Sundaram Climate Institute (P) Limited

In the Press

2020

Farms Acts necessary for Green Revolution 2.0; transparency, income support, incentives and communication are key

Tank tourism can help build water resilience in Indian cities; being local, outdoors and socially-distanced make it timely

"Farms Acts necessary for Green Revolution 2.0; transparency, income support, incentives and communication are key"

Published : DEC 23, 2020

India's Farm Acts are a much needed step to get us to Green Revolution 2.0, which in turn will ensure food security at an environmentally appropriate cost. But the laws need transparency, appropriate incentives, and good communication to happen right.

A farmer sits amid wheat fields. Image for representation only, courtesy Aamir Mohd Khan via Pixabay

‘Perspective’. The origin of the word deals with the science of optics, slowly coming to signify one’s ‘mental outlook over time’. It’s doubtful if one can gain much perspective from a tweet, or a WhatsApp forward — the preferred purveyors of news today.

Which bring me to the farm laws, where the lines are drawn, with one side saying, “the farm laws enslave farmers to corporate interests’, while the other side declares, “farmers have been liberated”. As always, there is some truth in both, which requires us to dig deeper. For background on the laws themselves, check out the excellent overview by IDR here. For the legal angle, please read here and here. This article will examine why these laws are so desperately needed.

The Need to Remain Food Secure

Over the past couple of years, writing a book on India’s water has helped me develop perspective. Above all, if we want to maintain our independence, it is imperative to maintain domestic food security, especially now, as the climate warms. There can be no argument around that. Our famines should be proof enough, of what can happen if we don’t. For those who cannot wrap their minds around the possibility of famine, consider the geopolitical angle. Consider how India’s policy has been held to ransom when the rains failed. A bad drought, coupled with a balance-of-payments crisis, weakened India’s position on the Indus Water Treaty in 1957-58; while the back-to-back droughts of 1965-66 saw the US, whose PL-480 wheat was both alluring and addictive, holding India to a humiliating ship-to-mouth existence, and dictating terms that were not always in India’s long term interests.

As the climate warms, without effective adaptation, crop yields will fall. With food, atmanirbhar is unequivocally, a good aim. I am not against trade; I’m merely saying, especially in food, let us trade from a position of strength. Our current atmanirbharta in food owes much to Punjabi farmers. To understand why, let us rewind to the 1960s, where India needed to import rice and wheat, which the populace’s palates had become accustomed to. The Green Revolution, where Punjabi farmers led the charge, saw India slowly and surely become food independent.

Figure 1: India Net Imports of Paddy & Wheat, 2010s refers to period from 2011-2018. Source: FAO.

The Green Revolution was incentivised by the procurement policies of Centre and state, including the MSP regime, and the efforts of our farmers and agricultural universities, especially the Punjabi and Haryanvi farmer. We owe them. However, it would be a mistake now to substitute forbearance for gratitude.

Huh? Come again?

The need for Green Revolution 2.0

The Green Revolution 1.0, relying on underground water, got us here. In a warming climate, Green Revolution 1.0 will only worsen our vulnerabilities and stress our water faultlines, failing to carry us into the future securely. Why?

First, water. Mined from deep underground, this water is embedded in the rice and wheat grown in relatively dry Punjab and Haryana, which then flows as a virtual river to the rest of India. How big is this river? Just consider the wheat and rice bought by the Food Corporation of India from Punjab and Haryana. The water embedded in that procurement alone was about 59 billion cubic metres in 2017-18. That’s about a tenth of India’s overall annual agricultural water demand. Importantly, this river uses up substantial amounts of Punjab and Haryana’s groundwater. There is a limit we are approaching here.

A financial analogy may make this clearer: if you were to spend Rs 2 for every rupee you earned, how long will your bank account last, especially if you are not wealthy to begin with? The latest report by the Central Ground Water Board estimates that groundwater up to the levels of 100 metres below ground level will be exhausted in the next 10 years, while groundwater up to 20-25 metres will run out in 20-25 years. India must look to other states to secure her future food security.

Within Punjab and Haryana, improved yields would help, or a price on the electricity used to power the borewells that suck out the water. While Punjab has the highest rice yield in the country, it has stagnated for a while now. With Punjab farmers profiting at the current price, incentives to improve are muted. Any attempt to price electricity has been stillborn. There is currently an initiative, Pani Bachao Paise Kamao, underfoot in Punjab with the support of the World Bank and J-PAL giving farmers cash incentives for conserving electricity units, and by extension, water. While the results from the pilot were encouraging, results from Phase II have been less promising with far fewer farmers signing up for the scheme. The cash, it appears, was perhaps not seen as worth the effort of conserving this free water. In the midst of protests, groundwater water levels in dry Punjab and Haryana fall as the virtual river snakes its way across India.

The second milestone signalling the end of the road, is air. Recently, the Punjab Remote Sensing Centre reported more than 76,000 incidents of stubble burning between 21 September and 24 November, 2020, the highest in years. Both, the incidence of stubble burning and the share of stubble burning in Delhi-NCR’s pollution, peaked in the first week of November. The Hindu quoted an official from the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), as saying, “It was a bumper harvest this year, so the amount of crop residue was also large. Also, it was a cloud-free season as compared to last year. The biomass was drier and prone to burning… It also appears that the farmers are not willing to cooperate. There could be anger over farm Bills.”

Even those of us far removed from the National Capital Region knew of friends with COVID, and saw frantic messages on WhatsApp groups with pleas for help for a hospital bed for a loved one. Air Pollution plays a role in COVID-19 morbidity, though the mechanics are less well understood. How long can the burning fields persist?

There is a desperate need to change. What’s stopping this? Why are yields stagnating; why is the twin crop culture so enmeshed? Why are the fields still burning? Why isn’t the FCI procuring from other states as aggressively?

Farmers protest in Hisar, Haryana. PTI/File Photo

The need to break an unholy addiction

Punjab and Haryana are addicted to the Rice-Wheat culture. The state’s finances depend on the Mandi tax, and the Arthiyas (commission agents), depend on the 2.5 percent they get. Farmers are unwilling to risk trying to sell outside APMC yards — after all, if it ain’t broke, why fix it? The Food Corporation of India favours Punjab and Haryana because of their excellent procurement machinery, as buying in bulk from other states is nowhere as easy.

Enter the Farm Acts. The catalyst for these was, interestingly, the COVID lockdown. During the lockdown, to prevent congregation at the market yards, or mandis, the APMC act was suspended. But procurement went on unabated. As Professor Ashok Gulati said in a recent interview, “Farmers did not lose at that time in terms of selling their wheat and rice, tell me if anyone in Punjab sold their produce below MSP …39 million tonnes of wheat were procured, which was never done earlier in the country”. Encouraged, the government passed an ordinance and subsequently an Act.

Now, farmers, if they wished, could choose to sell outside the APMC yards to whomsoever they desired. The law does not suspend APMC yards in any way. Essentially, this Act was aimed at increasing competition amongst buyers, thereby hoping to improve price discovery and widen crop choice, thus hopefully providing higher incomes to farmers. However, by doing so, it may weaken APMC yards that are doing a bad job. Is that a bad thing?

Then came the Contract Farming Act and changes to the Essential Commodities Act, to encourage private investment in agriculture. Why? In states where infrastructure was less developed, private investment in storage and market infrastructure could potentially level the playing field. This second part is key: Punjab, has excellent agricultural marketing infrastructure, with a regulated market every 100 square kilometres or so; the situation is far worse in many other parts of the country: with one regulated market serving over 11,000 square kilometres in Meghalaya, or one serving over 2,300 square kilometres in Orissa. Private investment could make a difference, especially now when a clutch of Agritech start-ups are straining at their leashes to enter this sector. The sector is red-hot, and these laws, if done right, can accomplish what Ola or Uber did for urban transport, or what Swiggy and Zomato did for restaurants.

The need to communicate better

Every change has losers. The clear losers here are the state governments who stand to lose the Mandi tax, and the Arthiyas, who could lose their 2.5 percent commission. They stand to lose what has been, in essence, a guaranteed annuity of thousands of crores. That explains the protests, and why it is centred in Punjab and Haryana. Yes, Punjab and Haryana have developed great agricultural markets, but at what cost (water/air), and for how long can it last?

