moving on.

What about the flood itself? It is unfair to blame the rain alone. Almost all would agree that encroachments lay at the heart of the problem.

Why did this encroachment come about?

There has been so much written about this, often and well, that I will not add to it, except to say, encroachment philosophies vary by who encroached.(a) By government to provide infrastructure and amenities, including siting landfills

For example, the Sampangi tank built by Kempe Gowda was neglected with the advent of piped water early in the 20th century. It was filled up and became the Kanteerava Stadium in 1946. This is a pattern that has repeated across India – the British prioritized centrally provided piped water supply over decentralized community-managed tanks – it suited both their pocket books and their need for control. To achieve this end, they often portrayed tanks as unhealthy, as something dispensable. The latter point was useful to city administrators post-independence to provide convenient land in the heart of the city – the dry tank bed. Easiest way to dry up a tank – encroach its feeder channel.

Tank beds and feeder channels have been officially ‘encroached’ – an oxymoron if there ever was one – for decades. Why are we feigning surprise and moral outrage now? This set the tone for others to imitate.

(b) By builders to cut cost/corners/provide access.

“The rajakaluve here is 40 feet wide but, about 500 metres from here, has been narrowed down to just 10 feet by a big builder,” said Jagadish Reddy, who has lived in Marathahalli for decades. “They laid a slab over it for a road to their complex. We had complained several times and asked them to at least clear the silt under it, but they did not care even for the MLA.”-JAGADISH REDDY TO NEWS LAUNDRY.

Predictably, with less carrying capacity, the feeder drain overflowed with the heavy rains leading to flooding of the surrounding neighbourhood. Advertisement for these “encroacher” properties are carried flamboyantly on the cover of the same newspapers where opinion pages, lamenting the encroachments, are sandwiched in the middle. Many of the encroachments, which are now being cleared, have people protesting that they have received an no-objection certificate to build where they have. The subtext is clear: do it, everyone else is and the chance of you getting caught is small.

(c) By the economically vulnerable/migrants to find housing close to the place of work.

“We moved here 10 years ago”, says a woman in clear Hindi (not Kannada) to a news channel. Many of the slum dwellers act as waste pickers or household help or auto drivers. They are the grease that keeps the city clean and running. They cannot afford a commute as things stand, and therefore they build their own houses on the only vacant land they can find close to their place or work: the tank buffer zone.

Clearing such informal encroachments is likely to be impermanent band-aid: a household help is unlikely to commute 2 hours each way – she will want to stay close to her place of work. The transport infrastructure in most Indian metros will not permit her to live in a ‘legal’ affordable house with a manageable commute. Could vertical building help? Perhaps. Electric mobility will not.

In short, almost everyone in the city encroached or benefitted from such encroachment directly or indirectly (working in a company that encroached/ earned advertising revenue from a building that encroached/ employed a maid who lived in a slum that encroached etc).

So, much like the Delhi Air Pollution crisis, after every flood, there was temporary outrage, a few studies, some clearing and then quietly waiting it out.

Action on the encroachments

This time however, given the media interest and with elections around the corner, the bulldozers are out in earnest.

“By next monsoon, we’ve to clear all pending demolitions… all apartments will be led off, as you saw in Noida. Action to be against officials and builders.-SAID KARNATAKA REVENUE MINISTER, R. ASHOK.”,

What has happened?

“About 11 properties across Yelahanka, West and Mahadevapura zones have been bulldozed, while encroachments in West Zone and KR Puram, Shanthiniketan Layout and Challaghatta were cleared from rajakaluves…However, BBMP officials said only compound walls and gates are being removed, and asked the inmates to vacate in a week’s time, so they can complete the demolition.”-CITIZEN MATTERS, A REGIONAL NEWS PROVIDER.

Not all faced demolition – indeed there have been complaints of favouritism shown towards larger developers. But BBMP has said that they have begun to take action against everyone. The New Indian Express reported Special Commissioner and Mahadevepura Zone-in-charge, Dr KV Trilok Chandra, as saying BBMP would follow the Court’s writ and clear lakes and buffer zones of encroachments as per land survey reports by the revenue department. Countering the charge of favouritism, he reportedly said, “We are first focusing on ‘important ones’. We are ensuring the connectivity to lakes is restored through drains.”

But sometimes clearing encroachment was not straightforward – with clearances being delayed by following due process. Per Citizen Matters, “The BBMP surveyed Bagmane Tech Park on Wednesday and a report is expected to be prepared soon. Bagmane had approached the Lokayukta to restrain the BBMP, but Justice BS Patil only advised both BBMP and Bagmane Development Pvt Ltd to cooperate with each other.”

Meanwhile, The Hindu reported, “Chief Civic Commissioner Tushar Giri Nath said that Bagmane Tech Park had agreed to remove the compound wall which is encroaching the SWD. “However, they have raised the issue that if the wall is removed, it will flood the tech park area. We will take up a survey soon and we will remove encroachments there and at the nearby Puravankara property too,”.

On the other hand, some of the smaller players who claimed they had official ‘permission’ to build where they had were not spared. Per Citizen Matters: “A compound wall built by Sri Chaitanya School in Shantiniketan Layout in Munnekolala was demolished, though there were protests that it had the relevant documents and occupancy certificates. But BBMP officials responded that it was a warning to owners and in a few days they would give notice before more demolitions.”

Having to clear illegal buildings that have received official sanction is going to be a repetitive problem in India’s quest to build climate resilience. There are no easy answers of how to do so.

There are nearly 700 encroachments that have been officially identified on the drains that become essential to ferry away the rainwater and prevent flooding. Experts such as Prof. Ramachandra of IISc say that this identification is a starting point, and more may come about if the exercise were carried out scientifically to understand why water does not drain away.

Until such mapping happens, and the necessary encroachments are cleared, parts of Bengaluru will flood again.

What Next?

Let us acknowledge that clearing encroachments – something that has built up over a century with official sanction, are not easy at all. It will need all hands to push. The best way to move forward is with each community taking ownership of its own neighbourhood and pushing relentlessly not just when floods come to call. To help with this, we need data – after all in a highly contentious issue, knowing the likelihood of a floods, and past occurrences will help. Here, some of the data is available but not accessible. Rainfall varies considerably over a city – the Karnataka State Natural Disaster Management Centre – collects data from several rain gauges from the city. But, when I tried to access a longitudinal rainfall series, or even see how much it rained in various parts of the city on the 5th, I drew a blank. Given the prestigious institutes, both private and public, and the very active civil society in the city, could this data be made accessible, and compelling?

Next, to move forward, could the prodigious IT talent in the city help create a nifty dashboard showing where are the encroachments, what is the status, what is the next step or bottleneck? And could this dashboard be made public to see where and why progress is stalling.

Or do we want to resort to Sir Humphrey?

“They [citizens of a democracy] have a right to be ignorant. Knowledge only means complicity and guilt. Ignorance has a certain Dignity.”-SIR HUMPHREY APPLEBY, YES MINISTER.

What is the alternative? What if status quo did not change? In the world accustomed to WFH, any job that can be Bangalored can also be Salem’d, Madurai’d, Nellore’d or Nagpur’d. At some point, the traffic and the water woes will reach a tipping point, especially as climate change tends to increase the incidence of intense rainfall events. And then the growth might reverse.

It already appears to be happening.