Other losers include the powerful traders, who have thus far enjoyed a large spread over the farm gate price. Why are farmers seen to be protesting? Well, the answer is that there is a tremendous diversity in India’s farmers — the less-efficient amongst the larger farmers, who would be doing very well in the current regime, are naturally wrathful at this potential influx of competition. In some parts, there may be warranted fear based on past experiences with private parties or local government. Lastly, smaller farmers, who historically have been exploited, are — justifiably — traditionally suspicious. In the absence of effective communication, their presence in protests could come about by effective fear mongering. Which makes communication of the “why”, the “what”, and the “what not”, and the “how” of these acts so critical. When one does a quick scan of Twitter and WhatsApp, one discovers there is quite a bit of fluff out there, on every side. It’s surprising then, that a government which went overboard on communication during the lockdown, missed a trick on communicating a law that affects more Indians than did the lockdown. This is definitely one area of improvement. Communicate to the farmer at his/her doorstep, in his/her language, through one of his/her own.

Farmers at work in Sangrur. File photo, for representation only. Image courtesy Sukhcharan Preet

The need for ‘free-er’ and more efficient markets

Which brings me to the second contentious point — the entry of the private sector into farming. News flash: it’s always been there. An overwhelming majority of farmers in India sell today, not at the MSP to the government, but to the private, petty trader in their immediate vicinity.

In December 2014, the government of India released ‘Key Indicators of Situation of Agricultural Households in India’, which confirmed what many knew: only about 10 percent of agricultural households sell their paddy or wheat at the mandi or to a government agency, most report selling to a local private trader or input dealer. The situation is more pathetic as we move away from Punjab and Haryana to other states, and move to smaller farmers. In West Bengal, over 85 percent of farmers owning less than half a hectare sold their paddy to a private trader.

Moreover, government procurement alone cannot guarantee better prices for the farmer or fairer lower prices for the consumer. Take a recent episode in cotton, where an MP, Su Venkatesan, wrote to the Prime Minister about the spread earned by the middlemen, even when a government agency was involved. Private presence can bring benefits — witness the situation in the dairy or poultry industry. There are the many case studies I have covered in my first book, where private presence in agriculture has been of help — in the textile industry, a Public-Private partnership involving over 76,000 farmers in Rajasthan, helped cotton yields improve by 50 percent, and increase farmer incomes.

The real question is the lowering of the spread, or the gap between what the farmer gets for his produce, and what you and I pay for the same produce. The lower that spread or gap, the more efficient the market. Today, in many states, and in many crops, that spread is high. (Note: the green rectangle signifies the range of farmer profitability; the area above the green price line denotes farmers who make a profit at this price.)

" Tank tourism can help build water resilience in Indian cities; being local, outdoors and socially-distanced make it timely"

Published : Nov 31, 2020

Spurring local tourism around our tanks may be just what the doctor ordered.

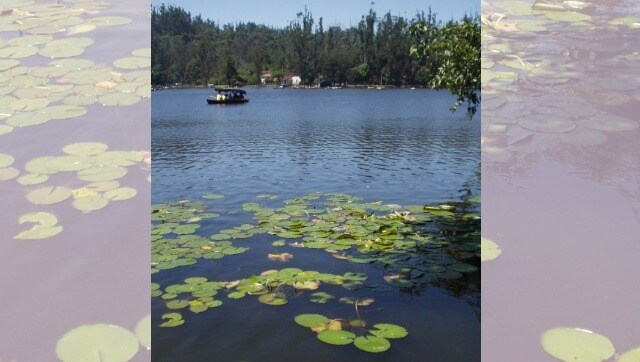

Kodaikanal Lake. Image via Wikimedia Commons

My sister fell off the boat in Kodaikanal, or Kodi as I know it, and they took off my clothes to change her. I had no say in the matter because I was less than a year old at that time. As you can see, the Kodaikanal Lake has been a part of my life for a very, very long time. The corn seller, many of the older boatmen and the horse keepers next to the boat club were friends. Over the years, I have spent countless hours and days around and in the lake, blithely ignorant, until we began to investigate it — the size of the economy supported by the lake.

The community of Kodi Lake

The Kodaikanal Lake is a manmade lake, created by Vere Henry Levinge, by damming three streams. All images courtesy the author, unless indicated otherwise.

The Kodaikanal Lake is a manmade lake, created by Vere Henry Levinge, by damming three streams. This star-shaped 20+ hectare lake, from the very beginning, had a community at its heart. It kept groundwater levels up, to be sure. But the walking path (and later cycling and motorable road) was a place for one’s morning and evening walk, to meet and chat with friends. Trees around the lake provided beauty, improved infiltration, while the smaller, fallen branches created little nooks for water bird to build their nests.

Trees around the lake provided beauty, improved infiltration, while the smaller, fallen branches created little nooks for water bird to build their nests.

The Kodaikanal Boat and Rowing Club was set up in 1891, with a very popular Regatta in May, drawing thousands to witness the races. Yes, I have competed once, and placed second. The more interesting story involves a duck, a friend, and poorly drawn-in oar. Today, the lake is surrounded by three hotels, multiple bungalows, two spiritual retreats, and hundreds of commercial establishments.

The Kodi Lank as a Sustainable Business

Throughout the year, crowds flock to Kodi during the weekends, drawn by the weather, the beauty and, of course, the lake. Business is seasonal, with four phases: peak season (Apr/May), second season (Aug-Dec), off season (Jan-Mar) and monsoon (Jun/Jul). In February 2020, an off season month, we counted 885 commercial establishments around the lake, 70 percent of which were closed at the time of our visit. Many of these stalls would come alive during ‘Season’ time (a colonial moniker), when the roads around the lake would become practically impassable. Of the open establishments, we observed that almost half sold stuff of some sort — sweaters, toys, shells — this translates to additional indirect employment, of course.

More than a third sold food — delicious roasted corn generously slathered with lime, chilli powder and salt being a local speciality. Entertainment — boat riding, horse riding, balloon shooting and cycling — were all on offer. And finally there was hospitality — we counted three large hotels around the lake, including The Carlton, one of the oldest hotels in the town; Sterling Resorts, which courted controversy when it was built on the marshlands that nourished and cleaned the lake waters; and the Green Lake View Resort that was built by demolishing the once delightfully-overgrown house called Sleepy Hollow.

Together, these establishments provided, in a quiet February, 600 lake-side jobs. This is a fairly robust number, with a high degree of confidence, because these were either actually counted or based on interviews with the general managers running the same or similar establishments. The number of lakeside jobs swells to 1,285 in full season (April/May), as rooms are filled and all stalls are running, and then varies between 640-900 jobs for the rest of the year. Only during the monsoon, June/July, are the number of jobs estimated to fall to about 350, as most places shut shop. Taking a weighted average, the lake provides more than 700 direct jobs throughout the year. There are more jobs created in making the stuff sold by the lake, in the factories and in the farms that grow the vegetables and milk made into cheese.

What about additions to the economy?

Because many stalls were informal in nature, their owners were more circumspect in sharing revenue details. Based on data collected from 80 establishments, our model suggested the non-hotel economy of the lake was worth about Rs 46 crore per year. This transforms the lake from being the tableau of memories to a robust economic engine, an SME providing over 700 direct jobs, while replenishing groundwater levels, improving real estate values, improving fitness levels (the walker, rowers and cyclists!) and providing mental bliss (after all, there were two spiritual retreats at the lake side). It makes for one heck of a sustainable business.

Replicating the success

Can we make it even more sustainable? Most of the stalls around the Kodi lake had a municipal power connection. And in shady paths, solar may not work well, and would, moreover require storage as part of the offering, which would make the economics unappealing. Plastic packaging is already banned in Kodaikanal. But ensuring clean power, sustainable packaging choices, and permeable surfaces are things to keep in mind while replicating the Kodi lake’s success in other places. After all, the Kodaikanal lake is 26.5 hectares and there are many lakes this size scattered around our cities. My own Madurai has at least 16 lakes bigger than this in and around the city. Chennai has several. As does Bengaluru, including its infamous flaming and foaming Bellandur lake. Almost every Indian city has at least one or two large lakes that could do with a bit of TLC, an image makeover. However, in their current state, even thinking of these lakes as tourist destinations seems far-fetched. They are like the before-makeover heroine of a coming-of-age movie, waiting for a fairy godmother to wave her wand.

Which brings us to some of the basics for developing ‘Tank Tourism’ in India: First, a water body must, in fact, have water. This is a non-trivial ask as many water bodies tend to be seasonal. However, we do have a great perennial and local water resource — sewage and grey water — which can be treated to feed the lakes. Singapore does, as does Israel. Closer to home, so does Jakkur lake in Bengaluru. In fact, the treated sewage that feeds Jakkur lake is being fought over by the lake and a power plant! Another lake in Bengaluru that has leveraged its sewages is the 26-acre Mahadevapura lake. Here, a consortium of corporates pooled together their CSR funds to invest in a sewage treatment plant that treats a million litres a day of sewage to replenish the lake. The Consortium of DEWATS Dissemination designed the project, and members of civil society came together with this group to bring it to fruition in 2019.

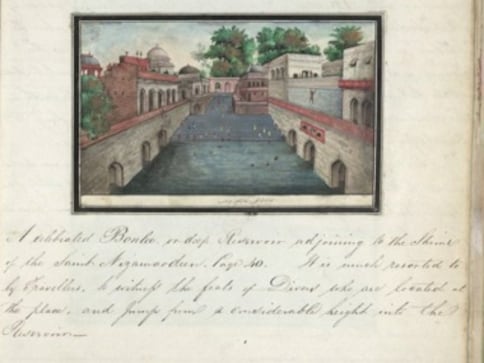

Second, the water cannot smell, and the surroundings must be clean. Offering boating on a flaming lake is unlikely to have a large addressable market. Delhi has a wonderful clutch of baolis, or stepwells, and in a better world, they would be centres of community. Today, many of them are non-trivial to access. When my friends and I went on a detective mission to locate the oldest baoli in Delhi, the Anangtal Baoli dating back to the 10th century A.D., we had to pick our way through a landfill to get there.

The historical Baoli ceases to be a tourist attraction. These are the basics — water and cleanliness. Next, tourists need infrastructure — lighting, dustbins, a walking or cycling track, signage. Ideally, these should recharge the mind, and not be monstrosities of concrete. Thus can we unlock the tank tourism economy, where catering to their needs creates local jobs. In this age of COVID, we all need a little bit of socially distanced outdoor recreation. In this age of climate change, our cities need all the water storage we can muster. In this age of water crisis, we need to treat and reuse every drop of sewage. In the midst of this economic carnage, we need more local jobs. Spurring local tourism around our tanks may be just what the doctor ordered.

The writer is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, cleantech angel investor and author of The Climate Solution — India's Climate Crisis and What We Can Do About It published by Hachette. Follow her work on her website; on Twitter; or write to her at cc@climaction.net.

"Tanks are silver bullet for India's water woes; why they're disappearing, leaving us more vulnerable to a warming climate"

Published : Oct 27, 2020

A warming climate, bringing fewer rain days and more intense rainfall events in its wake, makes the role played by tanks even more critical.

A tank in Tamil Nadu. Image via Wikimedia Commons

Editor's note: This is the first in a two-part series on the critical role of tanks in India's water management system. It draws from Mridula Ramesh's upcoming book on water, to be published in 2021.

Imagine if you received all your annual income in a few days, but still had to make monthly payments — rent, EMIs, school fees, medical bills etc. You would need a place to store your money, wouldn’t you?

For much of India, a large chunk of its rain falls in just 15 days, often in about only 100 hours. This makes water storage and management critical, especially for the somewhat drier regions like Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu or Telangana. The erstwhile rulers of those regions built tanks — essentially lakes — thousands of them. For example, the Kakatiya dynasty, who ruled Telangana 12th to 14tn centuries focussed on tanks, realising the special key water storage held for prosperity. Somehow, in our rapid urbanisation in the past few decades, as house overtook field, we appear to have forgotten this defining facet of India’s rainfall management.

As I have said before, tanks are brilliant. They work in two ways: one, they store rainwater from whichever area they directly drain, and allow the rainwater a chance to percolate into the ground, rather than ‘runoff’. Second, a subset of tanks, called system, or cascading tanks, are connected to a network of other tanks and to the river through canals. These system tanks are the beneficiaries of surplus non-local rainfall. During the southwest monsoon, many peninsular rivers swell with the rain from the Western Ghats, the mountains girding the western coast of India. This surplus water flows from the river through a set of channels to tanks, and as each tank overflows, downstream tanks and smaller satellite ponds, sometimes connected by channels, get filled.

Tanks are an elegant way to spread seasonal rainfall over the year.

To use a financial analogy, system tanks are like (sticky) Foreign Direct Investment that transfer non-local savings into the local economy. Tanks capturing local rainwater are like local savings being channelled into the local economy. A warming climate, bringing fewer rain days (or days where it rains), and more intense rainfall events in its wake, makes the role played by tanks even more critical.

The case of Hyderabad

Take, for instance, what is tragically unfolding in Telangana over the past week. We have two patterns — one of extreme rainfall, and the second of unwise land-use changes. In the first two weeks of October, several districts in Telangana received well above their ‘normal’ rainfall. In the same period, the Hyderabad district received nearly 30 centimetres of rain, almost three times the ‘normal’ amount. Several parts of the city received between 10-20 centimetres of rain in a day. With a warmer climate, such incidences will likely recur.

To blame the hair-raising images of a man being swept away on a road-turned-roaring-river on the climate alone would be unfair, and, perhaps more importantly, unhelpful. Did the intense rainfall translate into the fury we witnessed, because the water was squeezed into a space too small to hold it? Because we had converted lake bed to plot and thence to building, thrown rubble into river and tank, and asked flood waters to share space with torrents of sewage in already encroached and silted stream or river?

To wit, compare the picture of Hyderabad from 1991 to 2016 on these Google Earth images: shrinking the space for water to occupy merely makes it spill, or flood over, during intense rainfall spells.

Why then are so many tanks and lakes disappearing or falling into disrepair?

To answer this, let me come back to Madurai, where I live, and where tanks — until a hundred years ago — held pride of place. If you take a flight over Madurai any time after August, you would not be wrong in thinking that someone had shattered a giant mirror and strewn the shards across the land, because that’s how the thousands of tanks or lakes appear from the sky.

Water management has such a pride of place, that we found over 40 words in Tamil just to speak of water, with several words for a tank or lake — Eri, Kanmai, Kulam, Kuttai, Oorani, to name just a few. Each referred to a particular type of tank, designed largely for a particular purpose. Eri or Kanmai both referred to irrigation tanks, while Oorani referred to a drinking water pond, typically located like planets around a larger Eri or Kanmai. There were names for tanks within temples, tanks meant for livestock — clearly this was an important subject in the days of yore. There were also several roles assigned for water management — Neeraanikar, Neerkatti, Karaiyar, Kuzhathu Kaapalar — for water rotation, operating sluices, for cleaning the tanks, for ensuring there were no encroachments. At Sundaram Climate Institute, we differentiate tanks in terms of functionality. As in relationships, tank functionality spans a spectrum. Highly functional tanks tend to provide tremendous benefits — both in variety and amount — to their immediate community. In our study of 42 rural tanks, we found functional tanks provided more than irrigation access; they provided cash flow — so vital to the rural economy — by enabling fishing, furnishing water for livestock, and, in many tanks, lotuses, which retail between Rs 5-10 for a single bloom. While farmers with better situated land appeared to value water rights highly, landless workers and smaller farmers reported valuing fishing, access to water for cattle, temple and burial rights more. Perceived as equally important were the non-financial benefits: Indeed, some of the smallest tanks were highly functional because the surrounding community thought of them as sacred, and researchers from our team were asked to remove footwear before venturing near the tank. Almost every tank we studied had a temple associated with it, with temple rights seen as an important aspect of the tank benefit ecosystem.