“India is a tech hub for global enterprises, so any disruption here will have a global impact. Bangalore, being the centre of IT, will be no exception to this,” K.S. VISWANATHAN, VICE PRESIDENT OF NASSCOM, QUOTED IN THE MINT. ‘TRAFFIC, WATER SHORTAGES, NOW FLOODS; IS IT THE SLOW DEATH OF BENGALURU, INDIA’S TECH HUB?’ Even before the floods, some business groups including the Outer Ring Road Companies Association (ORRCA) that is led by executives from Intel, Goldman Sachs, Microsoft and Wipro, warned inadequate infrastructure in Bengaluru could encourage companies to leave. “We have been talking about these for years,” Krishna Kumar, general manager of ORRCA, said last week of problems related to Bengaluru’s infrastructure. “We have come to a serious point now and all companies are on the same page.” MINT. ‘TRAFFIC, WATER SHORTAGES, NOW FLOODS; IS IT THE SLOW DEATH OF BENGALURU, INDIA’S TECH HUB?’

"Bengaluru Floods – Why? Why now? Why here?"

Published : SEP 06, 2022

Where has it flooded?

Why has it flooded?

Why here? Why now?

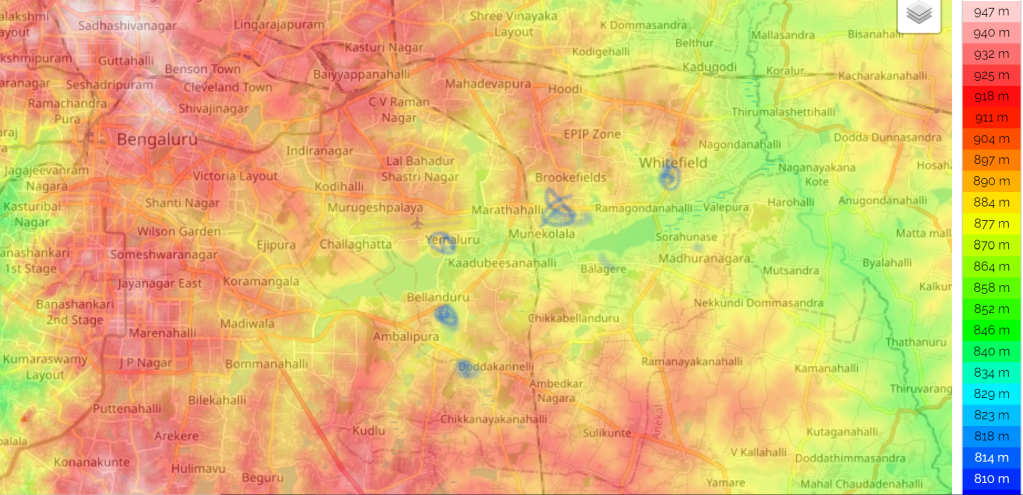

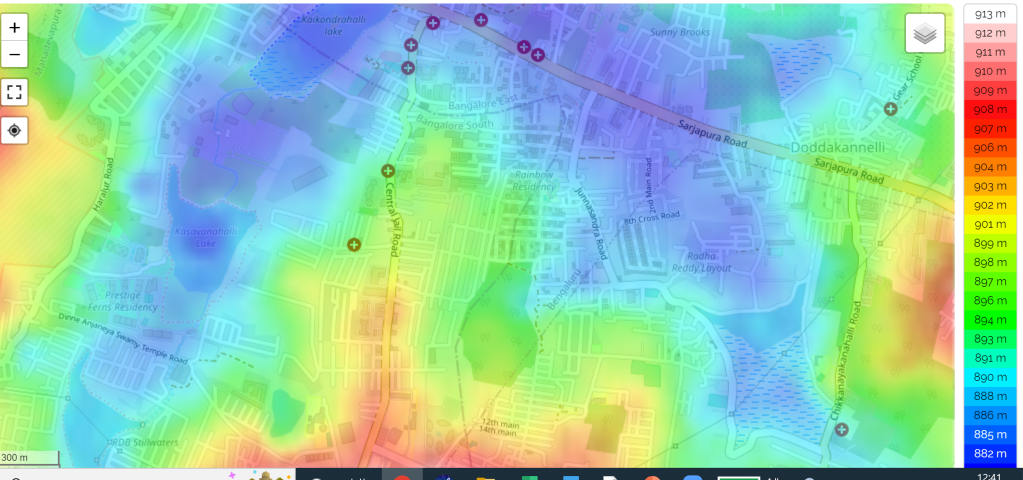

The low-lying areas (green & blue) have flooded first.

Source: https://en-gb.topographic-map.com/maps/lpj1/Bengaluru/; Flooded areas marked out in blue.

Moreover, areas subject to the highest flooding were often the lowest lying within a vicinity. Naturally, water flowed into them.

b. Land-use change – i.e., building over lakes/concretization/ blocking channels

In 1985, most of these neighbourhoods were fields/ lake buffer zones. Today they are densely built up. This creates two problems: a field allows some rainwater to percolate underground. Building over a field with concrete means a greater proportion of rainwater “runs off”. Second, having a lake in a low lying area allows run off water from the surrounding area a place to accumulate. But when you replace lake with house, its the house collects that runoff water and floods.

The biggest casualties in land use change in cities are the connecting channels between lakes. These allow the “excess” water in a neighbourhood/lake to flow into a downstream lake. Sadly in most tank systems in India, Bengaluru included, such channels have been encroached upon/ clogged up with solid waste or overloaded with sewage.

It’s a triple whammy: more runoff, runoff destinations have become houses/offices, and other avenues to channel away run offs have been weakened/eliminated.

There are other micro-level points like roads altering the slope like in the case of Sarjapur Road, adding to the mess.

In 1985, most of these neighbourhoods were fields/ lake buffer zones. Today they are densely built up. This creates two problems: a field allows some rainwater to percolate underground. Building over a field with concrete means a greater proportion of rainwater “runs off”. Second, having a lake in a low lying area allows run off water from the surrounding area a place to accumulate. But when you replace lake with house, its the house collects that runoff water and floods.

The biggest casualties in land use change in cities are the connecting channels between lakes. These allow the “excess” water in a neighbourhood/lake to flow into a downstream lake. Sadly in most tank systems in India, Bengaluru included, such channels have been encroached upon/ clogged up with solid waste or overloaded with sewage.

It’s a triple whammy: more runoff, runoff destinations have become houses/offices, and other avenues to channel away run offs have been weakened/eliminated.

There are other micro-level points like roads altering the slope like in the case of Sarjapur Road, adding to the mess.

c. Lack of maintenance of tanks (desilting/ declogging drains etc)

There are reports of lakes being full in Bengaluru resulting in rains causing overflowing and thus flooding. Two points: Bengaluru has far fewer lakes than it did before. Indeed, a 2015 CAG report says:

"The extent of the lake area varied in different records indicating reduction in lake area over a period of time. This was mainly due to grant of lake area for construction of roads; infrastructure and residential layouts; and change in land use. Also, encroachment of lake area caused choking/blocking of catchment drains, loss of foreshore area and wetland thereby leading to shrinkage in water spread area"

Fewer and smaller lakes, more water and sediment load (including sewage), clogged channels – is it surprising lakes flood?