When our team spoke to an old woman grazing goats next to a small pond, she spoke of the pond as a living thing. No form of refuse can be dumped into pond tank, she said, as it is considered as God’s living place and respected. The tank’s god was called “Pattakati Oodaiyan”, and one family, with hereditary rights, lived in a small hut by that pond and was responsible for the maintenance of the pond. The pond, small as it was, provided enough water for the livestock, and for the community. This story too turned melancholic, as stories do. “Earlier we had country fish like iyerameen, koravai meen, keluthi meen,” the woman said, although she could not quite remember when they caught fish last, “Perhaps a few years back.” This year too, they tried placing some fish in the tank, but they died.

Sometimes, the word ‘community’ conjures up a warm and fuzzy image. This, in our experience, is not often the case. There were strong caste dynamics at play in the tank maintenance and access. However, without glossing over the caste and gender equations, we observed that all castes were worse off when a tank became dysfunctional, and the economically vulnerable sections even more so. With that caveat, when a tank provided regular benefits, a community is vested in keeping a tank healthy, and free of encroachments. So what happened to upend this not-quite-idyllic equilibrium?

We found there were three key reasons why tanks tended to die: (a) Centralisation of maintenance, (b) Urbanisation/ Encroachment, and (c) the emergence of new sources of water.

Centralisation

Let us begin with centralisation. The centralisation of tank maintenance has not always been good for tanks, specifically for the fishing ecosystem. One exception appeared to be the MNREGA scheme, which we found played a significant role in desilting local tanks, and strengthening bunds. One farmer spoke of 11 varieties of fish in earlier times, with lifecycles in sync with the rising and falling water levels. This diversity suffered when quantity was prioritised over quality, with the Katla coming to dominate the catch. The problem with larger catches is that it better suits larger bidders, often not associated with the village community. Then, of course, someone may complain of irregularities in process, and a court case is opened. For the bureaucrat responsible for the auction, being asked to appear in court is an unwanted pain in the neck, in the midst of a crowded day, and overflowing inbox. Slowly, fishing auctions fail to take place, or take place surreptitiously, meaning one key benefit to the community falls.

In urban tanks, apart from this hassle, the responsibility for evicting encroachers also moves to a government department. Given that evicting encroachers is anything but an easy affair, one needs time, means, power and single-minded zealousness to ensure success. This is easier to command if one’s livelihood depends largely on the wellbeing of the tank. Less so, if it only one of your many duties, and one you will receive a lot of pain in doing, but little credit. Besides, the motivation to maintain tank ecosystems reduces when new sources of water and employment come up.

New sources

In the end of the 19th century, the Mullaiperiyar dam was built to divert the waters from the river Periyar to the river Vaigai. The Vaigai had always been a non-perennial stream, and the thinking behind the dam was: ‘Why not move some water from the water-rich Periyar to the water-poor Vaigai’ — a sort of redistributive socialism with river water. Even back then, the idea was not new — it had been around for nearly a hundred years, but the tragic famine of 1876 gave it the final push.

By most accounts, this diversion seemed like a good idea — farmers were able to grow more, at least those connected to the system tanks that now received the additional water largesse from the Periyar-fed-Vaigai. Indeed, some parts of Tamil Nadu dedicate their harvest festival to the officer who built the dam, John Pennycuick. But there was a side effect: tanks in the Vaigai basin became less dependable as sources of water, first when the Periyar dam was built, then later when the Vaigai dam was built. This appears to be a non-sequitur, until one realises that when farmers received more water from the Vaigai, they became less interested in maintaining the tanks to eke out water, which makes downstream tanks less dependable.

But what gave the body blow to tanks was the advent of the tube well and the free electricity to power pumps for agricultural use. Slowly and steadily, the importance of tanks in irrigation came down — see the thinning yellow sliver in the graph below:

Net Irrigated Area by source (Directorate of Economics & Statistics, Department of Agriculture and Cooperation, Ministry of Agriculture, Government of India), Statistics Handbook of India

Borewells are usually a rich farmer’s province, the same farmers whose lands lie close to the more important systemic tanks. If they slack on maintenance, because they now have access the free water, the tank ecosystem suffers. Having the borewell also makes them less inclined to guard against encroachments and garbage being dumped into channels feeding downstream tanks. This further reduces the flow of water to the downstream tanks. Lastly, sand mining deepened the river bed, meaning in times of low flow, water could not flow from river to canal, because the water level was lower than the outlet level. All of these translated to tanks becoming an unreliable source of water. Indeed, the percentage of years during which where all the tanks were filled, fell from about 71 percent in the pre-Periyar years to about 33 percent in the period between 1986 to 2001. Naturally, this made farmers less keen on maintenance: Why labour on something that will not allow you to grow another crop or increase your yield?

In cities too, the rise of the borewell heralded the collapse of a civic sense. Why protest about encroachments and tank disappearance, when there were mountains of water available at the flip of a switch under one’s very feet?

Urbanisation and Encroachment

The deadliest blow comes when house or factory overtakes field. When fields with an established right to the tank water transform into housing plots, the new owners of the land lose water rights, and the tank becomes an orphan, ripe for conquest. Typically, the channel is first to fall: we saw this several time in our studied tanks: “The Odai [channel] to the tank from the Periyar river is blocked, earlier it was broad now it has narrowed done because of *** factory,” said many we spoke to.

In cities, this problem was widespread. In the second half of the 20th century, the population of India’s cities exploded. This just meant more and more people were being squeezed into a smaller place.

Population Growth of Major Indian cities, 1901-2011

Indian cities tend to be smaller than other global peers, as a recent Economic Survey on India showed. One reason for this is insufficient infrastructure. Take the case of transport — job opportunities tend to be highest in the centre of cities, where land prices are nose-bleedingly high. To take advantage of the jobs while also living within their means, employees need access to low cost, convenient mass transport. This missing link in Indian cities leaves roads crowded, and the poor living in slums close to their place of work. As a result, India cities are amongst the most land scarce regions in the world — especially within corporation limits.

With the masses pouring into the cities, municipal governments must provide infrastructure — bus depots, schools and such — to cater to their needs. But where would the land come from? Governments like announcements: “XYZ bus terminal will be built this year”. But the legendary, exquisite tortuousness of land acquisition in India makes quick infrastructure building impossible. And that’s where the tanks — once filled with water, the centre of community life, now neglected, choked with waste, and dry — become interesting. This is compounded by the water diversion policy of the irrigation department, which tends to preferentially supply water to those tanks which still have an ayacut (irrigation area) attached to them, above urban tanks. As the urban tanks go dry, they offer inviting, quickly-acquirable, new land in the heart of the city. Tanks are classified as ‘poramboke’ land, which allows the government to divert them for other purposes. Typically, when the tank bed wants to be diverted for other purposes, the concerned officer or Tahsildar makes an announcement that the tank has fallen into disrepair; it is an eyesore choked with waste and a breeding ground for mosquitoes etc.

Why don’t communities in urban environments care about what happens to tanks?

Again, there are several possible explanations. While the groundwater flowed freely, why care? Second is that we are conditioned to think of groundwater and surface water as separate. After all, they are governed separately, so why not think of them the same way. This ‘hydro-schizophrenia’, as Dr Mihir Shah terms it, is one reason we discount the value of tanks — because we don’t realise how tanks, or urban lakes as they have become, recharge the groundwater on which so many of us depend.

The hidden power of tanks

To test if indeed tanks influenced local groundwater levels we studied 36 urban and periurban tanks in Madurai, wherein we estimated groundwater levels at set distances using crowdsourced data from over 3000 persons. Our data gave us this graph that showed tanks did indeed appear to recharge groundwater in their vicinity:

On the left hand side, was a stunning, large rural tank about a 10-minute drive from Madurai — you can see that the groundwater was available at quite shallow depths around the tank. On the right hand side, we see a tank in bad shape, a critical care patient if you will, with both inlet channels and the tank itself encroached upon. Unsurprisingly, it has a marginal impact on local groundwater levels. Clearly all tanks are not the same. But, what, we asked, makes a tank functional? Again, we checked the effect of several factors including size, land use patterns around a tank, urbanisation etc., on groundwater levels to see which were most impactful.