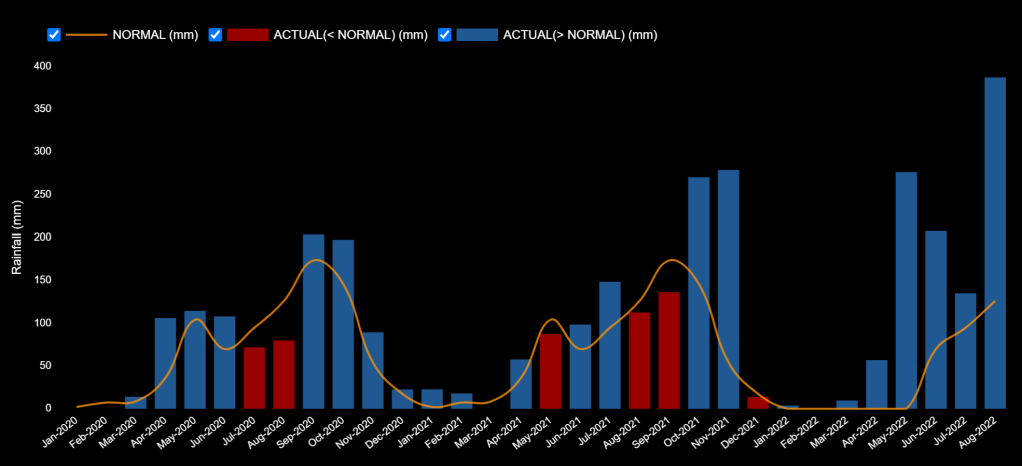

Rainfall

Bengaluru has had a couple of years of good rains filling up lakes and groundwater levels. WRIS

WRIS

While this has been a wetter-than-usual August, Bengaluru’s biggest rain months still lie ahead.

WRIS

WRIS

One reason for this is that this is a La Nina year (wetter-than-usual monsoons for India, generally), and the Madden-Julian Oscillation, a eastward moving “pulse” of rainfall that passes over the tropics. Currently the MJO phase is over the Indian Ocean, bringing rainfall to India. When this moves away, the rains should come down, especially since the Indian Ocean Dipole is currently negative, meaning lower rainfall in India’s winter. More rain appears on its way in the next couple of days…stay safe.

"India@75: Tracing the colonial hand in evolving water tapestry"

Published : AUG 21, 2022

Mridula Ramesh is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute in Madurai and an angel investor.

Within a year of its independence, India turned off a tap. The Indus water partition had left India in possession of the Ferozepur headworks that controlled the Indus water that fed Pakistan’s fields. Friction over Kashmir and water intertwined, and India cut off water supply for Lahore and 5.5% of Pakistani farmland in April 1948. This helped bring Pakistan to the table and a ceasefire soon followed. (Geo)politics is a core thread in India’s water tapestry, as are philosophy, technology and climate.

The geopolitics of the 1950s brought America to the subcontinent, and the US shaped India’s water in three ways. First, America’s Food for Peace programme habituated Indian palates and purses to cheap wheat. Second, the US helped India map and tap into its groundwater. Lastly, the World Bank brokered the Indus Water Treaty (IWT), allowing Pakistan to bypass the proverbial tap. What made India agree? Its monsoon failure in 1957 caused a balance-of-payments crisis. India needed World Bank assistance, which made it willing to compromise on the IWT. The second Indo-Pak war started shortly after the tap was bypassed.

In the mid-1960s, India’s volatile monsoon failed again. As famine loomed large, we paid a steep price for ‘cheap’ American wheat by agreeing to US-dictated policy terms. Desperate to become food independent, the country embarked upon its Green Revolution. Both the Minimum Support Price and the Food Corporation of India were born in this drought, and designed to make India’s farmers grow more food. But why encourage rice and wheat when most Indians ate millets — a grain uniquely suited to India’s volatile rains? Maybe colonial heritage shaped grain-choice. After all, rice and wheat were more suited to global trade (and quick cash) rather than the humbler millet. Technology (borewells to tap into groundwater) helped overcome the volatility of rains — at least for the bigger farmers. Groundwater’s allure lay in its convenience — flip a switch, and water appears. Its danger lies in its invisibility — because we can’t measure subsurface water, we think it endless, until, of course, it disappears. In the 1970s, a flat tariff for borewell electricity was cheapened and then removed. Over time, farmers have made India food secure, but the country paid a price. Today, in a single year, enough groundwater flows away from India’s dry northwest to meet the drinking water needs of India’s largest cities for 13 years! When groundwater runs out, where will that leave food security?

Borewells reshaped cities too. By bringing drinking water to flood plains and the periphery, the borewell overcame the lack of municipal capacity (and planning). Within cities too, water changed. The British declared that tanks (or lakes) harboured infection and should be filled — that they provided empty land in the heart of a city was purely a happy coincidence. Colonially trained bureaucrats continued in that belief and so, India’s city tanks were built over. The giant Long Tank in Chennai, where the Madras Boat club once held its winter regatta, has morphed into one of India’s biggest commercial districts. Few missed the tanks, as groundwater was still available and floods were still uncommon. But the tank-disappearance bomb had been lit, and it has been ticking away since.

Another ticking bomb in India’s shifting water tapestry is deforestation. The British, who saw Indian forests as unsold timber and potential agricultural land, cleared them and encouraged farmers to grow cash crops. But science shows that forest is intrinsic to shaping India’s rains — stabilising land on steep slopes where it rains heavily, reducing monsoonal flooding while increasing summer flow in rivers. Sadly, the British ethos still shapes how we value forests today. Over 60% of the value of forest area to be cleared rests in the timber value of trees, while the forest’s water services are essentially unpriced, making them appear cheaper to clear than they really are. A “water-is-free” ethos, plus the plentiful supply of ground water, retarded water management across the country.

But then, in the late 1980s, a powerful new thread — climate change — entered India’s water tapestry. With oceans hotter and skies warmer, the number of rain days fell, storms and rainfall intensified. Without tanks to absorb the deluge or forests to moderate the flow, floods and landslides became more potent and more commonplace. Dry regions began running out of water — like Alwar in the 1980s, or Chennai in the summer of 2019. To conserve groundwater, Punjab passed a law in 2009 that delayed paddy planting. But that delay shrank the gap between paddy harvest and wheat sowing. The fastest way to clear the fields was to burn them, adding to northern India’s air pollution spike in winter.

In 75 years, India has become wealthier and food secure, but water insecure. The future is frightening with China, sea-level rise and pollution entering the picture, but are we scared enough to see the unique nature of our water and manage it as it desperately needs?

"Mridula Ramesh: "Business leaders exist on a spectrum on 'water/climate awareness"

Published : FEB 20, 2022

Mridula Ramesh is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute in Madurai and an angel investor.

A few business leaders “get” it and are proactive in managing their exposure, some see it as a cost of doing business, and the rest don’t get it - a singularly foolish thing to do in a water-scare country which is rapidly heating up.