What mattered a great deal for system tanks was the condition of the inlet canal — if it was clogged or upset in any way, that was the end of the tank. For instance, there was a giant tank in our study that was almost always dry despite not being encroached in any way. Desilting that tank, which MNREGA focusses on, would not have helped rejuvenate the tank. The problem lay in the inlet, which, because of a road construction, now lay below the tank bed, with a road traversing between. For standalone tanks, we found an important predictor of functionality was the number of months a tank held water — any water. We also found land use patterns to have a strong impact, with more open and green spaces better helping recharge groundwater more. Importantly, the community was important: when the community spoke of a tank with pride, and protected, the tank tended to be highly functional. Our study helped us come up with a functionality index for a tank, and tank report card, serving the same purpose as a student report card.

This functionality is important, because we found functional tanks kept groundwater levels about 200 feet shallower.

Tanks are silver bullet for Indias water woes why theyre disappearing leaving us more vulnerable to a warming climate

This effect has economic consequences: we found that the average monthly spend on buying water of studied households who lived around a functional Oorani was Rs 100 lower than the average monthly spend on buying water of studied households living around a dysfunctional Oorani. That’s comparable to a free kilogram of rice per month per household.

Sadly, but unsurprisingly, the communities were not making the connection between having a functional tank in their backyard and paying less for water each month. Communities, also, until recently, were not making the connection between a functional tank, and some form of insurance against a changing climate. One way to do this would be to include the many functions of tank ecosystems in our curriculum. What else can we do to strengthen the bond between tank and community in an urban environment? We will see what that is in the next column.

Part 2 — Tank tourism can help build water resilience in Indian cities; being local, outdoors and socially-distanced make it timely

"Coronavirus Outbreak: Four pivotal lessons for the world, from the unfolding pandemic"

Published : Mar 27, 2020

Over the past few weeks, the coronavirus pandemic has taught us four things about ourselves.

This is the concluding segment of a four-part explainer on the coronavirus outbreak. Read parts 1, 2 and 3.

Over the past few weeks, the coronavirus pandemic has taught us four things about ourselves.

1. Governments are capable of strong, quick action.

2. The world remains unequal, with widening inequality.

3. The world has changed; China has changed.

4. Size does not matter. Time and communication does.

Strong, quick action

In January, China put 10+million people under lockdown. At that time, the world said, China is the only one who can do it.

The New York Times, on 22 January 2020, wrote:

“Scale of China’s Wuhan Shutdown Is Believed to Be Without Precedent.”

“In sealing off a city of 11 million people, China is trying to halt a coronavirus outbreak using a tactic with a complicated history of ethical concerns.”

The same NYT, reported a day later that China was ‘essentially penning in more than 35 million residents’, bringing to mind lambs held for slaughter. It was thought that draconian lockdowns were the province of undemocratic countries.

Less than 50 days later, decidedly democratic Italy followed suit, trying to lock down its 60 million citizens in a bid to control the virus. And when that failed, calling the army in to enforce movement restrictions. Liberty, it seems, is not a given.

The Times headline on 15 March, showed how much mental space we had covered in 60 days.

“Spain, on Lockdown, Weighs Liberties Against Containing coronavirus .”

“Empty streets. Shuttered stores. Spain has joined the number of countries struggling to balance public health with freedoms especially prized in a relatively young democracy.”

California – the heart of liberalism in America – went into lockdown mode in the middle of March. There were reports that the police department was using drones to enforce the ban, and convey information to the homeless. If you don’t have a home, where do you stay locked down? New York and Illinois soon followed, asking over 70 million Americans to stay put in their homes. Within days, Britain, which had initially trumped down for herd immunity, changed tack, and locked down. By midnight on 24 March, India’s 1.3 billion were under lockdown for 21 days. There were exceptions, but this scale of lockdown is unprecedented anywhere, ever.

We need no further proof that governments can take quick, strong action, when they perceive the need to be important. We are less than a month into lockdowns in some countries, and a day into lockdown mode in India. How long can we sustain it? These are uncharted waters, and, honestly, I have no clue. Look to the slums – that may be the place unable to bear the strain, and may break first.

The lockdown is predicated on the existence of a vaccine. There is a global race to create a vaccine, with an American vaccine and a Chinese vaccine in Phase I clinical trials. Best estimates say a good candidate is about a year away. In the meantime, as the Northern Hemisphere heads into summer, the Southern Hemisphere is heading into winter, helping the virus spread.

Widening Inequality

This lockdown impacts different groups differently

Gainers – Some 24-7 news channels, WhatsApp, Netflix, medical equipment/mask and other protective equipment/test-kit manufacturers (some of these are providing material/services at subsidised rates, and those cannot be considered gainers), short sellers.

Less impacted – Many information-age companies can work from home. There is a disruption, sure, but work does get done, there is saving of office power bills and transportation expenses, and revenue can be billed (sometimes). The well-to-do are losing money on the stock markets, and in profit, yes. But, this group can afford to take up ‘pursuits’, and enjoy the fresh air.

Impacted – Most of India. Retail. Manufacturing. Cinema. Schools. Religious services. The operators of these outfits are almost certainly looking at a loss this month, or maybe even this quarter. Highly leveraged players within each segment will face survival risk. Workers in this group have some job and wage security, for some time.

Wiped Out – The informal sector, including daily wage earners, beggars. Many of them operate on days. The money lender is not renowned for his forbearance. One other group, that may not elicit much sympathy, is the imprisoned community. Do we set them free or let them be?

One additional point: Most people in India do not get piped water at home. If last year’s data holds good, people, women, wait in lines to collect water. How will lockdown work here? As with climate change, this lockdown too, seems to be increasing inequality.

China

Wuhan is a prosperous Chinese city of 11 million. One reason for how the virus spread across national borders is when tourists from Wuhan visited other countries. China is now buying, not just selling – it’s harder to keep people buying one’s wares and services out. Some of you might remember the Will Smith movie, Independence Day, when America gloriously takes the lead against the aliens invading Earth. America has been too busy to playing catch-up to the virus at home to have much time to help others. They did, however, extend aid to Pakistan.

China did extend aid — officially and unofficially. There were planes of medical supplies and expertise to Italy. Then there was Jack Ma, who has been acting as China’s Unofficial-Ambassador-at-Large, donating and shipping out millions of masks to Africa, Latin America, Europe and South Asia. Interestingly, when pretty much every other country in South Asia was covered, India, reportedly, was not. He tweeted, ‘Go Asia! We will donate emergency supplies (1.8M masks, 210K test kits, 36K protective suits, plus ventilators & thermometers) to Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Laos, Maldives, Mongolia, Myanmar, Nepal, Pakistan & Sri Lanka. Delivering fast is not easy, but we'll get it done!’. Ironically, the Ali Baba foundation tweeted, ‘Through a donation of 500,000 testing kits and 1 million masks, we join hands with Americans in these difficult times.’

Jet Li was saving Will Smith from the aliens! This is an interesting dynamic to watch in the coming days.

There is one more. Two coronavirus epidemics, the SARS epidemic in 2002/2003 and this one, began in earnest in China – both probably from a wet market. Both of these epidemics are caused by RNA viruses. There are about 180 known types of RNA viruses which infect humans, with about two new species added every year. Most RNA viruses are zoonotic – i.e., they came from an animal host. This just means one thing; epidemics like these will recur. The Chinese preference for fresh exotic meat may carry too high a price for the world, in many ways.

Size does not matter, time and clear communication does.

The economic damage from this virus, and from the lockdowns to prevent the virus spread, will be vast. The UN estimated a $1 trillion blow. Stock markets reportedly lost $26 trillion from their February peak. These are big numbers, and every government stands ready to throw fiscal rectitude to the winds when stimulating their economies.

However.