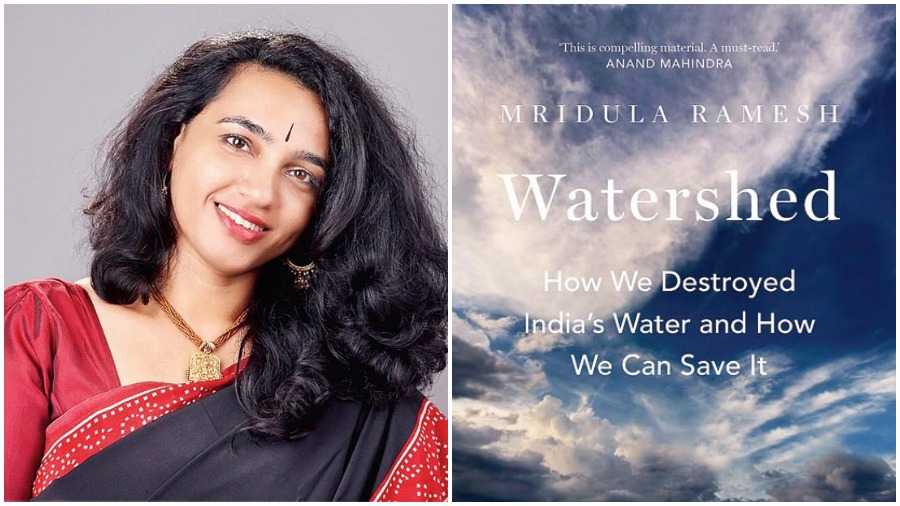

In Watershed: How We Destroyed India's Water and How We Can Save It, author Mridula Ramesh makes a case for water management to avert not just the impending water crisis but also a potential financial crisis brought on by water scarcity. She traces the 4,000-year history of water in India, to contextualise the current problems and offer solutions that might be good for the environment, good for society and good for business.

Ramesh is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute and an angel investor (she has also previously authored The Climate Solution: India’s Climate-Change Crisis and What We Can Do about It).

In an email interview, Ramesh explained how our relationship to water has become dysfunctional, what industry and individuals can do about it, and how she measures the climate impact of the start-ups she invests in.

You've said that our relationship to water has become dysfunctional. Could you give an example?

What lies at the heart of a dysfunctional relationship? A lack of understanding for the other party, and a lack of respect. We don’t understand our water in India – else why we would we grow a crop (paddy) that needs more than 1,240 mm of water in a place that gets between 400 to 600 mm of water (Punjab/Haryana)? The groundwater that bridges this water gap is free – such undervalued groundwater is used with abandon and depleting fast.

Another example is that why would we chop down the forests on slopes that receive metres of rainfall in a few months – after all, without the stabilizing influence of forests, those slopes can and do slide down during the torrential rains.

Based on your research, what are some of the reasons why there isn’t enough urgency about water management – after all, we’ve been reading for years about frothing lakes, flooding cities, and dropping groundwater levels?

There are two levels at which one can answer this question: at the government/political level, as the several examples I have covered in the book clearly show, water provision has been rewarded by voters, but when political leaders have tried to manage water, their efforts have not always been met with political victory.

At the personal level, most of us believe that managing water is not our responsibility (after all, why would you manage something that is free and largely invisible), so we only grapple with it when there is a crisis. The ironic tragedy is that if only we each managed our water, the crisis will bite so much less.

You begin the book by noting how we once had a functional relationship with water – our regional cuisine, water storage systems, etc., all reflected the reality of how much water was available in that region/season. Do you we think some of those traditional methods and knowledge around managing water can be brought back at scale?

The example of what Rajendra Singh has achieved shows some level of scale is possible, but the farmer protest movement shows how powerful the push back will be against any change in crop patterns. So it is possible, but will not be easy.

What is the role of industry here?

Industries, or rather business leaders, exist on a spectrum on “water/climate awareness”. A few “get” it, are pro-active in managing their exposure and impact, and are therefore resilient. Some “tick mark” it – see it as a cost of doing business and move on. The rest don’t get it. This is a singularly foolish thing to do in a water-scare country which is rapidly heating up. Because industry, where it exists, tends to be a major user of water in its immediate locality. Which exposes it to a risk of protests and brand destruction in dry areas. Something one of the world’s iconic brands found out the hard way as I have covered in the book.

If we flip this about, managing water and climate risks are not very difficult to do once we factor them into the business model (and I’m speaking from personal experience here, managing two companies).

You have also talked about the changes businesses need to make to become more sustainable, and how this could affect multinational corporations (MNCs) and small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in very different ways. Is there a solution to this problem?

MNCs will face direct pressure from investors and customers as I have written in the book. SMEs, on the other hand, lack that pressure and are subject to high price pressure which makes them likely to give a short shrift to environmental compliances. One option is for the larger buyers to play a hand-holding and supporting role. The other is for government to have some form of regulation to ensure buyers pay a fair price (and pay promptly) to SMEs. Easier said than done, however.

Is there a startup in this space that you are really excited about.

I won’t name just one, because I have several that I find very cool in this space. One works with farmers to get them higher prices for sustainable practices, including conserving water. They have got a large number of Punjabi farmers to bite. That is one. The other one I have recently invested in treats sewage in Bengaluru to a very high standard and sells it to industries. Both of these herald what I hope will become a larger wave of innovating on water in the future.

You’ve invested in green startups in the past. Could you tell us some of the metrics you use to gauge the impact that a startup might have for water management?

M3 (a cubic meter) of water saved, or added value per m3 of water used. For example, one of the start-ups mentioned in the book, operates micro warehouses in Bihar and Jharkhand and has brought down the loss in stored rice from 25% to 5%. Since this start-up works with 31,000 tonnes of grain, the saved rice saves about 18 million m3 of water a year. Since Bihar has a fairly low rice yield, each tonne of rice saved saves that much more water. The saved water is enough water for 1.5 lakh households a year from the actions of a single company.

You’ve written that one of the key problems in managing the country’s water is the lack of good data. What do you think is missing and what would you propose to improve on this?

Much of the data in my book relies on WRIS, which has made life much easier for water researchers and the general public... The problem lies with the black hole that is water demand. WRIS provides rainfall and groundwater levels at the district level, but is more silent on how much and where and by whom the water is used. This is the gap that needs to be bridged, if we are going to make any headway on managing our demand, and thereby building our resilience. To use an analogy, how do we know if we are financially secure or how to improve our financial security if we only vaguely know how much the neighborhood earns, but don’t know how much we, personally, spend?

You’ve mentioned that climate change policy often talks in terms of carbon emissions but the climate speaks the language of water. What changes would you ideally like to see in this respect?

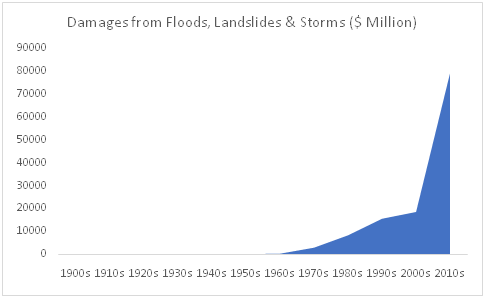

Almost every climate conversation underscores the need to cut emissions. This is important, no doubt. But in doing so, we overlook the reality that we appear to have crossed certain climate thresholds. Just witness the rising cadence of storms and floods in the past few decades.

Why do I say that the climate speaks through water? Consider the rising incidence of storms and the paradoxical (until you understand India’s water) rising incidence of drought. Or the rising incidence of forest fires (caused by less rain and less soil moisture). Or rising sea levels and melting glaciers. In India – arguably one of the most vulnerable countries to this warming – the water voice of the warming climate is shouting loudly. Which only means we need to speak far more than we do today of adaptation, where water takes centre stage.

"Why Climate Change Talk Must Focus on Water, Not Just Stay Obsessed with Carbon"

Published : FEB 13, 2022

Carbon concentrations are so high that the world has warmed quite a bit. And the warmer climate is making itself felt through water.

Nothing works like clarity in getting things done. And the world needs to get down its carbon emissions to keep it habitable for most of us in the not-too-distant future. Naturally, then, most climate conversations revolve around carbon, with political and business leaders jumping onto the Net Zero bandwagon. So why muddy the waters, by talking about, um, water?

Because while the world has been talking about reducing carbon emissions, those emissions themselves have been rising.

Figure 1: Rising Carbon Levels, Scripps CO2 programme

And now, carbon concentrations are so high that the world has warmed quite a bit. And the warmer climate is making itself felt through water. The climate speaks through water, you see. Rising incidence of storms – check. Rising incidence of drought (paradoxical, but understandable once you get water) – check. Rising forest fires (less rain and less soil moisture) – check. Rising sea levels – check. Melting glaciers – check. In India – arguably one of the most vulnerable countries to this warming – the water voice of the warming climate is hollering loudly. Take the damages from just floods and drought – almost all of us have encountered unusually intense rainfall (a finger print of climate change) this past year.

Figure 2: Damages in India from Floods and Storms (EMDAT database)

And despite the talk, it does not appear as though carbon concentrations will fall any time soon. And with that, warming will continue. In fact, even if emissions were to slow down, warming will continue. Climate Action Tracker, an independent website tracking emission pledges by various countries, places likely warming at well above 2 degrees Celsius by 2100. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the gold standard body for climate information, thinks it very likely the world will warm by about 1.6 degrees Celsius from pre-industrial times by mid-century under the most optimistic scenario – i.e., everyone attains climate nirvana and cuts emissions rapidly.

In a more realistic scenario, warming could very likely exceed 2 degrees Celsius by mid-century. If the water is so volatile at 1 degree Celsius warming, imagine how much more menacing it will be when the warming increases. Take a photo on your phone. Now, go to the editing section and start dialling up the contrast. What the warming climate does is increase contrast in the hydrological cycle: its’s akin to what happens to your photograph when you dial up the contrast. Wet regions will get wetter. Intense downpours like what we’ve seen this past year will become more common. And just as the white regions get whiter in a high contrast image, drier regions will become more parched. Think India’s northwest or parts of Tamil Nadu.

Now you see why water must be a larger part of the conversation.

And then there is us. India’s water is already a high contrast photo. We have one of the most geographically varied, seasonal waters in the world. And yet, we do silly things when we ignore water as we have. For example, we destroy what little water storage we have. Mumbai in the early 19th century had reputedly over 3000 tanks and wells – they are all gone. Chennai, Bengaluru, Madurai, so many other cities had tanks which have morphed into neighbourhoods susceptible to flooding as the climate heats up. In another silly move, we have moved to growing climate-inappropriate crops in one of the driest parts of the country. We have done this by dipping into our water savings – our groundwater. Of course, as expenses continually exceed income, our savings run out, which is what is happening around the country.

Our local climate warriors espouse the need for India to cut emissions. She should. But that story might unfold easier, if water was part of the narrative, instead of monomania on carbon. There are plenty of examples, but let me take three. First, coal. So many of India’s coal plants are shut down during summers or in the drought because they don’t have enough water to cool themselves. Their utilisation is so low, that they cease to be profitable. These plants in these locations (polluting, unreliable and unprofitable) make a great case of where India can begin weaning herself off coal, thereby lowering emissions.

Second, take solid waste. One helpmate of flooding is the waste that clogs the drains and the rubble and rubbish choking our waterways and water bodies. Now, managing this waste will reduce flooding and help India adapt to a warmer climate. But in doing so, India stands to create hundreds of thousands of jobs, and cut emissions too! How? India’s solid waste is roughly two-third organic – think food waste. Food waste when dumped in landfills rots and releases methane – a powerful greenhouse gas. Managing the food waste will prevent the food waste (one start-up that I have invested in converts this waste into pressurised biogas to replace LPG. At home, we have a tiny biogas plant that powers one stove).

Third, consider forests. Forests play a critical role in smoothening India’s volatile water. You can see their role by their absence in the Kerala floods. Within forests, consider mangroves. Mangroves play a vital role in protecting our coastline. They ameliorate the effect of storm surges, and are thus powerful climate adaptation warriors. Studies have validated their protective role in the 2004 Tsunami and the 1999 Orissa cyclone. They do this while providing a home to an astonishing variety of species and sequestering many times more carbon than other types of tropical forest. Saving mangrove forests (many are disappearing) can help us adapt to a warmer climate by smoothening the ravages of water even while addressing carbon emissions.

Yes, clarity is important in tackling the climate problem. But when the climate has visibly changed, i.e., as new data emerges, the mandate has to take it into account. And the message from the volatile water is, that managing water must form an important part of the narrative.

Mridula Ramesh is a leading climate and water expert and author of Watershed: How We Destroyed India’s Water and How We Can Save It and The Climate Solution: India’s Climate-Change Crisis and What We Can Do about It. You can follow her @mimiramesh. The views expressed in the article are those of the author and do not represent the stand of this publication. Read all the Latest Opinions here

"Following Chanakya's water neeti"

Published : JAN 30, 2022

One way to work ourselves out of this mess is to adopt a change in perspective. And one way to get a new perspective is to belie the exceptionalism bias, visit our past. -By Mridula Ramesh

We have a tendency to think of ourselves as unique, that our present time is particularly special, and that our challenges are overwhelming and insurmountable and worse than humankind has encountered before. Yes, the climate is changing rapidly now, and CO2 levels are the highest in several million years. Yes, inequality is both obscene and stark. Water consumption is one visible way that manifests—while some frolic in private swimming pools, others rappel down a dried-up well to gather water that oozes out slowly from the earth. One way to work ourselves out of this mess is to adopt a change in perspective. And one way to get a new perspective is to belie the exceptionalism bias, visit our past.

You see, the climate has changed in the past—many times, in fact. And when it has, it has often brought down dynasties—the collapse of the mighty Ming Dynasty of China may have been significantly influenced by the colder climate and poorer harvests in the 16th and 17th centuries. Closer to home, the chaos of 14th century Delhi that saw Sultanates rise and fall like skittles may have a climate footprint to it. Emerging evidence from the study of speleothems (aka stalagmites and stalactites) suggests that the volatility of India’s variable water increased during these episodes of changing climate. Successful leaders understood that the key to withstanding volatility was sound water management. And few gave better water management advice than Chanakya.

Chanakya is popularly considered a minister of Chandragupta Maurya, and the author of the Arthashastra, a manual of statecraft. Pertinently for our story, the Arthashastra provides a fascinating look into the philosophy of water in ancient times. All water belonged to the king, Chanakya decrees, which allowed a single authority to govern water. This is identical to the state of affairs in Singapore or Israel but stands in sharp contrast to that in India today where multiple government departments try to govern India’s water, while the djinni of groundwater makes the notion of governance farcical. Clarity helps management. Anarchy d oes not.

Chanakya also acknowledged the highly seasonal nature of India’s water as is clear from his water pricing. Chanakya’s water price (in contrast to his water fines) were not payable in cash —they were paid through labour or by share of the crop. The former curbed widespread or accidental profligacy—after all, few would squander water that had been laboriously hauled from a well. In agriculture, making the price payable by a share of crops, synchronised price with availability. During periods of drought, when harvests were poor, paying with a share of crop translated into farmers paying less. Contrast this with a fixed, cash tax that the British imposed. This meant during a drought when his crop had failed, a farmer had to borrow to pay tax, a change that embedded money lenders into Indian agriculture.