Climate change is a far bigger threat economically, over time. It is expected to shave off trillions from the world’s GDP by 2050, while extreme events cost just the US $312.7 billion in 2017 and $91 billion in 2018. In 2019, weather-related disasters, a fingerprint of a warming climate, cost the world $229 billion in damages alone. In half a decade, using the UN estimate, a warming climate will easily cost the world more in dollars and lives than COVID-19 . Yet, governments have not taken action. Worse, many act in the opposite direction, with the IMF estimating that the subsidies for fossil fuels extends to $5.2 trillion in 2017.

Let’s leave morals and compassion aside – hard to do, since hundreds of millions are affected today. But leave them aside. On economics alone, discounting costs, depending, of course, on the discount rate, acting on climate change makes sense. Yet we haven’t. While we have taken expensive, draconian action to limit the spread of a virus with an average fatality rate of < 1.5 percent for people aged less than 60. Given low testing levels, and the fact that the disease is asymptomatic in so many people, the fatality rate could be even lower.

Why is that?

One possibility is that the slow burn of climate change is psychologically different from the quick blow of the virus. Think of the proverbial frogs in the pot of water set to boil. Time matters.

Another possibility is that there is a clear villain, who everyone hates – the SARS-CoV-2 – in this pandemic. There is overwhelming evidence than burning fossil fuels are the villain in climate change. But not everyone hates them.

Yet another possibility is that the people leading the cry for action are doctors, who are comfortable making clear and compelling disease trajectory predictions, with fatality rates, based on limited data. Compare that with the hedged, unclear calls-for-action in climate change. Enough said.

The writer is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, cleantech angel investor and author of The Climate Solution — India's Climate Crisis and What We Can Do About It published by Hachette. Follow her work on her website; on Twitter; or write to her at cc@climaction.net.

" Coronavirus Outbreak: Aggressive testing, containment in small pockets — what India really needs to combat COVID-19"

Published : Mar 24, 2020

India’s handling of the crisis until now, barring testing, has been hard to fault. By aggressively acting, the hope is for the spread of coronavirus to be curtailed.

This is part 3 of an explainer on the coronavirus pandemic. In part 2, how effectively will policies of travel restrictions and social distancing control the spread?

Fear is the emotion that makes us blind.Usually I go to Shakespeare for inspiration, but this time, it was Stephen King, who perfectly captures what we are feeling.

We are fearful. In the past few months, globally, over 15,000 people have died while trying to combat COVID-19 .

Meanwhile, “CDC estimates that so far this season there have been at least 38 million flu illnesses, 3,90,000 hospitalisations and 23,000 deaths from flu.”

23,000 deaths in one country, in one season, despite the isolation and the flu vaccine.

This may be an unpopular question to ask now, but are we responding appropriately to the SARS-CoV-2, aka the coronavirus ?

As of 18:04 pm on 23/03/20, as per the website of the Ministry of Health, eight people have died in India from COVID-19 out of almost 400 confirmed cases. With our low testing levels, there very well could be more. Projecting what percentage of the population will be infected, and then extrapolating that to the number of deaths is always a tricky exercise. There have been statements that COVID-19 can infect up to 60 percent of the Indian population, in a worst-case scenario. This is somewhat like projecting revenue growth numbers in start-ups. And about just as useful.

As of 18:04 pm on 23/03/20, as per the website of the Ministry of Health, eight people have died in India from COVID-19 out of almost 400 confirmed cases. With our low testing levels, there very well could be more. Projecting what percentage of the population will be infected, and then extrapolating that to the number of deaths is always a tricky exercise. There have been statements that COVID-19 can infect up to 60 percent of the Indian population, in a worst-case scenario. This is somewhat like projecting revenue growth numbers in start-ups. And about just as useful.

And then there is Italy.

Yes, the situation in Italy is tragic and horrifying.

But India is not Italy.

What are the differences?

The age profile is probably the critical difference between India and Italy. One in every five Italians is over 65. Only about one in twenty Indians is over 65. This is meaningful, while America’s experience shows that people in their 30s and 40s are in the ICU because of COVID-19 , the population group most at risk for hospitalisations, ICU admissions and death, remains above 65 years of age.

The average temperature in Italy is in the early teens now. Last I checked, Lombardy was at 11°C. The temperature in Indian metros is double that, and in Tamil Nadu, three times that. Ambient temperature always plays a role in infections. It appears to do so in Dengue transmission, and may play a role here. That is why the seasonal flu gives way to the poxes and diarrhoea as summer rolls along. It is part of the seasonal cadence of infection. This could be one explanation of why colder countries are affected more, and warmer countries less. But we cannot be complacent – cases are rising, and other RNA virus pandemics have raged through summer months.

India does not have Italy’s (especially Northern Italy’s) medical infrastructure. Ours would fall to a lighter blow.

There are similarities too. We also love our Nani’s and our Paati’s, and we tend to be packed quite closely together.

To repeat, we cannot be complacent.

India’s handling of the crisis until now, barring testing, has been hard to fault. The hammer has been falling quite hard (recommended reading: The Hammer and the Dance). The travel restrictions, bringing back stranded overseas Indians back, even the Janata Curfew. Shutting down schools, cinema theatres, postponing exams. The article refers to the hammer as aggressive complete lockdown measures for weeks followed by a dance, with testing and tracking, until a vaccine is developed. By aggressively acting, the hope is for the spread to be curtailed (see figure)

Coronavirus Outbreak Aggressive testing containment in small pockets what India really needs to combat COVID19" width="825" height="292" />

The hammer fell harder as the number of cases ramped up. 75 districts, where a case of COVID-19 has been reported, have been shut down – meaning only essential services are allowed to function. Passenger trains, including metros and suburban trains, have been suspended. Moreover, interstate travel has been suspended, with the goal that travellers from metros don’t take the virus to rural India where the medical infrastructure cannot take the shock. As I write, Tamil Nadu, with nine confirmed cases in a 1,30,000+ square area, has announced Section 144.

The goal is the same: reduce contagion by lowering social contact, allowing hospital capacity to cope. Take Chennai, for example. As of 23/03, there were four confirmed cases in the city. Assume, worst-case, the ‘true’ number is ten times that, or 40 confirmed cases in the city. Now, let us use the reproduction number of 2.79 (this is the number the CDC came up with). This means each infected Chennaite would, in turn, infect 2.79 others. Extending this chain up to 31 March gives us,

Coronavirus Outbreak Aggressive testing containment in small pockets what India really needs to combat COVID19" width="825" height="294" />

The blue line means introducing social isolation measures, bringing the reproduction number to 1.5. Without it, Chennai may have had 14,000+ cases, with it, only 103 cases by 31 March. Chennai has 20,000 Hospital Beds, 1,200 ICU Beds, 250 of those with Ventilators (Source: Sam Mehta, Vice Chairman, Dr Mehta’s Hospitals).

Now, consider the situation, where the true number of cases is far higher, 10x, as one expert claimed. That means the true number of COVID-19 cases in Chennai on the 23 is 40. The disease spread would look like this —

Coronavirus Outbreak Aggressive testing containment in small pockets what India really needs to combat COVID19" width="825" height="291" />

Now, thanks to the CDC again, we have hospitalisation, ICU-admission and fatality rates by age group. We also have the age breakup of Chennai’s population. Putting these two together, with the data above, we get

Coronavirus Outbreak Aggressive testing containment in small pockets what India really needs to combat COVID19" width="825" height="301" />

Without lockdown, if the true number of cases was 10x what was reported, then, without lockdown, the ICU capacity would be overwhelmed, and we would have had above 1,300+ deaths more than with a lockdown in place.

Take, Mumbai, one of the epicentres of the COVID-19 epidemic in India. Mumbai had a cumulative total of 53 confirmed COVID-19 cases as of 23/03 (Source: Gayatri Nair Lobo, ATE Chandra Foundation). Projecting this forward to 31 March, we get this —

Coronavirus Outbreak Aggressive testing containment in small pockets what India really needs to combat COVID19" width="825" height="293" />

If we assume the true number of cases is 10x of 53 confirmed cases, that takes us to 530 cases as of 23/03/2020. Now, if we assume each infected person was to in turn infect 2.79 other persons, then we land up nearly two million infected persons in Mumbai by 31/03. A mind-boggling number. Most of those would still not require hospitalisation, and many will not even show symptoms. If we again assume that hospitalisation, ICU-admission and fatality rates by age group were similar to the US, then we get this —

Coronavirus Outbreak Aggressive testing containment in small pockets what India really needs to combat COVID19" width="825" height="302" />

It’s a no-brainer to take Mumbai into a lockdown.

Keep in mind for every Mumbai and Chennai, there is a Madurai with no reported cases (as of now). The logic of shutting down balancing saved lives vs shattered lives starts coming apart.

Because every action carries price tags – yes, that is plural. Each tag is paid by a different section of the population. Some people are relatively unaffected – they are well off, and can enjoy the lack of pollution and sound and traffic. Others are affected but manageably so – these are the information warriors who can work from home, using laptops.

Others have their income protected. Many corporates have come forward saying wages and jobs will be protected.

These jobs form but a few strands of India’s employment tapestry. Informal employment in India is vast – most of the workers managing your waste for you in Dharavi are informal. Many of them are migrants. Payments from the state are unlikely to reach them. Another vulnerable set is the millions of sex workers in India. “HIV can be stopped with condom use. But this [the coronavirus ] means no physical proximity – that message has gone out far and wide. Likely, very few clients will be going to them [the sex workers] now,” says Ashok Alexander, who earlier headed the Indian operations of Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, where he helped set up the world’s largest-ever privately sponsored HIV prevention program. “Sex work in India is largely invisible. It is a consumer product that has not been recognised as a profession. Which means there is little prospect of any support reaching these women. Many of these women have children dependent on them. Life, is often is about day-to-day survival.”

That survival is in question now.

Work-from-home is a cruel joke for those who work with their hands and bodies and for daily wages. The silence so many of us applaud as the streets turn empty is the sound of hunger in other people’s homes. And for many of those, neither the forbearance of their corporates nor dole-outs from governments, will reach and help. By shutting down indiscriminately, for the thousands we are hoping to save, are we choosing death-by-a-hundred cuts for thousands of others? State after state has begun implementing Section 144, whether it makes sense in the price-tag logic. Politically, it’s a no-brainer – your next-door neighbour has declared it. You don’t lose anything if you do – not now, when the whole population is held in fear-thrall. But, if you keep society and economy open, and people die, you become rich fodder for news channels and your political opponents. Competitive federal populism.

The more important consideration is if the lockdown is effective. A Janata curfew is rendered meaningless if people come together at five to celebrate together. No, the virus does not die in 12 hours. Italy declared a lockdown on 8/9 March. But, as per accounts, the lockdown came late, and was not strict enough: one account has over 50,000 people in Italy charged for breaking quarantine rules. With this kind of flouting, lockdowns are futile, worse, counter-productive – you pay the economic price, without reaping the safety gain. The hammer was more like a Shiatsu massage, and it did not work as planned. Sure enough, Italy called in the military to enforce the lockdown less than two weeks later. What matters is effective containment – size, as in many things, was not important.

This was the belief behind Singapore and South Korea approach.

They got an early start. Tested aggressively, and adopted different types of ‘hammers’ for different levels of exposure: positive cases, even cases without a single symptom, were held in hospitals, while those with exposure were asked to maintain strict home quarantine. The home quarantine included SMSs several times a day, which would verify location, and by spot checks. Singapore also ensured that business could stay open while following certain precautions: Each person entering a shop would have their temperature tested, and would note down their ID number, which helped in contact tracing. Any ‘cheating’ would be punished. For this approach to work, we need to start early (so all cases are caught), be disciplined (if only half the shops complied with the order, this wouldn’t work) and test aggressively.

In other words, Singapore and South Korea are following the needle approach — pin-pointed, intense action — rather than a broader hammer. And it appears to be working. Japan, where the outbreak appears to have been controlled, seems even more sanguine. A Japanese Health Ministry official was quoted as saying, “We don’t see a need to use all of our testing capacity, just because we have it. Neither do we think it’s necessary to test people just because they’re worried.”

What does this mean for India?

India (except perhaps Kerala) may have missed the early boat. On discipline, we have people actively flouting controls, with not enough punishment. And we have been held to not fare so well on testing. Most importantly, we do not have the capacity to ensure the curbs are held long enough.

Coronavirus Outbreak Aggressive testing containment in small pockets what India really needs to combat COVID19" width="825" height="428" />

Testing can be expensive. Two-part testing – with a cheaper screening test and a more expensive confirmatory test. The ICMR has recommended that the two tests should not cost more than Rs 4,500, with an appeal that they be free. Apart from availability, where the private labs will add capacity, there is accuracy. PCR’s need specialised technicians to run (yours truly has run PCR tests two decades ago, and know, from painful personal experience that they can be prone to error), there can be< contamination in sample collection leading to further error.

Then there are bottlenecks.

Dr Prabu Thiruppathy, Kois, a global healthcare investment firm (that has invested in molecular diagnostics across the world), says “The testing kits (PCR) need to be certified to be of acceptable accuracy by National institute of virology. Then these can be shipped and deployed at labs. However, protocol changes over the weekend mean that tests now need to be US FDA or European CE approved. A big problem is that the reagents seem to be still imported, although Indian companies make the final product in the country. Moreover, Gloves and masks are already in massive shortage across Indian hospitals.” Meaning there is a risk of contamination to the technicians collecting and testing the sample, is elevated.

One additional option is the just-approved testing in Cepheid machines, which require minimal human intervention and boast of a quick turnaround in a hospital setting.

What appears to balance out the need to overwhelm our health services, while not strangling the informal sector, is aggressive testing and containment in small pockets, with the help of private testing and, this is key, the army. We may not be able to do this effectively across 80 districts, but we can try to do this effectively in smaller pockets, where the number of cases is very high, relatively speaking. Maximise the safety bang for the economic buck. What India really needs, to use a term from another context, is a surgical strike – pointed, intense, effective. The hammer may cause more harm than the virus itself.

The writer is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, cleantech angel investor and author of The Climate Solution — India's Climate Crisis and What We Can Do About It published by Hachette. Follow her work on her website; on Twitter; or write to her at cc@climaction.net.

"Coronavirus Outbreak: How effectively will policies of travel restrictions and social distancing control the spread? "

Published : Mar 23, 2020

In the second of a four-part explainer on the coronavirus pandemic, Mridula Ramesh writes: if we spread to Stage 4, where we have epidemic local transmission of COVID-19, hospital capacities would soon be overwhelmed, which may leave millions dead. Which is why policy action has been aimed at ‘flattening the curve’ or spreading out the infection trajectory to allow hospitals to cope.

This is part 2 of an explainer on the coronavirus pandemic. In part 1, where did it come from? How does it spread? Who and how does it kill? What might stop it?,

***What are the implications of this on policy?

Pray for summer, obviously. But, what else?

Any policy has to be mindful of the virus, and of the capacity of the country.

Let us compare the treatment capability of different countries affected with India’s. This is data from the WHO, accessed through the World Bank.

Clearly, if we spread to Stage 4, where we have epidemic local transmission of COVID-19 , hospital capacities would soon be overwhelmed, which may leave millions dead. Which is why policy action has been aimed at ‘flattening the curve’ or spreading out the infection trajectory to allow hospitals to cope.

What has/can be done to prevent this?

Travel restrictions

The virus originated outside India. India reported its first confirmed COVID-19 case on 30 January 2020. Predictably, Kerala was the state who confirmed the case, given their excellent medical tracking abilities. The patient was a student who had been studying in Wuhan and returned to her home in Thrissur. In an interview, she is reported to have said,

“We left Wuhan by train to Kunming, took the flight to Kolkata and then to Kochi on 24 January. I had a phone message from the Indian embassy to report to the nearest medical hospital on arrival at Kochi airport, which I did. They took our temperatures and again there was no sign of any infection… I arrived in my village in Thrissur, I was careful to impose self-quarantine at home…On 27 January, I had a sore throat and cough for the first time and I immediately alerted the authorities and was asked to go the General Hospital in Thrissur. When I went there, I still did not have temperature and they started me on antibiotics… The result came in positive on 30 January, nearly a week after I left Wuhan.”