Chanakya further addressed the importance of progressive pricing of water. So, while everyone paid a water price, the wealthier farmers, who could transport water through mechanical means or through bullock cart, paid a higher water price than those who lifted water from an irrigation source manually. By getting larger users of water to pay more, Chanakya kept addressing inequality front-and-centre in his water philosophy. Contrast that with today, where wealthier farmers enjoy free water (thanks to free electricity to run their borewells), with some even turning into a source of revenue by selling the water they don’t need to neighbouring farmers who cannot afford a borewell. The situation mirrors the inequality in cities—gated communities enjoy manicured lawns watered by free groundwater while those in slums get by on less than a few bucketful’s of water per person per day procured through jostling by the women of the household. The Jal Jeevan mission is a welcome initiative to redress this imbalance.

Lastly, the primary source of irrigation in Chanakya’s time was the tank (which took the volatility and seasonality of India’s water in its stride) and whose administration was decentralised and the community took care of maintenance—in keeping with the varied nature of India’s water. Chanakya valued this maintenance, he gave tax breaks for it!

Today, thanks to climate inertia, warming and its effects are baked in. A highly vulnerable country like India must ramp up its climate resilience, where resilience begins with water management. From Chanakya’s perspective, that translates to a variable, seasonal, progressive price for India’s water, where communities are involved in its management.

Mridula Ramesh is a writer and Founder, Sundaram Climate Institute. You can find her on twitter: @mimiramesh

"'We Have Forgotten Our Water In Every Way Possible'

Published : JAN 19, 2022

Author Mridula Ramesh talks about how, historically, India was aware of how special water was and had devised ways to manage it in a decentralised manner, which is also needed today to solve India's water crisis. ByGovindraj Ethiraj|19 Jan, 2022

Mumbai: "Until water disappeared from our house, it remained invisible to us," said Mridula Ramesh, author of the book, Watershed: How We Destroyed India's Water And How We Can Save It. The book, which also details her own experience when water ran out in her Madurai home in 2013, talks about how at one time in history Indians understood the importance of water and had the awareness to manage it well.

Today, 7% of the Indian population, or 91 million people, are without basic water supply, while nearly 600 million face "high to extreme water stress". India is dependent on the monsoons for rainfall, most of which comes in just 100 hours in a single year, said Ramesh.

Further, with climate change, the supply of water is changing. For instance, a city like Chennai was bereft of water and rainwater for decades, and then it suddenly had a flood. We went from nothing to plenty, and both situations are a problem. On the other hand, the demand for water is rising, especially as India becomes more urbanised.

Ramesh, the founder of Sundaram Climate Institute, which works on waste and water solutions, is also an investor in cleantech start-ups and the executive director of Sundaram Textiles. She is also the author of the book, The Climate Solution: India's Climate Change Crisis and What We Can Do About It. She lives in a net zero-waste house in Madurai. Ramesh spoke to IndiaSpend on how we can manage water better at home, how there is inequality in access to water, and why water is a woman.

Edited excerpts from the interview:

When you ran out of water in your own home, which had never happened before, you used that event to teach yourself about the problem of water scarcity and how to fight back. Let's begin there and then talk about the larger challenge in India and what to do about it. Until water disappeared from our house, it remained invisible to us. This happens to most of us. That is also the premise behind the book. At one time, Indians understood what made water special. One of the statistics you mentioned blew my mind when I started working in this field–that India gets its water in just 100 hours. It's one of the most seasonal waters in the world. The World Resources Institute has compared the seasonality of water among 166 countries. India's water is more seasonal than 163 of them. We understood this once; we had the distributed storage, the awareness, the demand management to cope with it. And then somewhere along the line--the book traces exactly where, how and why water became invisible--we got used to just getting it on the tap. You stop caring and don't see yourself as a part of the problem or the solution. And you just use water, until one day, it runs out, as it did for me.

Your life turns topsy turvy, you run pillar to post to find out where to buy water, is it good quality etc. In my case, that opened the door to a different world because water is best managed in a decentralised fashion. If you can manage demand, it's a very empowering thing to do. Once you try to acknowledge water, try to understand it and say that it's my responsibility, my problem, solving it is not as difficult a problem as it appears to be. It's a grim topic but it's not a hopeless one.

That's a really interesting way to look at it–that it's my problem and not just a problem for the municipal corporation. Walk us through what happened post your water running out. The book tells us how you rolled up your sleeves and set out to find the source of the water and measure it, which was really enlightening. So tell us about that.

I have 15 meters [for water] in our house. We are fully aware of where we use our water. How that helps is that we are able to find a surgical approach to the problem. So many of us, in municipalities and homes, lose so much water to leaks. If you have two meters on either point, you can figure out where you are losing water. And solving it is really inexpensive.

The second thing is that you don't need the same quality of water for all uses. What you flush is different from what you use in the garden. We have three to four qualities of water in our house. It sounds more complex than it is but your neighbourhood plumber will be able to do it. The good thing is that apartment complexes, when they are reaching this day 0 kind of scenario [when you run out of water], they are finding out that it actually makes economic sense for them to do dual plumbing, and use different sources of water for different purposes.

The third thing is…Tamil Nadu was a forerunner in rain water harvesting [asking all public and privately owned buildings to harvest rainwater] but laws remain on paper unless they are evenly implemented. What we found is that 50% of the 2,000 households we spoke to, either didn't have rainwater harvesting or it didn't work the way it should. Many don't even know why they need it. It was like ticking a box to meet the regulatory demand. Rain days are going down in India because of climate change and rainfall is becoming very intense on the days it rains. This is the time when rainwater harvesting is needed more than ever. Again, it's not very difficult or expensive to fix.

Tell us how and why we are facing a water problem today in India? And what is the manifestation of that? As you said, it's become so invisible that some of us don't realise it. And you also mention the income aspect, that in some areas it has become so expensive to buy water.

How visible water is to you depends on where you are as India's water is so geographically varied. It also depends on where you sit on the economic ladder. For the wealthy, water is peripheral–during a flood, they can escape, their homes are dry and their generators run. If you go down, that is, to the middle class, it's a concern of uncertainty, whether the water will enter our homes or will they get water in the drought. And you might think that floods and droughts are different but you have to understand they are the same phenomenon–the intensely volatile and variable water that is India's water. When you go down to the economically vulnerable, their stories are just tragic. That story is repeated in every city in India. You have to beg, struggle, cajole, bribe to get two or three buckets of water.

I would love to be able to give you a certain estimate [on water availability and use], but there is no reliable data. The level of metering is so poor and that's part of the problem. If we can't have good data to agree there is a problem, how are we going to summon the political will to take the kind of decisions to actually solve the problem. There is a huge variation. Some states and municipalities get it, and are going ahead with solutions. Others prefer to live in a black hole. An often quoted statistic, and one I have used in my book, is that India will be unable to meet half its water demand in 2030. In 2021, there are parts of India that are living in day 0. In the summer, they are not able to meet water demand. Factories are shutting down because there isn't enough water.

How did we get here? There were 4,000 tanks in Mumbai and similarly in many other cities in the country which were used to store water. They would not only be useful when there was flooding but they were repositories of water when you would need them. You have also delved into this history in the book, please tell us more about that.