There were hundreds of Indian students studying in Wuhan. While others were later evacuated by the Indian government and quarantined, the first wave that came on their own presented a wider infection risk. While states like Kerala, with an excellent medical system, tracked and monitored the cases, what about those who returned to states with creakier infrastructure?

Within days of the first positive case being announced, the Indian government had announced a travel advisory, asking citizens to refrain from travelling to China, and saying anyone with a travel history to China from 15 January could be quarantined. They also stopped/cancelled visa facilities for Chinese nationals.

Italy also received its first COVID-19 courtesy Wuhan — in this case a Chinese couple who arrived from Wuhan on 23 January, and travelling through Italy. The Italian government sealed off the hotel, and suspended flights. Interestingly, on 31 January, the BBC reported the chief of the WHO, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, as saying, ‘there was no reason to limit trade or travel to China’.

Travel within India had not slowed. I was at a set of meetings in Delhi in early February. In the airport, only a handful of us were wearing masks. The pharmacy in the Delhi airport was still selling hand sanitisers at the regular price, though they did try to push the more expensive one first. The virus also spreads through the oral-faecal route. Given that so much of India’s drinking water is contaminated, this is of particular concern. If you want to look at it another way, this might help facilitate herd immunity.

For a while it seemed the virus might be contained. China had battened down the hatches, and was weathering the COVID-storm. The number of new cases globally was slowing down. The world heaved a sigh of relief. US President Donald Trump tweeted ‘The coronavirus is very much under control in the USA. … Stock market starting to look very good to me’

Meanwhile, in Italy, Iran and South Korea, the next phase of the epidemic was beginning.

In early March, the Indian government issued another travel advisory asking Indian citizens to refrain from travelling to Italy, Iran, South Korea and Japan, and suspending visas for citizens of those countries. In addition, all returning travellers would have to get a certificate of being COVID-free and self-declare that they were well. All travellers would be screened at the airport. Travel within India was still going on, but with some fear.

All around the world, travel restrictions were going up, and countries were sealing their borders. Even the Islamic State (ISIS) warned its terrorists not to enter Europe!

By 10 March, internal travel started to slow down, as the number of positive cases many of those either immediately returning from abroad or their family members/persons in close contact, began to ratchet upward.

There is a nifty little dashboard on COVID-19 timelines, which I would encourage you to check out. By taking the data from this dashboard week wise in March, I came up with this:

Clearly, the virus was being transmitted locally, through contacts with those that returned from foreign countries – Italy, the UK and the Middle East (Saudi Arabia, Iran and the UAE). The latest case, reported in Tamil Nadu, was different. This was 20-year old man who travelled by train from Delhi to Tamil Nadu, and as far as is known now, had not travelled abroad or come into contact with any foreign-returned person. Was this community transmission? It is far too early to say, especially given the low level of testing in India.

On 18 March, India banned passengers from Europe, the UK, Turkey, Afghanistan, Malaysia and the Philippines from entering the country. Furthermore, passengers who had travelled from COVID-19 hotspots, including Italy, from 15 February, would be quarantined for 14 days.

Passengers from UAE, Qatar, Oman and Kuwait would be placed under compulsory quarantine.

From the night of 22 March, India will shut off from the world. No commercial aircraft from a foreign country will be allowed to land in any Indian airport.

If implemented well, this could have a good effect. However, there are, how shall I put this politely, morons in our midst.

The Bengaluru newlywed techie’s wife’s story appears to have shades of grey, so let us leave that be. There is also the case of the Bengali bureaucrat’s son. Or the case of B-town singer, with some reporting that she hid in the bathroom to escape airport screening. It is confirmed that she was at parties with Members of Parliaments and senior politicians, putting the leadership of the country at risk. All three claim they were asymptomatic when they passed through airport screening.

The problem with self-declarations, even if people are truthful, and airport screenings is this: a significant number (between 17-30 percent) of people infected with the SARS-CoV-2 are asymptomatic. They have no fever, no cough, no sore throat. But they are infectious. They pass through every screen, and go on to infect those who may be less fortunate.

Imperfect as travel restrictions are, they are effective, and may have very well prevented from a full blown epidemic in India until now, when the temperatures are rising.

However, at the other end of the spectrum we have outright mal-intent. One example of this, are the kids partying in the beaches of Florida, who, on TV, say they don’t care about the coronavirus . Then there are those in India, who with full comprehension, of risks, take them anyway. Which is why we come to social distancing. Since anyone can have it, better to play it safe. The Prime Minister’s address to the nation on the 19 March said as much.

Social Distancing

Most countries are focussing on prevention, which in turn focusses on minimising the virus load transmitted from one person to another. At the centre of this effort is social distancing. In social distancing, we keep away from others, preferably at greater than one-metre distances, for as long as we can. The hope here is that by doing so we break the chain of spread of the virus.

Is it safe though? Is it realistic?

The virus is a tableau of unfairness. Those who brought it to India have enough money to travel by plane outside the country. This is a tiny fraction of India’s full population, many of whom have not travelled far away from their place of birth. Much of India is employed outside the formal sector, with their hands, where work-from-home is a cruel joke. Shutdowns affect those who, for no fault of their own, are impacted. I’m not saying shutdowns are a bad idea, but they come with a cost on those who cannot bear it.

Importantly, is social distancing realistic?

I recently walked through a part of Dharavi, one of the largest slums in Asia, which is a popular destination in the ‘poverty-tourism’ circuit. Houses, 8 feet by 5 feet, hold entire families while being stacked next and atop of other such houses. I was told that 70 percent, more than two-thirds, of Dharavi’s one million population relieves themselves in community toilets. During our walk, we did walk past two of these community toilets. They looked reasonably well maintained and had lines of men waiting, face down, lota in hand, for their turn.

Can we really believe that social-distancing is anything but a forlorn hope?

Where other options do we have? Shut down, test everyone, or weather the storm and hope for herd immunity. Let us consider each of them in turn next time.

The writer is the founder of the Sundaram Climate Institute, cleantech angel investor and author of The Climate Solution — India's Climate Crisis and What We Can Do About It published by Hachette. Follow her work on her website; on Twitter; or write to her at cc@climaction.net.

"Coronavirus Outbreak: From origin to spread, who it affects and the factors that may halt its progress — a primer"

Published : Mar 20, 2020

In the first of this four-part explainer, Mridula Ramesh answers essential questions about the coronavirus pandemic: Where did it come from? How does it spread? Who and how does it kill? What might stop it?

The Beginning

The Beginning

In November 2002, when the first atypical pneumonia case was reported in Guangdong, China, WeChat, China’s enormously popular social messaging app, was a dream. Those three months before the WHO office in Beijing received information about a ‘strange contagious disease’ that had left 100 people dead. The three months gave the deadly SARS-Co-V virus enough time to get a foothold and set off an epidemic that, within months, infected at least 8,000 people, killing 774 before dying out in the summer of 2003.

Seventeen years later, on 30 December 2019, Li Wenliang, a young ophthalmologist, shared that "seven cases of SARS confirmed" to his WeChat group, called ‘Wuhan University Clinical 04’. Within days, the Public Security Bureau in Wuhan called him in and got him to sign a statement saying he was lying and disturbing public order. What made Li a hero was he published the statement on Weibo. In January, Li took to Weibo again, saying,

‘I started having cough symptoms on 10 January, fever on 11 January and hospitalisation on 12 January’.

On 23 January, Wuhan, the epicentre of the epidemic shut down. There were far less than 700 publicly reported, confirmed cases of COVID-19 in China at that point of time. The truth is, China or the world did not know truly how many cases there really were. The world had never seen a quarantine of that scale — Wuhan alone had a population of 11 million. There were sporadic images coming through on the internet: people dying in the corridors of hospital, hospitals being overwhelmed. Doctors dying.

In February, Li gave his final social media update,

‘Today the nucleic acid test result is positive, the dust has settled and the diagnosis has finally been confirmed.’