If you look at the history, say the Indus Valley Civilisation. There is a fascinating set of studies, also quoted in my book, in which archeo-botanists looked at hundreds of seed samples from across the Indus Valley settlements over time to know what and where the farmers grew their crops. They found that in places which had relatively more water, river water and melted snow, they grew water profligate crops, and even traces of rice have been found there. But in places, like Gujarat, where there was less water and they relied on seasonal rain, and there is less than 500 mm of rain even today, the farmers made-do with millets. And over time their crops were changed to keep pace with water availability. Chanakya talks so eloquently about water–not only about a water price but variable and progressive water pricing, where the rich farmers pay more, especially when they use technology to access water.

There are two elements, that water shapes cities, and water shapes crops. The British came and said, no, human engineering can overcome water variability. I have spoken about the Punjab Canal Colonies [in my book] and how they taught farmers over time that you can grow whatever crops you want, and the canals will bring the water in and the railroads will truck the water out and the local water availability doesn't matter. Then you come to Indian cities, such as Pataliputra, that were shaped by water. They were usually close to a perennial water source and they respected water.

British cities, like Kolkata, located in a cyclone-prone zone, and Chennai, no perennial river, and then the engineering would get water to the doorstep. But then you fast forward, the British leave, droughts make Indian leaders very keen to become food independent and then comes the lure of the green revolution. The problem there is that you are focusing on crops like wheat and rice in places that didn't grow them. And then you don't put a price on water. India always had a price for water, payable in kind. Once you pay in kind, you are automatically adjusting for seasonality. So when there is a drought you pay less. Paying cash was a change that again came with the British, and then competitive populism crept through in the 60s, and the price of water became flat [without adjusting for seasonality], and then that price was taken away. So water became invisible. There was this huge underground largesse that seemed infinite.

You have spoken about the need to focus on the farm sector when we talk about water consumption. We have seen in the last couple years how growing sugarcane is disproportionate to the water it consumes and takes from other uses, including drinking water. Tell us how bad it is and how we should focus our attention there.

I won't fully agree that it's only the farm sector which we should focus on. I am flipping it around and saying we are responsible for our own water. So sure, if you are in the farm sector, or farm-adjacent, we can focus on that, But cities and businesses are equally vulnerable. We are not going to solve India's water crisis by focusing only on farms, we need to focus on cities and industries too. Having said that, I think the past year and all the things that have happened, it's taught us that policy may not help much.

Let's take Punjab, for example. I think everyone acknowledges that we need a change of cropping patterns. If we grow sugarcane, we need to grow it more efficiently. If we grow rice, in what is almost an arid land, we should grow it more efficiently. But what is more important is that we can't expect the change to happen at the farmer's end. If you can start it at the demand end…I give the example of the egg campaign, [which asked Indians to incorporate eggs in their diet as a good source of nutrition]. You give it [crops] an extensive marketing push, and then hand-holding is what has worked to make people more efficient in growing whichever crop it is. So demand and some degree of hand-holding, again, decentralised.

In 150 years, we have gone from 250 million people eating millets to 1.3 billion eating rice and wheat and that itself is a big determiner of how water is consumed.

Right, and we are growing wheat and rice in the driest parts of the country. We are not growing it in places which get metres of rain in a matter of months, we are growing it in places which get 500-700 mm of rain. Rice needs double that, let alone wheat. Nothing else to me said dramatically, that we have forgotten our water in every way possible. This really started with the procurement policies and was shaped by a drought. Someone said this to me that we started this when we were water secure and food insecure. Now we are trying to use the same horse to get us forward when we are food secure and water insecure. Something has to change but the change has to come from the demand end.

I will give you one ray of hope. There is a startup where I will invest soon. It works with more than 3,000 farmers in Punjab through a local NGO. They put meters to measure water and say that if you are able to bring down the water you use, I can give you a sustainable tag, which gives a premium for your rice, and you can export it at a premium. Small ray of hope. Like how organic milk fetches a premium. But all the organic, sustainable, natural, has to be humanised because done wrong it can be a disaster.

One thing you have spoken about and I would like you to elaborate on is the impact of water or its scarcity on gender. Is that another invisible challenge?

I think it is. Water is female, and that is what I call it in the book, because the women are responsible for gathering water. It's very easy when you live in an apartment and you turn on the tap and water flows in. In our study, most people get water two-three times a week for a few hours a day. In the summers and during El Nino years, which are drought years, they get water once in four days, in the middle of the night for a couple of hours. So they need to always be on alert. So imagine you sleep at midnight, at 2am you have to get up and rush, push, get however much water you can get. The kind of rationing we saw when water was short was sickening. Any kind of health impact of that again fell on the woman because she was taking care of the people in her house.

We are also waking up to the effects of less sleep. So if women are taking a hit to their sleep, they become less desirable employees. India's urban work force participation, Tamil Nadu's urban workforce participation, is less than Saudi Arabia's. This is just stark. Water is not the only or primary reason for this, but it certainly is something to think about. In a story I read about the Vaitarna dam that supplies Bombay with its water, there is a village, one km from the dam, where the water scarcity is so intense that women rappel down a well, wait for water to ooze out and then gather it.

You've spoken about the problem and you've spoken about how we can save it. You've spoken about policy and individual innovation. Industry has to resolve its own problems, as do farms and individual people. How optimistic are you of this happening so that we don't see day 0 coming in more and more cities? There was an interesting example you quoted, that Cape Town in South Africa ran out of water in 2018 and they called it day 0, but it only ran out of municipal water while it always had groundwater. In 2019, in Chennai, it ran out of water, it became day 0, but it ran out of both municipal and groundwater.

Our day 0 is much worse. The day 0 in South Africa has political overturns too. But our day 0 is frightening because we are bone dry. But to answer your question, there is hope in fear. I look at how politically resonan it is, and the short answer is not as much as one would like. Therefore, action has to be decentralised. When the pain is highest, people will hopefully do something. When Chennai had its day 0 moment, Madurai also had its day 0 moment. The good thing is people are waking up to the glory of tanks and lakes. Encroachment is taken more seriously by courts and people are not getting a free pass. The rejuvenation of tanks is moving up the priority list.

When we studied 100 tanks as part of our study, we found that if you live next to a functional lake or a tank, then the groundwater is about 200 feet higher than it would otherwise be. If you rejuvenate a dysfunctional lake or a tank, water levels go up, quite substantially. It varies in how effective it was of course. We studied 19 tanks in Madurai. It's helped with both floods and droughts. In other areas, such as changing our crop patterns, we've had less success. Hopefully that should be demand related. Unfortunately some areas will run out of groundwater. One can only hope and pray.

You've spent a chapter talking about a fairly dystopian future. 2030, only eight years away now, is that your cut off for when all goes to sea?

When I tried to look at what might transpire–it's already happening and it's only going to accelerate. I talk about this geoengineering where people try to cool the planet, and you can see that happening. But unfortunately whenever people try that–they are essentially mimicking a volcano erupting. Given the variability of India's water, if you have drought, a few years down the line you will have intense rainfall. And then you will have floods. The kind of floods you will see will make the recent Bombay floods or Chennai floods or any other floods look mild in comparison.

We have forgotten–This has happened before in the past, the climate has changed. There are reports of when famine stalked Delhi, when they were even reports of cannibalism because it was so bone dry. Floods, when it rained so much in Patliputra that one of the crown jewels of the ancient world just got overwhelmed by floods. You've seen it time and again in Indian history, but we've forgotten, which is not a good thing to do. Especially because the climate is warming and we appear to have crossed some climate thresholds.

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@indiaspend.org. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

"‘Watershed’: Time to get water-wise"

Published : JAN 10, 2022

Delhi battles heavy pollution every winter

"Every winter, Indian capital Delhi's toxic air is fuelled by farmers burning crop stubble. But the fires don't stop. Why? The answer lies in water, writes climate expert Mridula Ramesh.

India loses an estimated $95bn (£70bn) to air pollution every year.

From mid-March to mid-October, when Delhi's air quality varies from good to moderate to unhealthy for sensitive groups, chatter on air pollution and its causes is muted.

But then comes winter. Pollution in any city mixes vertically in the atmosphere, and the height at which this happens shrinks by more than half in the winter, raising the concentration of pollution. Two new sources also enter the mix. By the end of October, when the rains have ceased, the winds begin to blow in from the northwest, carrying fumes from burning fields. Then there is the Diwali, the popular festival lights, where millions burst fire crackers to celebrate.

Both of these play a large role in the spike in pollution. In the first week of November 2021, when Delhi's air quality went beyond hazardous, stubble burning accounted for 42% of the city's PM2.5 levels - these are tiny particles that can enter the lungs.

Governments have banned the practice, imposed fines and even suggested alternate uses for the straw and other crop residue. But farmers continue to burn stubble. Why?

Why crop burning continues to smother north India

How a food crisis led to Delhi’s foul smog

Think of the fields that are on fire. They get only between 500-700mm (19-27 in) of rainfall a year. Yet, many of these fields grow a dual crop of paddy and wheat. Paddy alone needs about 1,240mm (48.8 in) of rainfall each year, and so, farmers use groundwater to bridge the gap.

The northern states of Punjab and Haryana, which grow large amounts of paddy, together take out roughly 48 billion cubic metres (bcm) of groundwater a year, which is not much less than India's overall annual municipal water requirement: 56bcm. As a result, groundwater levels in these states are dropping rapidly. Punjab is expected to run out of groundwater in 20-25 years from 2019, according to an official estimate.

The burning fields is a symptom of the deteriorating relationship between India and its water.

Long ago, farmers grew crops based on locally available water. Tanks, inundation canals and forests helped smoothen the inherent variability of India's tempestuous water.

But in the late 19th Century, the land began to transform as the British wanted to secure India's north-western frontier against possible Russian incursion. They built canals connecting the rivers of Punjab, bringing water to a dry land. They cut down forests, feeding the wood to railways that could cart produce from the freshly watered fields. And they imposed a fixed tax payable in cash that made farmers eager to grow crops that could be sold easily. These changes made farmers believe that water could be shaped, irrespective of local sources - a crucial change in thinking that is biting us today.

After independence from the British in 1947, repeated droughts made the Indian government succumb to the lure of the "green revolution".

Until then, rice, a water-hungry crop, was a marginal crop in Punjab. It was grown on less than 7% of the fields. But beginning in the early 1960s, paddy cultivation was encouraged by showing farmers how to cheaply and conveniently tap into a new, seemingly-endless source of water that lay underground.

Why I switched to eating grandma's food

Pollution in Delhi homes worse than outdoors - study

The flat power tariffs to run borewells were cheapened and finally not paid - removing any incentive to conserve water. Water did not need to be managed, farmers were taught, only extracted. In the heady first years of the revolution, fields began to churn out paddy and wheat, and India became food-secure. But after a couple of decades, the water began to sputter.

To conserve groundwater, a 2009 law forbade farmers from sowing and transplanting paddy before a pre-determined date based on the onset of the monsoon. The aim was to make the borewells run less in the peak summer months.

But the delay in paddy planting shrunk the gap between the paddy harvest and sowing of wheat. And the quickest way to clear the fields was to burn them, giving rise to the smoky plumes that add to northern India's air pollution.

So, the toxic smog is but a visible symbol of India's trainwreck of a relationship with its water.

Paddy cultivation is drying up India's groundwater

Paddy cultivation is drying up India's groundwater

o tackle this problem, Indians need to respect their water again - a tall ask after decades of neglect.

Take people's choices in food and crops. A century ago, most Indians ate the hardy millet, which could withstand the vicissitudes of India's water. Today, there are far more Indians, and they eat rice and wheat rotis (flatbreads), making millets an unappealing crop for farmers to grow.

And pricing water, directly or through electricity that powers the borewells, is seen as political suicide. Meanwhile, as air quality improves from hazardous to (very) unhealthy, people, courts and political leaders have moved on - at least until next November.

But the time bomb - of depleting groundwater - ticks on. Once that runs out, the November air might be cleaner.

But what will India do about food?

Mridula Ramesh is a leading climate and water expert and author of Watershed: How We Destroyed India's Water and How We Can Save It and The Climate Solution: India's Climate-Change Crisis and What We Can Do about It.

"‘Watershed’: Time to get water-wise"

Published : JAN 09, 2022

Sabita Singh Kaushal Today, water is a word of disquiet, laced with apprehension, foreboding and uncertainty. Heavy rains translate into less water, swift floods follow droughts, plummeting groundwater equals water-rich crops; all these and more ceaseless assaults of water-related news recur in our lives, again and again. The waters are shifting, and Mridula Ramesh’s new book, ‘Watershed: How we destroyed India’s water and how can we save it’, delves deep into this seemingly tectonic shift to the waterscape around us.

Ramesh is the author of the new book, Watershed: How We Destroyed India’s Water and How We Can Save It. She is founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, which focuses on waste and water solutions.

At some level, we all seem to sense this not-so-subtle change, but are somehow unable to put our finger on the right spot. This book takes us through a kaleidoscope of the nation’s fluctuating water resources, clamouring demands, the yearnings and the complexity that shape and fulfil our collective and individual water needs. Stitching together water stories from ancient India to modern urban cities, it traverses a journey that is both insightful and thought-provoking.

From the prosperous Pataliputra protected and enriched by its rivers, to medieval Delhi reshaped and framed by water, till present-day Chennai’s lost water connect, historical anecdotes make it an interesting read. It tells of how Israel, a global leader in water management, resonates India’s famed strategist Chanakya’s concept of how ‘all water belongs to the state/king’.

Arthashastra decrees that during that period, all water was highly valued (fine for urinating in a water reservoir was twice that of doing the same at a holy site) and fairly priced, where everyone paid, but the rich paid more. Wealthier farmers who could afford to lift water mechanically into channels were taxed 1/3rd of the produce, while those who manually transported water paid only 1/5th of the produce as tax.

It details how Punjab’s canal system, ‘colonial state’s greatest achievement’, was not simply an agricultural incentive, but represented ‘a hard-nosed, highly profitable investment’ for the British Raj that helped their ‘control, profit and colonise’ intent effectively. In the same state, it explains how free power has translated into groundwater abuse, with over 14 lakh borewells dug (till 2015). Rainfall is not enough for the Punjab farmer, s/he digs deep into the earth and mines groundwater to fulfill the need for a twin crop pattern of paddy and wheat. And, the farming community now finds it nearly impossible to break out of this powerful addiction. Why is that so, even though the farmer realises that the depleted groundwater and soil in the farm serve up as collateral damage?